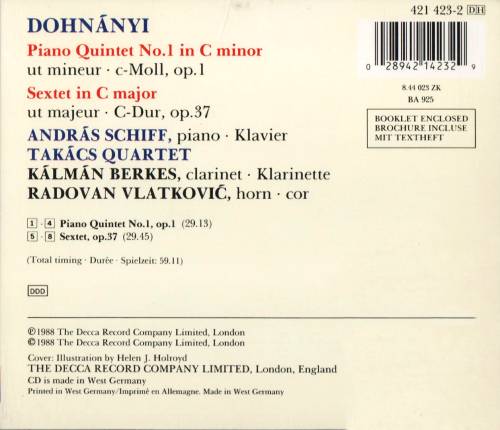

Ernst von Dohnányi (1877-1960)

1-4. Piano Quintet In C Minor, Op. 1 (29:13)

5-8. Sextet In C Major, Op. 37 (29:45)

Credits :

Piano – András Schiff

Clarinet – Kálmán Berkes

Horn – Radovan Vlatković

Ensemble – Takács Quartet :

Cello – András Fejér

Viola – Gábor Ormai

Violin – Gábor Takács-Nagy, Károly Schranz

15.6.25

DOHNÁNYI : Piano Quintet Nº. 1 · Sextet (András Schiff · Takács Quartet) (1988) Two Version | FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

15.8.24

DOHNÁNYI : Violin Concertos Nº 1 and 2 (Michel Ludwig · Royal Scottish National Orchestra · JoAnn Falletta) (2008) FLAC (tracks) lossless

Best known for his Variations on a Nursery Theme for piano and orchestra, the Hungarian composer Ernő Dohnányi also wrote two published Symphonies, two Piano Concertos and two Violin Concertos, all of which have been undeservedly neglected. The rarely heard Violin Concerto No. 1, notable for its Brahmsian slow movement, combines virtuosity and lyricism. Written in the mould of the great Romantic violin concerto, and with an unmistakably Hungarian flavour, the superbly orchestrated and remarkably inventive Violin Concerto No. 2 (1949-50) is worthy of being ranked alongside the Concertos by Barber and Korngold. naxos

Best known for his Variations on a Nursery Theme for piano and orchestra, the Hungarian composer Ernő Dohnányi also wrote two published Symphonies, two Piano Concertos and two Violin Concertos, all of which have been undeservedly neglected. The rarely heard Violin Concerto No. 1, notable for its Brahmsian slow movement, combines virtuosity and lyricism. Written in the mould of the great Romantic violin concerto, and with an unmistakably Hungarian flavour, the superbly orchestrated and remarkably inventive Violin Concerto No. 2 (1949-50) is worthy of being ranked alongside the Concertos by Barber and Korngold. naxos

Tracklist & Credits :

11.2.22

DOHNÁNYI : Piano Quintets (Schubert Ensemble of London) (1995) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The Serenade in C for string trio falls within the direct lineage of models in the genre by Mozart and Beethoven, yet proves a decisive watershed for Dohnányi himself, fully articulating his nationally infused mature style for the first time. The Piano Quintets reflect an enduring and deep-rooted regard for both Brahms and Schumann, and even Mendelssohn. Hyperion

DOHNÁNYI : String Quartet, Serenade & Sextet (The Nash Ensemble) (2018) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The music of Dohnányi (admired by figures as disparate as Brahms and Bartók) embodies virtues of taste, humour, impeccable control of form and beauty of style; all qualities relished by The Nash Ensemble in wonderful new recordings which can only assist with this composer’s continuing rehabilitation. Hyperion

16.1.22

DOHNÁNYI : Piano Concerto No 1 In E Minor • Piano Concerto No 2 In B Minor (Martin Roscoe · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Fedor Glushchenko) (1993) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 6 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The name of Ernest Dohnányi (born Hungary, 1877, died USA, 1960) hardly rings a bell today except in Hungary. Even those who remember him are likely to be familiar with only one of his works, his Variations on a Nursery Song for piano and orchestra (1914). His stage works, orchestral compositions including symphonies, concerti etc., vocal compositions such as the Stabat Mater (1953), as well as his numerous chamber music and piano compositions are now seldom played. One would search long to find his music in any concert programme. Yet at his peak he was one of the most versatile and influential musicians of his time. His youthful Piano Quintet (1895) was so highly esteemed by Brahms at its first performance that he personally made arrangements for it to be performed in the Vienna Tonkünstlerverein.

The name of Ernest Dohnányi (born Hungary, 1877, died USA, 1960) hardly rings a bell today except in Hungary. Even those who remember him are likely to be familiar with only one of his works, his Variations on a Nursery Song for piano and orchestra (1914). His stage works, orchestral compositions including symphonies, concerti etc., vocal compositions such as the Stabat Mater (1953), as well as his numerous chamber music and piano compositions are now seldom played. One would search long to find his music in any concert programme. Yet at his peak he was one of the most versatile and influential musicians of his time. His youthful Piano Quintet (1895) was so highly esteemed by Brahms at its first performance that he personally made arrangements for it to be performed in the Vienna Tonkünstlerverein.

It was his cellist father and Károly Förstner, a cathedral organist, who gave Dohnányi his first lessons in piano and theory. Having completed his secondary education he went to Budapest from his native town Pozsony (now Bratislava) in order to study at the Budapest Academy. (His school friend Béla Bartók followed suit.) There he studied piano with Thomán and composition with Koessler. After receiving his diploma in 1897 he spent the summer of the same year with composer and pianist Eugen d’Albert (Glasgow-born but of German-French-Italian origins) to whom, in 1898, Dohnányi eventually dedicated his First Piano Concerto, a work which received the Bösendorfer Prize.

It was in 1898 that Hans Richter, one of the leading conductors of the time, asked Dohnányi to join him in London as the soloist in Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. This tour, during which he gave 32 concerts in two months, established him as a concert pianist of the first rank. His interpretative power in the Austro-German classics, above all Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, as well as his dedicated involvement in chamber music playing, made him one of the most sought-after performers of his time. His pianistic ability combined with improvisational panache was such that when later his memory deserted him from time to time it was a popular pleasure among connoisseurs to hear how he wriggled out of trouble by stylishly improvising passages that led back to the original notes. It was Richter, too, who in 1902 introduced Dohnányi’s Symphony No 1 in D minor, in Manchester.

The great violinist Joachim, friend of Brahms, was also friend to Dohnányi whom he invited to Berlin where the composer was offered a professorship at the Hochshule in 1905. Ten years there were paralleled and followed by various prestigious appointments not only at the Budapest Academy but also as chief conductor of the Philharmonic Orchestra, a position which he held for the best part of 25 years from 1919. In 1931 he became the musical director of Hungarian Radio where he worked until 1944. With all these involvements he found time not only for composition but also for selecting concert repertoire with the aim of raising musical standards in Hungary. He gave as many as 120 performances there in one year. No wonder that Bartók saw in him a leading provider of Hungarian musical life. For four decades Dohnányi dominated the musical scene in his home country and beyond. It is to Dohnányi’s credit that although his musical temperament and outlook were very different from Bartók’s and Kodály’s he put his phenomenal performing ability to their service. In fact he recognised Bartók’s genius well before others and gave him practical support while his own countrymen were predominantly hostile. His long-standing relationship with America made him a welcome refugee when, after a few years stay in Austria (1944-1948), he decided to leave Europe for the New World. There he indefatigably continued his musical activities, not only in his capacity as pianist/composer-in- residence at Florida State University, but also as a touring performer. One of his last concerts was in 1956 at the Edinburgh Festival. Working to the very end of his life, he died during a recording session at the age of 83.

In this series featuring ‘The Romantic Piano Concerto’, Dohnányi’s two works in this form are fitting examples of the genre because he was throughout his life a romantic both at heart and in his musical language. Although he died as late as 1960 he had little to do with the musical developments of the twentieth century. The two Concertos on this recording evoke a world which belongs to the nineteenth century. Dohnányi continued to compose in a style deeply rooted in the Austro-German classical tradition exemplified by Brahms. His merit as a composer is that he was able to prolong meaningfully the classico/romantic past, of which he was one of the last practitioners, well into this century, both in his chamber and orchestral music. This he did with elegance, wit, and stylish virtuosity. The two Piano Concertos are fine examples of his fluent mastery of form and instrumentation.

The Piano Concerto No 1 in E minor, from the years of 1897–8, follows the traditional three-movement structure: fast-slow-fast. However, the first movement Allegro is preceded by an introductory ‘Adagio maestoso’ whose main theme is picked up, albeit in a modified way, by the first Allegro subject proper. It is characterised by a diminished 5th drop resolving upwards a minor second (E-A#-B). The structural importance of the introductory Adagio maestoso gains marked significance as it is reiterated at the end of the movement. There is nothing in the musical language—that is, in the rhythm, melody, harmony and musical structure as well as in the traditional orchestration—which Brahms would have found unfamiliar.

The second movement, with its largely pizzicato orchestral accompaniment, is in A minor. Its melodic contour is also derived in a subtle way from the ‘Adagio maestoso’. The last twenty-eight bars, during which the piano plays the opening theme originally introduced by the orchestra with broad arpeggio chords finally establishing the key of A major (known as ‘tierce de Picardi’), is an old trick, but it works superbly.

The third movement, Vivace, brings to its dramatic conclusion the opening Adagio maestoso theme which, motto-like, gives unity to the whole composition. Of the three movements this is perhaps the most Brahmsian in style with its lush sixths and thirds. A chorale-like theme played by the orchestra interrupts the flow of the cadenza. Then a frenetic coda in 6/8 is approached via a series of trills. Finally the time signature changes again, now to 2/4 Presto, leading the composition to its conclusion—not in E minor, but in the triumphant E major.

The Piano Concerto No 2 in B minor belongs to the post-World War II years, 1946–7. Thus nearly fifty years separate the two Concertos on this CD. The composer’s compositional style, however, shows little change. It is amazing to think that Bartók’s Third Piano Concerto was written two years before this one. The first Allegro movement of this Concerto also opens with a quasi-motto theme. There is something Hungarian to it both melodically and rhythmically. Among several striking passages the one which stands out is the ‘Poco meno mosso’ entry of a theme which more or less dominates the second half of the movement.

The second movement, ‘Adagio poco rubato’, again evokes Hungarian, or rather a stylised Hungarian gipsy style in G minor. It ends in G major with a gradually speeded-up repetition of the note G in the orchestra, leading directly without a break to the third movement, Allegro vivace. The ostinato G is spiced by a minor second clash which gives backing to the entry of the energetic main theme. The motto theme of the first movement reappears, albeit en passant, over a long held E in the bass. This gives way to a spirited unfolding of the material and the eventual conclusion of the Concerto.

It is incorrect to suggest, as some do, that Dohnányi bridged the gap in Hungarian music between Liszt and Bartók. This is not so, since he did not share their innovating and pioneering compositional genius. He got stuck in a style somewhere between Brahms and Saint-Saëns. What he offers, however, is an unfailing romantic spirit which to this day can evoke the musical values of yesterday, which he served and defended with such inspired dedication. Hyperion

Ernő Dohnányi (1877-1960)

Piano Concerto No 1 in E minor Op 5 [44'56]

Piano Concerto No 2 in B minor Op 42 [29'44]

Conductor – Fedor Glushchenko

Leader [Orchestra] – Geoffrey Trabichoff

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Photography By [Martin Roscoe] – Paul Deaville

Piano – Martin Roscoe

30.12.20

DOHNÁNYI, JANÁCEK : Violin Sonatas (Shaham-Erez) (2009) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

29.12.20

28.12.20

21.8.20

MARTINU • KODÁLY • DOHNÁNYI • JOACHIM • ENESCU : Music for Viola and Piano (Bradley-Hewitt) (2011) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

From the end of the 19th century and onward, the frequency with which prominent composers were found writing for the viola increased dramatically. This phenomenon was seen around the world as the instrument's deep, resonate sound fell more into favor and virtuosos became more commonplace. This Naxos album focuses on viola works to emerge from Hungary. From this country, composers often fell into two camps. The first were those who adopted the popular late-Romantic, German idiom; here, this is represented by the Joachim Op. 9 Hebrew Melodies and the Dohnányi Op. 21 Sonata in an arrangement by performer Sarah-Jane Bradley. (Dohnányi himself had played an arrangement of the piece with violist Lionel Tertis). Countering these highly lyrical compositions are those from composers who sought to develop a more nationalistic musical idiom and include the Martinu Sonata, H. 355, the Kodály Adagio, and the Enescu Concertstück. Bradley's program is not only well thought out and diverse, but demonstrates the viola's abilities both as a virtuosic instrument and one capable of delivering beautiful melodic lines. Joined by pianist Anthony Hewitt, Bradley's performances are admirable in many respects. Her playing is very calm and restrained; there are no moments when listeners are left gasping for air as the violist strains for large shifts or to make it to the end of difficult passagework. Her intonation is generally solid, her tone is warm and even across the range of her instrument. On the downside, her sound is not exceptionally big. Hewitt's playing is quite accommodating in this respect so the piano never actually obscures Bradley's playing, but there is a notable lack of any big, forte sound, or a wide dynamic range. by Mike D. Brownell

From the end of the 19th century and onward, the frequency with which prominent composers were found writing for the viola increased dramatically. This phenomenon was seen around the world as the instrument's deep, resonate sound fell more into favor and virtuosos became more commonplace. This Naxos album focuses on viola works to emerge from Hungary. From this country, composers often fell into two camps. The first were those who adopted the popular late-Romantic, German idiom; here, this is represented by the Joachim Op. 9 Hebrew Melodies and the Dohnányi Op. 21 Sonata in an arrangement by performer Sarah-Jane Bradley. (Dohnányi himself had played an arrangement of the piece with violist Lionel Tertis). Countering these highly lyrical compositions are those from composers who sought to develop a more nationalistic musical idiom and include the Martinu Sonata, H. 355, the Kodály Adagio, and the Enescu Concertstück. Bradley's program is not only well thought out and diverse, but demonstrates the viola's abilities both as a virtuosic instrument and one capable of delivering beautiful melodic lines. Joined by pianist Anthony Hewitt, Bradley's performances are admirable in many respects. Her playing is very calm and restrained; there are no moments when listeners are left gasping for air as the violist strains for large shifts or to make it to the end of difficult passagework. Her intonation is generally solid, her tone is warm and even across the range of her instrument. On the downside, her sound is not exceptionally big. Hewitt's playing is quite accommodating in this respect so the piano never actually obscures Bradley's playing, but there is a notable lack of any big, forte sound, or a wide dynamic range. by Mike D. Brownell

10.12.19

19.10.19

ERNÖ DOHNÁNYI : The Complete Solo Piano Music, Vol. 1 (Martin Roscoe) (2011) FLAC (tracks), lossless

ERNÖ DOHNÁNYI : The Complete Solo Piano Music, Vol. 2 (Martin Roscoe) (2011) FLAC (tracks), lossless

ERNÖ DOHNÁNYI : The Complete Solo Piano Music, Vol. 4 (Martin Roscoe) (2018) FLAC (tracks), lossless

ERNÖ DOHNÁNYI : The Complete Solo Piano Music, Vol. 3 (Martin Roscoe) (2015) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

+ last month

MARTHA COPELAND — Complete Recorded Works In Chronological Order Volume 2 · 1927-1928 + IRENE SCRUGGS — The Remaining Titles 1926-1930 | DOCD-5373 (1995) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

One of many early blues and jazz women who were overshadowed and ultimately eclipsed by Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, and Bessie Smith, Martha Co...

.jpg)

.jpg)