Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–1845) was a genius of quite extraordinary dimensions. He had reached full maturity as a composer by the age of sixteen (1825, the year of the String Octet), by which time he had also proved himself a double prodigy on both piano and violin, an exceptional athlete (and a particularly strong swimmer), a talented poet (Goethe was a childhood friend and confidante), multi-linguist, water-colourist, and philosopher. He excelled at virtually anything which could hold his attention for long enough, although it was music which above all activated his creative imagination.

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–1845) was a genius of quite extraordinary dimensions. He had reached full maturity as a composer by the age of sixteen (1825, the year of the String Octet), by which time he had also proved himself a double prodigy on both piano and violin, an exceptional athlete (and a particularly strong swimmer), a talented poet (Goethe was a childhood friend and confidante), multi-linguist, water-colourist, and philosopher. He excelled at virtually anything which could hold his attention for long enough, although it was music which above all activated his creative imagination.

Mendelssohn was an exceptionally gifted pianist, whose early studies under Ludwig Berger progressed at an astonishing rate. After hearing a recital given at home by the twelve-year-old boy, Goethe exclaimed: ‘What this little man is capable of in terms of improvisation and sight-reading is simply prodigious. I would have not thought it possible at such an age.’ When a companion reminded him that he had heard Mozart extemporize at a similar age, the great poet replied: ‘Just so!’ This was in 1821, by which time Mendelssohn had already composed a violin sonata, three piano sonatas, and two operas!

Mendelssohn’s mature piano style was derived not so much from the orchestral texturing of Beethoven and Schubert, as from the filigree intricacies of the German virtuoso piano school, represented principally by Hummel and Weber, further enhanced by a Mozartian emphasis on textural clarity. It was never Mendelssohn’s intention to push contemporary keyboard instruments beyond that of which they were comfortably capable, more to utilize those qualities for which they were best adapted—brilliant clarity in the treble register, and the ability to sustain a flowing, cantabile melody without undue bass resonance.

Mendelssohn’s first surviving works in concerto form date from 1822: the D minor Violin Concerto (not the popular E minor, a much later composition) and the Piano Concerto in A minor, both with string orchestra accompaniment, closely followed by a D minor Concerto for violin, piano and strings in May 1823. The Concertos for two pianos also belong to this early group, the E major being dated 17 October 1823, and the A flat major 12 November 1824. Both works had entirely dropped out of the repertoire until, in 1950, the original manuscripts were ‘rediscovered’ in the Berlin State Library.

Mendelssohn’s sister, Fanny, was also a gifted pianist, and it is almost certain that the E major Concerto was written with her in mind. However, it also appears likely that the A flat Concerto was inspired by Felix’s first encounter with the young piano virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles. Upon seeing the boy Mendelssohn play, even Moscheles could barely believe his eyes: ‘Felix, a mere boy of fifteen, is a phenomenon. What are all other prodigies compared with him?—mere gifted children. I had to play a good deal, when all I really wanted to do was to hear him and look at his compositions.’

The major criticism levelled at the Two-Piano Concertos is their tendency to overstretch relatively fragile musical material, as, with two soloists to contend with, Mendelssohn had been keen to ensure that the music was shared equally, thus involving an unusual amount of repetition. It would hardly be fair to expect even Mendelssohn to have achieved the miraculous thematic concision and structural cohesion of the E minor Violin Concerto and G and D minor Piano Concertos at such an early age.

The opening tutti of the E major Concerto uncovers a vein of dream-like contentment which was to become Mendelssohn’s expressive trademark. Virtually every subsequent composition contains passages of this nature contrasted, as here, by fleet-footed music of quicksilver brilliance. Even the use of Mozartian falling chromaticisms fails to cloud the blissfully trouble-free outlook.

The central 6/8 Adagio anticipates Mendelssohn’s favourite arioso Lieder ohne Worte style, whilst the high velocity finale demonstrates the composer’s precocious ability to assimilate Hummelian semiquaver athletics, and organize them into a convincing (if not yet fully developed) structure, transcending the aimless note-spinning of many of his older contemporaries.

The first movement of the A flat major Two-Piano Concerto is Mendelssohn’s longest concerto movement, and despite the composer’s declared preference for the E major Concerto, it displays a greater awareness of internal balance and structural proportions than its younger companion. The Mozartian opening theme (shades of the A major Concerto K414!) is embellished by some decidedly un-Mozartian virtuoso cascades during the soloists’ exposition, although a second lyrical idea is decidedly more restrained in its pyrotechnical aspirations.

The wistful Andante is clearly premonitory of the main theme of the G minor Piano Concerto’s slow movement, even if the continually flowing 6/8 metre and self-conscious virtuoso flourishes betray a certain lack of formal confidence in comparison with the later work.

Weber clearly marks the starting point for the good-natured Allegro vivace finale, its jocular high spirits being effectively contained by passing moments of mild contrapuntal ingenuity. The exuberant coda forces the main theme into overdrive, betraying a refreshingly boyish naivety, in stark contrast to the startling individuality and resourcefulness of the work as a whole. At only fifteen yeary of age, Mendelssohn was no mere fledgling composer but a highly creative intelligence on the verge of artistic maturity. Hyperion

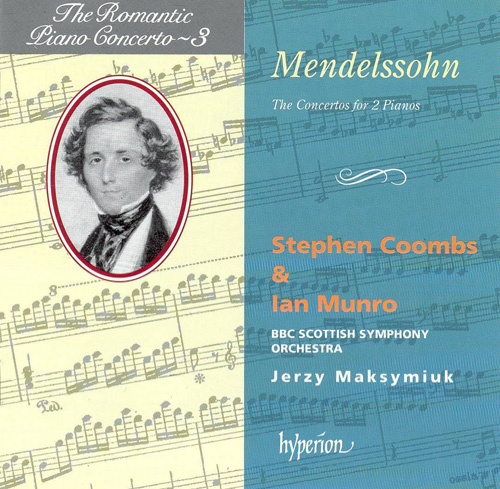

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Concerto for two pianos in A flat major[41'28]

Concerto for two pianos in E major[30'35]

Credits :

Conductor – Jerzy Maksymiuk

Leader – Geoffrey Trabichoff

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Ian Munro, Stephen Coombs

.jpg)