FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

1-4. String Quartet No. 1 In G Minor (1818) (32:30)

5-8. String Quartet No. 2 In A Minor (1849) (21:37)

9-13. String Quartet No. 3 In E Flat Major (1849) (21:47)

Ensemble – The Yggdrasil Quartet

Cello – Per Nyström

Viola – Robert Westlund

Violin [II] – Per Öman

Violin [I] – Fredrik Paulsson

4.2.26

FRANZ BERWALD : The Complete String Quartets (The Yggdrasil Quartet) (1996) FLAC (tracks), lossless

11.2.22

ROMANTIC ENSEMBLES — Septets, Octets & Nonets of : SPOHR · HUMMEL · BERWALD · KREUTZER · BEETHOVEN & SCHUBERT (2006) 6CD BOX-SET | Two Version | FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

One of the reasons this modest and innocuous-looking box is so desirable is the performances included. These are not just any groups performing these works, but top-flight ensembles -- The Berlin Philharmonic Octet, the Wiener Kammerensemble, and Britain's the Nash Ensemble. The reason that this can be marketed so cheaply is that all are older recordings, but most are at least digital and the performances are all first-rate. Brilliant Classics' Romantic Ensembles would make a lovely gift for a wind player, or someone specifically interested in wind ensemble music, and the modest asking price won't break the bank. Uncle Dave Lewis

CD1 :

SPOHR

Nonet in F major Op. 31

Octet in E major Op. 32

CD2 :

HUMMEL

Septet (The Military) in C major Op. 114

KREUTZER

Grand Septet in E flat major Op.62

CD3 :

HUMMEL

Septet in D minor Op. 74

BERWALD

Grans Septet in B flat major

CD4 :

SPOHR

Septet in F major Op. 147

Quintet inh C minor Op. 52

CD5 :

SCHUBERT

Octet in F major D8003, Op. 166

CD6 :

BEETHOVEN

Septet in E flat major Op. 20

Septet in E flat major Op. 81b

Credits :

CD1 - CD4

The Nash Ensemble

CD5

Berlin Philarmonic Octet

CD6

Wiener Kammerensemble

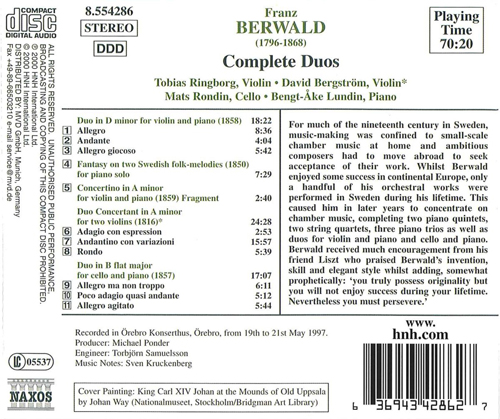

FRANZ BERWALD : Complete Duos (Bergstrom, Lundin, Ringborg, Rondin) (2000) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Complete Duos

Almost everybody would agree that Franz Berwald was the musical world's leading light in nineteenth-century Sweden. Many regard him as Sweden's foremost composer ever. But during his lifetime few of his countrymen appreciated his art.

This was partly because symphonies, the genre at which he excelled, were little appreciated. Besides operas and Singspiele, more intimate forms of music practised in the home with friends were preferred, such as piano pieces, chamber music, works for male choir and solo songs. Most of what was written was unpretentious in the salon music vein.

Orchestral concerts were given sporadically by the Hovkopellet, the orchestra of the Royal Opera, but the few symphonies that were presented in these concerts were foreign and usually quite old. For decades in Sweden no new symphonies appeared; Adolf Lindblad's Symphony No. 1 being the only example. Its first performance in 1832 is significant from a musical historical point of view, but it hardly made an impact. Around ten years later the Leipzig Gewandhaus-orchester played it, but in Sweden Lindblad remained known exclusively for his songs and chamber music.

It is therefore easy to understand why Berwald the sophisticate found the antiquated Swedish music scene suffocating. In 1829, at the age of thirty-three, he left Sweden and moved to Berlin, where he remained for twelve years, working not as a musician but in one of the other professions he was obliged to practise during his lifetime in order to support himself. As a skilled orthopedic surgeon he managed to make a successful living, from 1835 running his own orthopedic institute. In his free time he wrote a not insubstantial amount of music, first and foremost operatic fragments, although nothing complete has emerged from this time. One can wonder why, when he had now found a more inspiring milieu.

In the spring of 1841 he closed the institute and moved to Vienna, it seems to continue his work in the orthopedic field. He discovered, however, that the Viennese showed an interest in his music, which seems to have cleared his writers' block. Although he only remained in Vienna for a year he managed to write several works, including two symphonies, four orchestral fantasies and the opera Estrella de Soria. Some of the works were played immediately, including most of the opera. He himself conducted three of the shorter pieces. The reception he received in this cosmopolitan city was more positive than any he had experienced before. One can understand why he might feel that the world was ready for his music, even Sweden. After thirteen years abroad he decided to return home. In April 1842 he arrived in Stockholm with his bags full of new music.

His hopes had been in vain however. The Swedish music scene had not changed noticeably at all. Stockholm, was, apart from the Opera, as provincial as it had always been, at least it seemed that way to Berwald who was now used to the rich concert life on the continent. The few compositions he did manage to have performed met with little success. Some works were deemed to be uninteresting, others the work of an eccentric outsider. Yet he did have some new ideas – from a Swedish perspective. Inspiration came from innovators such as Beethoven and Cherubini and, to a certain extent, Weber. When it came to inventiveness, sudden leaps and unexpected key changes he often went further than they did. The musical development of a piece by Berwald was far less predictable than most of the music that was known in Sweden at the time, and for us it is precisely the unexpected which makes it so exciting.

During his years abroad Berwald must have heard the music of Europe's true innovators; Berlioz, Liszt and Wagner, however their influence is noticeably absent from his music. He continued to draw inspiration from the classicists and early romantics, Gluck and Mozart being among those he admired. What was foreign to Swedish audiences of the day was his pronounced personal style, rather than anything truly revolutionary.

Of Berwald's four symphonies, only the Sinfonie sérieuse (Naxos 8.553051) was played during his lifetime; once, badly rehearsed and with a greatly reduced orchestra. The performance took place at the Royal Opera House in Stockholm in 1843 under the direction of a conductor who, it seems, showed no great interest in the work. This was Berwald's cousin Johan Fredrik Berwald, renowned as an imaginative director of music, but not on very good terms with cousin Franz, ten years his junior.

Whether through personal animosity, a lack of understanding of the music or quite simply insufficient rehearsal time, Swedish audiences' only opportunity to hear the symphonic genius of Berwald was thus lost. The work was not performed again until 1876, eight years after Berwald's death. Several of the other symphonies had to wait until the beginning of the twentieth century for first performances.

In 1846 Berwald departed once more for foreign shores, stopping in Paris, Vienna, Salzburg and southern Germany. In Vienna he was once again warmly received, on one occasion in a performance with Jenny Lind. In Salzburg he became one of the few Swedes to have the rare honour of being elected an honorary member of the Mozarteum. He was also accorded warm receptions elsewhere.

Economic difficulties forced Berwald to return to Sweden for good in 1849 and for seven years he managed a glassworks in Ångermanland in Northern Sweden. He was still able to spend his winters in Stockholm where, amongst other things, he was able to take part in performances of chamber music in the homes of various musically-minded families. His failure to gain an audience for his larger works caused him now to concentrate almost completely on chamber music. In the ten years after his return to Sweden he completed two piano quintets, two string quartets, three piano trios as well as duos for violin and piano and cello and piano. Six of these works he had published by the Hamburg publishing house Schuberth.

It is to this period that four of the works on the present recording belong. The remaining piece appears to have been written in 1816 or 1817 by a twenty-year old Berwald who had already been employed by the Hovkapellet for four years. His younger brother August was also employed there and from time to time the two violinists gave concerts in Stockholm and elsewhere. The Duo Concertant for two violins may have been composed for just such an occasion. That the piece survives at all today is pure chance; in 1931 a man by the name of Martin Andréason was walking past a demolition site when he noticed a few sheets of manuscript sticking out of an abandoned suitcase amongst the rubble. Fortunately the man was not just anyone, but one of the repetiteurs at the Royal Opera in Stockholm. When he opened the case he discovered a bundle of old manuscripts including the Duo Concertant. A further coincidence was that Andréason's wife was the violinist Lottie Andréason, who for many years had been a member of the Berwald Trio together with the composer's grand-daughter, the pianist Astrid Berwald. It was natural that Lottie therefore be entrusted with the manuscripts. It transpired that they had been given to Henrik Hästesko, a violin pupil of Berwald's cousin Johan Fredrik Berwald, and that they had remained in the Hästesko family until they were discovered in the abandoned suitcase.

The Duo for cello (or violin) and piano seems to have been written in the early autumn of 1857, when Berwald had just returned from a visit to Weimar, during which he received praise from Liszt for some of his works. Berwald dedicated the Duo to a cellist from Weimar, Bernhard Cossman, who gave the first performance of the work in January 1859.

In June of that year the work received a successful performance in Leipzig from Friedrich Grützmacher (best known today for his dubious edition of one of Boccherini's cello concertos) and the twenty-one-year old pianist Hilda Thegerström, a protogée of Berwald's whom he introduced to Liszt. Following an acclaimed début that year Thegerström soon came to be regarded as Sweden's finest pianist.

At some point between 1858 and 1860 Berwald wrote the Duo for violin and piano. No performances during Berwald's lifetime are documented, but it may well have received a private performance at the home of Berwald's friend Lars Fries, where many of Berwald's works had received their first airings. In any case the manuscript was in the possession of Fries at the time of the composer's death.

The violin part of the Concertino for violin and piano was written for a musician who was to become world-famous; the soprano Christina Nilsson (1843-1921), who, as a child was well-known enough in the dance halls of her home province of Småland to be given the nickname Stina from Snugge. In 1859 she began lessons with Berwald, who offered her lodgings in his home. At various song recitals in Stockholm the following year she delighted audiences with her violin playing as well as her singing, presumably including her teacher's Concertino. Only the first part survives today, and it is not known how much longer the piece originally was. In contrast to the brilliant piano parts of the completed duos the piano part here appears purely in a supporting role.

Apart from his Piano Concerto for Hilda Thegerström (Naxos 8.553052), Berwald did not attempt any larger scale works for the piano, although several smaller pieces of various types exist. The Fantasy on two Swedish folk-melodies has been preserved only in an anonymous manuscript in a hand other than Berwald's, and although it does not name him it has been attributed to Berwald. Probably written in the late 1850s it contains the Värmlandsvisan (‘Värmland Song’), well-known in Sweden to this day, and a melody that is believed to be derived from a polka by the Dalecarlian fiddler Pekkos Per. by Sven Kruckenberg (English version: Andrew Smith)

FRANZ BERWALD : Pianotrio Ess-dur & d-moll Pianokvintett c-moll (1989) Two Version | FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

1-2. Piano Trio D-moll (Trio No. 3 D Minor) (24:15)

3. Pianokvintett C-moll (Piano Quintet C Minor) 23:28

4-6. Piano Trio Ess-dur (Trio No. 1 E. Flat Major) (19:20)

Credits :

Cello – Ola Karlsson

Orchestra – Berwaldkvartetten

Piano – Lucia Negro, Stefan Lindgren

Violin – Bernt Lysell

BERWALD : Piano Trios Nºs 1-3 (Ilona Prunyi · András Kiss · Csaba Onczay) (1993) Two Version | FLAC (image+tracks+.cue), lossless

For much of the nineteenth century in Sweden, music-making was confined to small-scale chamber music at home and ambitious composers had to move abroad to seek acceptance of their work. Whilst Berwald enjoyed some success in continental Europe, only a handful of his orchestral works were performed in Sweden during his lifetime. This caused him in later years to concentrate on chamber music, completing two piano quintets, three string quartets, four piano trios as well as duos for violin and piano and cello and piano. Berwald received much encouragement from his friend Liszt who praised Berwald’s invention, skill and elegant style whilst adding, somewhat prophetically: ‘you truly possess originality but you will not enjoy success during your lifetime. Nevertheless you must persevere.’naxos

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

1-3. Piano Trio No. 1 In E Flat Major

4-6. Piano Trio No. 2 In F Minor

7-9. Piano Trio No. 3 In D Minor

Credits :

Cello – Csaba Onczay

Piano – Ilona Prunyi

Violin – András Kiss

BERWALD : Piano Trios Vol. 2 (Kálmán Dráfi · György Kertész · Jozsef Modrian) (1993) Two Version | FLAC (image+tracks+.cue), lossless

The Swedish composer Berwald found more welcome at home for his chamber music than for his larger scale compositions, in spite of his success abroad. This, the second volume of his Piano Trios, includes two of the five that he completed and fragments of two other unfinished works.naxos

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

1-3. Piano Trio In C Major (1845) (26:52)

4. Piano Trio In E Flat Major (Fragment) 10:31

5. Piano Trio In C Major (Fragment) 7:20

6. Piano Trio No. 4 In C Major 18:46

Credits :

Performer, Cello – Kertész György

Performer, Piano – Dráfi Kálmán

Performer, Violin – Jozsef Modrian

Painting [View of Lidingobro] – Carl Wilhelm Wilhelmson

Photography By [Photo of Painting] – Connaught Brown, London, UK, Bridgeman Art Library

FRANZ BERWALD : Complete Piano Quintets (Uppsala Chamber Soloists · Bengt-Åke Lundin) (2000) Two Version | FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

For much of the nineteenth century in Sweden, music-making was confined to small-scale chamber music at home and ambitious composers had to move abroad to seek acceptance of their work. Whilst Berwald enjoyed some success in continental Europe, only a handful of his orchestral works were performed in Sweden during his lifetime. This caused him in later years to concentrate on chamber music, completing two piano quintets, two string quartets, three piano trios as well as duos for violin and piano and cello and piano. Berwald received much encouragement from his friend Liszt for his piano quintets, and dedicated his Quintet in A major to Liszt, a ‘true poetic master’. When Liszt received a score of the work he praised Berwald’s invention, skill and elegant style whilst adding, somewhat prophetically: ‘you truly possess originality but you will not enjoy success during your lifetime. Nevertheless you must persevere. naxos

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

1-3. Piano Quintet No. 1 In C Minor (25:31)

4-7. Piano Quintet No. 2 In A Major (31:48)

8-9. Two Movements From A Piano Quintet In A Major (5:31)

Credits :

Orchestra – Uppsala Chamber Soloists

Piano – Bengt-Åke Lundin

Cover [painting] – Walter Moras

FRANZ BERWALD : Symphonies and Overtures (SRSO · Roy Goodman) 2CD (2004) Serie Dyad | Two Version | FLAC (image+tracks+.cue), lossless

This set contains the four complete surviving symphonies, the fragmentary youthful A major Symphony (completed for this recording by Duncan Druce), and overtures to two of the composer's most successful operas.

There could be no orchestra more qualified to record the works of Berwald than that of the Swedish Broadcasting Corporation. Here they are conducted by Roy Goodman and recorded in the Berwald Hall in Stockholm. Hyperion

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

Tracklist 1 :

1. Overture To Estrella De Soria (1841) 7:56

2-4. Sinfonie Singulière (Symphony No.3 In C Minor) (1845) (27:53)

5. Overture To The Queen Of Golconda (1864) 7:41

6-8. Sinfonie Capricieuse (Symphony No.2 In D Major) (1842) (27:20)

Tracklist 2 :

1. Symphony In A Major, Fragment (1820)

(Edited By [Completed By] – Duncan Druce)

2-5. Sinfonie Sérieuse (Symphony No.1 IN G Minor) (1842) (30:38)

6-8. Symphony No.4 In E Flat Major ("Sinfonie naïve") (1845) (27:21)

Credits :

Conductor – Roy Goodman

Cover [Illustration: "Dawn Over Riddarfjardin" (1899)] – Eugène Jansson

Leader [Swedish Radio SO] – Ulf Forsberg

Liner Notes – Roy Goodman

Orchestra – Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra

BERWALD : Symphonies Nos. 1-4 (Thomas Dausgaard) 2CD (2004) Two Version | APE (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

Tracklist 1 :

1-4. Sinfonie Sérieuse (Symphony No. 1) In G Minor

5. Erinnerung An Die Norwegischen Alpen (Memory Of The Norwegian Alps)

6-8. Sinfonie Capricieuse (Symphony No. 2) In D Major

Tracklist 2 :

1-3. Sinfonie Singulière (Symphony No. 3) In C Major

4. Elfenspiel (Play Of The Elves) Tone Painting For Large Orchestra

5-8. Sinfonie Naïve (Symphony No. 4) In E Flat Major

Credits :

Conductor – Thomas Dausgaard

Orchestra – Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra.

FRANZ BERWALD : 4 Symphonies (Gothenburg SO · Neeme Järvi) 2CD | Three Version | APE + FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

KUHLAU · BERWALD : Piano Concertos (Maurizio Paciariello · Sassari Symphony Orchestra · Roberto Diem Tigani) (2002) Two Version | APE (image+tracks+.cue), lossless

BERWALD · STENHAMMAR · AULIN : Swedish Romantic Violin Concertos (Niklas Willén · Swedish Chamber Orchestra · Tobias Ringborg) (1999) Two Version | FLAC (image+tracks+.cue), lossless

For much of the nineteenth century in Sweden, music-making was confined to small-scale chamber music at home. Ambitious composers had to move abroad to seek acceptance of their work. Berwald’s Violin Concerto was performed only once in Sweden during his lifetime, and on that occasion the audience laughed. It was not until a century later, when Tor Aulin and Wilhelm Stenhammar led a Berwald revival, that this sparkling work was performed throughout Europe. Stenhammar’s two Romances were written during one of the most creative periods of his life. Full of feeling, they are models of the genre. The two Romances were given their first performance by Tor Aulin, whose own Violin Concerto No. 3 belongs firmly to the world of Brahms and the central European romantic tradition. naxos

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

1-3. Violinkonsert I Ciss-Moll, Op 2 (21:38)

WILHELM STENHAMMAR (1871-1927)

4-5. Två Sentimentala Romanser, Op 28

TOR AULIN (1866-1914)

4-8. Violinkonsert Nr 3 I C-Moll, Op 14 (30:59)

Credits :

Conductor – Niklas Willén

Cover [Omslagsbild - "Hoga-dal På Tjörn"] – Karl Nordström

Orchestra – Svenska Kammarorkestern

Violin – Tobias Ringborg

A Bassoon in Stockholm — FRANZ BERWALD : septet & quartet • ÉDOUARD DU PUY : quintet (Donna Agrell) (2015) SACD | Two Version | FLAC (image+tracks+.cue), lossless

Chamber Works associated withthe bassoon virtuoso Frans Preumayr (1787-1853) and period instruments including a basson from c. 1820 by Grenser & Weisner

FRANZ BERWALD (1796-1868)

1-3. Septet In B Flat Major For Clarinet, Horn, Bassoon, Violin, Viola, Cello And Double Bass (23:15)

7-9. Quartet In E Flat Major For Piano, Clarinet, Horn And Bassoon (23:43)

ÉDOUARD DU PUY (1770-1822)

4-5. Två Sentimentala Romanser, Op 28

Credits :

Bassoon, Liner Notes – Donna Agrell

Cello – Albert Brüggen

Clarinet – Lorenzo Coppola

Double Bass – Robert Franenberg

Fortepiano – Ronald Brautigam

Horn – Teunis van der Zwart

Viola – Yoshiko Morita

Violin – Franc Polman

+ last month

MARTHA COPELAND — Complete Recorded Works In Chronological Order Volume 2 · 1927-1928 + IRENE SCRUGGS — The Remaining Titles 1926-1930 | DOCD-5373 (1995) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

One of many early blues and jazz women who were overshadowed and ultimately eclipsed by Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, and Bessie Smith, Martha Co...

.jpg)

.jpg)