The range of style and approach in Ives’s text-setting is startling—from simple, sentimental ballads to complex and strenuous philosophical discourses, sometimes encompassing the most dissonant and virtuosic piano parts, sometimes with the accompaniment pared down to an almost minimalist phrase-repetition. Even those composed in a superficially conventional or ‘polite’ tonal idiom usually contain harmonic, rhythmic or accentual surprises somewhere.

A particular beauty is Mists, composed in 1910. The poem is by Ives’s wife Harmony—an elegy after her mother’s sudden death that year. The manuscript, written while on vacation at Elk Lake in the Adirondacks, is dated ‘last mist at Pell’s Sep 20 1910’. This exquisite and deeply felt setting, with its brume of Impressionistic harmonies in contrary motion, is among Ives’s most atmospheric songs.

This thrilling collection also includes Ives’s War Songs and settings of Goethe. Hyperion

Gerald Finley (baritone), Julius Drake (piano)

3.3.22

CHARLES IVES : Romanzo di Central Park (Gerald Finley, Julius Drake) (2008) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

IVES : Concord Sonata • Songs (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Susan Graham) (2002) FLAC (tracks), lossless

THEO BLECKMANN & KNEEBODY - Twelve Songs By Charles Ives (2008) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

1 Songs My Mother Taught Me 7:12

Lyrics By – Adolf Heyduk

Translated By – Natalie Macfarren

2 Feldeinsamkeit / In Summer Fields 4:43

Lyrics By – Hermann Allmers

Translated By – Henry Grafton Chapman

3 At The River 6:07

Lyrics By – Robert Lowry

4 The Cage 2:44

Lyrics By – Charles Ives

5 Weil' Auf Mir / Eyes So Dark 3:45

Lyrics By – Nikolaus Lenau

Translated By – William Joseph Westbrook

6 Serenity 5:14

Lyrics By – John Greenleaf Whittier

7 In The Mornin' 4:30

Arranged By – C. Ives

Lyrics By – Trad. Spiritual

8 The Housatonic At Stockbridge 8:44

Lyrics By – Robert Underwood Johnson

9 The See'r 4:26

Lyrics By – Charles Ives

10 The New River 2:45

Lyrics By – Charles Ives

11 Like A Sick Eagle 4:42

Lyrics By – John Keats

12 Waltz 3:14

Lyrics By – Charles Ives

Credits :

Acoustic Bass, Electric Bass, Effects – Kaveh Rastegar

Arranged By – Adam Benjamin (pistas: 8), Kaveh Rastegar (pistas: 5), Nate Wood (pistas: 7), Theo Bleckmann (pistas: 6, 10 to 12)

Arranged By [Arrangements By] – Kneebody, Theo Bleckmann

Arranged By [Except Intro On 3] – Ben Wendel (pistas: 1 to 4)

Arranged By [Intro Only On 3] – Shane Endsley (pistas: 3, 9)

Band – Kneebody

Drums – Nate Wood

Piano, Electric Piano [Fender Rhodes], Electric Piano [Wurlitzer], Effects – Adam Benjamin

Tenor Saxophone, Bassoon, Melodica, Effects – Ben Wendel

Trumpet, Percussion, Effects – Shane Endsley

Voice, Electronics [Live Electronic Processing] – Theo Bleckmann

IVAN WYSCHNEGRADSKY, CHARLES IVES : Quarter Tone Pieces (Josef Christof-Steffen Schleiermacher) (2006) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

IAIN QEEN - Variations on America (American Organ Works) (2009) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Aaron Copland

Preamble (For A Solemn Occasion) (5:31)

Charles Ives

With Bold And Noble Expressivity Throughout - Allargando

Variations On 'America', S 140 (8:51)

Adeste Fidelis, S 131 (4:11)

Fugue, S 136 - 5:04

Fugue, S 135 - 3:31

Score Editor – Charles Krigbaum, John Kirkpatrick

Henry Cowell

Hymn And Fuguing Tune No. 14 - 7:16

William Grant Still

Reverie (4:38)

Samuel Barber

Slow

Prelude And Fugue (8:23)

Wondrous Love, Op. 34 (8:23)

Stephen Paulus

In Moderate Tempo - Slightly Faster - Same Tempo - With Grace - Very Much Slower

Triptych (14:40)

Organ – Iain Quinn

IVES : Concord Sonata; BARBER : Piano Sonata (Marc-André Hamelin) (2004) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

America’s two greatest twentieth-century piano sonatas are here given predictably stunning performances by Marc-André Hamelin. This is the pianist’s second recording of the Ives ‘Concord Sonata’, a piece he has played for over twenty years in performances that have often been regarded as definitive. As his thoughts on this landmark work matured, Marc became very keen to revisit the work in the studio in this 50th anniversary year of Ives’s death.

The Barber is an apt if unusual coupling. Premiered by Horowitz, with a blisteringly virtuosic final fugue written specially at his suggestion, this is one of only a few modern piano works to have become a genuine audience favourite. Hyperion

THE KNIGHTS (Eric Jacobsen, Jan Vogler) - New Worlds (2009) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The Golijov is both bristling with energy and tension and played with precision; well done, especially when one considers the rather complex rhythmic profile of the piece. Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring closes out the show, and the Knights' -- and conductor Eric Jacobsen's -- attentiveness to detail pays off in the Copland, which for some established orchestras can sound like a tired old warhorse. That said, it doesn't quite crackle with the electricity encountered in older recordings by Antal Dorati or Copland himself, but the Knights' reading is fresher than many to most interpretations of this very commonly recorded piece. Listen up, orchestras of the classical establishment: here is your competition. In order to keep pace with what the Knights can offer in lithe limberness and immediacy, the big concert orchestras might need to put in some time at the gymnasium; suffice it is to say that New Worlds is a refreshing change over usual orchestral fare. by Uncle Dave Lewis

Tracklist :

The Unanswered Question (II)

Composed By – Charles Ives

Leyendas - An Andean Walkabout

Composed By – Gabriela Lena Frank

Silent Woods (Klid)

Composed By – Antonín Dvořák

Last Round

Composed By – Osvaldo Golijov

Appalachian Spring

Composed By – Aaron Copland

Cello – Jan Vogler

Conductor – Eric Jacobsen

Orchestra – The Knights

CHARLES IVES : String Quartets (Blair String Quartet) (2006) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

Charles Ives, a New Englander by birth and character, began composing at the age of eleven, although after deciding that he would never make a living with his music he pursued a successful career in insurance. He was trained by his father George, a bandleader, who encouraged him to experiment with the unconventional techniques that were to become his signature, such as polytonality, microtones and spatial performance. Ives’s two string quartets are as unalike in origin as they are in content. The First Quartet uses his beloved revival and gospel hymns as musical sources, and its energy and originality provide an early example of Ives’s highly original creative powers. The highly complex Second String Quartet was born of a typical Ives rage against what he perceived as the effeminacy of standard string quartet performances. Ives himself summarised the work’s programme as: ‘four men – who converse, discuss, argue ... fight, shake hands, shut up – then walk up the mountainside to view the firmament’. Naxos

IVES : Piano Sonata Nr. 2 • Violin Sonata Nr. 4 (Joonas Ahonen, Pekka Kuusisto) (2017) SACD / FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

CHARLES IVES : Sonatas for Violin and Piano (Schneeberger, Cholette) (1999) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

2.3.22

CHARLES IVES : Symphonies Nº. 1 & 2 (Andrew Davis) (2015) SACD / FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Charles Ives composed his first two symphonies between 1897 and 1902, but they weren't performed until a half-century later, when Leonard Bernstein premiered the Symphony No. 2 in 1951, and Richard Bales conducted the Symphony No. 1 in 1953. The contrasts between the two symphonies are striking, since the First was a student work, composed in emulation of the European tradition, while the Second was more idiosyncratic in the use of hymn tunes, folk songs, and other Americana, all developed in a freewheeling manner that reflected Ives' eclectic musical upbringing. This 2015 hybrid SACD by Andrew Davis and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra is a straightforward presentation of both works, side-by-side, and their differences are highlighted in the styles of playing. Because the First is a late Romantic symphony, it receives a rather serious and earnest interpretation, yet this piece isn't quite convincing because it seems too much like a pastiche of Dvorák and Tchaikovsky, and Ives' personality is barely perceptible. The performance of the Second is much more in keeping with Ives' character, and the playing is as jaunty and fresh as the previous performance was brooding and sentimental. Davis and the orchestra are committed in both of these performances, though it doesn't take close listening to tell which of the two symphonies they more enjoyed playing. by Blair Sanderson

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

Symphony No. 1 (39:56)

Symphony No. 2 (37:15)

Orchestra – Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Conductor – Andrew Davis

CHARLES IVES : A Symphony "New England Holidays" • Three Places in New England • Central Park in the Dark • The Unanswered Question (Andrew Davis) (2015) SACD / FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

It used to be that the majority of good Ives recordings were American, and it was thought that you had to be American to really catch the complex web of vernacular musical references on which Ives' music rests. But it's a rare nonspecialist American listener today who will identify all the 19th century hymns and band tunes that go by, and this highly successful recording by Sir Andrew Davis and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra tackles a different difficulty with Ives: the problem of balance and clarity in his large orchestral scores. The conductor's note by Davis is worth the price of admission here, as when he points to a passage in the first movement of the Symphony: New England Holidays (sample track one) where Ives realized the difficulty of hearing a solo Jew's harp and suggested instead "half a dozen to a hundred of them." Co-starring with Davis is the Chandos engineering team, working in a couple of different Australian halls. The performances of the Holidays Symphony and the rare large version of the Orchestral Set No. 1: Three Places in New England (generally known simply by its subtitle) are rich indeed, tapestries of orchestral detail that give you the feeling this is how Ives wanted the music to be heard. And the two shorter works, presented here as Ives intended them, as entr'actes, are equally good: the final The Unanswered Question, with an impressively hushed quality throughout (putting quite the demands on the unidentified trumpeter), is a standout reading of this popular work. Strongly recommended. by James Manheim

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

A Symphony: New England Holidays (39:04)

Central Park In The Dark 8:07

Orchestral Set No. 1: Three Places In New England (19:43)

The Unanswered Question 5:02

Orchestra – Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Conductor – Andrew Davis

CHARLES IVES : Symphony No. 3 "The Camp Meeting" • Symphony No. 4 • Orchestral Set No. 2 (Sir Andrew Davis) (2017) SACD | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

With this release, Sir Andrew Davis and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra round out their Ives cycle in superb form. Recordings of Ives, unlike Gershwin, by groups outside of the U.S. may still be comparatively rare, but Davis has nailed the essential diverse, dense networks of Ives' language, assisted by new performing editions and by excellent Chandos engineering in two different Melbourne venues, thereby keeping the multiple strands of the music clear. Sample the first movement of the Symphony No. 3 ("The Camp Meeting"), where Davis gives some lyricism to the chains of thirds that make up much of the material, and correctly sees them as a quiet pastoral foil to the more public marches and hymn tunes that come later. The Symphony No. 4 has a visionary sweep here that it attains in few other recordings, and part of the reason is the dreamy tones coaxed from the Melbourne Symphony Chorus by chorus master Anthony Pasquill. You get a star (or near-star) pianist in the Fourth Symphony here, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, which is unusual. But Davis has the music under enough control to bring the piano unusually far forward in the music, and to open up a whole new set of internal relationships in the work. The Orchestral Set No. 2, with its depiction of a crowd in New York hearing the news of the sinking of the Lusitania, is also haunting and seems to acquire new relevance. This is an absolutely top-notch Ives recording. James Manheim

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

1-3 Orchestral Set No.2 (17:39)

4-6 Symphony No.3 'The Camp Meeting' (21:09)

7-10 Symphony No.4 (31:51)

Orchestra – Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Chorus Master – Jonathan Grieves-Smith (1-3)

Conductor [Assistant] – Brett Kelly (1-3)

Piano – Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (7-10)

Conductor – Andrew Davis

CHARLES IVES : Symphony Nr. 2 • Central Park In The Dark • The Unanswered Question • Tone Roads No. 1 • Hymn For Strings • Hallowe'en • The Gong On The Hook And Ladder (Leonard Bernstein) (2001) APE (image+.cue), lossless

1-5 Symphony No. 2

6 The Gong On The Hook And Ladder Or Firemen's Parade On Main Street 2:13

7 Tone Roads No. 1 3:16

8 Hymn: Largo Cantabile (For String Orchestra) 3:43

9 Hallowe'en 1:56

10 Central Park In The Dark 7:11

11 The Unanswered Question 6:07

Conductor – Leonard Bernstein

Orchestra – New York Philharmonic

IVES : Symphonies Nº 1 & 4 • Central Park in the Dark (Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Litton) (2006) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

For the Charles Ives enthusiast on the left side of the Atlantic "pond," this Hyperion release, Ives: Symphonies 1 & 4, brings up some red flags upon first appearance. While the movers and shakers in English classical music circles are famously xenophobic, they tend to fault Americans for being equally so, and when an American sees the music of Charles Ives on an English label, that instinctively comes to mind. These are not English performances, though; they were made at McDermott Concert Hall in Dallas and feature the Dallas Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Andrew Litton. That brings up another red flag: Litton has already recorded Ives' Orchestral Set No. 1: Three Places in New England with Dallas for the late Dorian label, and that hardly set the world on fire at the time of release (in 1996). On the other hand, it is not as though record companies are trying to outdo one another recording Ives' symphonies at present, so it might not be a bad idea to give Litton's Ives: Symphonies 1 & 4 a chance. The Dallas Symphony and the music of Ives already have an established history which goes back to at least the 1960s, when conductor Donald Johanos led the DSO in a widely circulated performance of Ives' Holidays Symphony for Vox Turnabout.

The performance of Ives' Symphony No. 1 here is of the highest caliber. Ives regarded it as one of his "weak sisters," a school assignment barely worth discussing, and annotator Jan Swafford, who should know better, sides with the composer in this instance. Nevertheless, Ives' First has a gentle, persuasive power uniquely its own that has hooked some listeners who could care less about Ives' noisy orchestral sets and the Symphony No. 4; Litton manages to tease this persuasiveness carefully out of the Dallas Symphony. Additionally, the score utilized here seems to make little to no use of any of Ives' variant concepts for this work -- not a desirable state of affairs for all of Ives' symphonies, but not a bad idea for this one. Ives: Symphonies 1 & 4 might contain the finest Ives First to appear on record since André Previn's with the London Symphony Orchestra back in 1971. Ironically, Litton's ability to make the Dallas Symphony sound like an English, or at least European, orchestra is one of the things that makes this recording so good; notwithstanding the flag-waving xenophobes out there.

The Symphony No. 4 and Central Park in the Dark, however, are another matter. Litton does make use of the optional chorus in the first movement of the Fourth, and it is nicely done. However, Hyperion's recording is none too friendly to the extremes of volume in this symphony. Litton manages to get very good results out of the quartertone section in the strings that open the second movement "comedy," but it is hard to hear, even when played back at top volume. The same goes for Central Park in the Dark, marked to be played very quietly in the score, but just because you can get that quiet doesn't mean that you should do so on a recording, as loud sections might terminate one's speakers with prejudice. Nonetheless, another aspect of this particular Fourth that may or may not be so desirable is that Litton has shaped it so carefully. The whole work has been marked out to separate foreground elements from the rest, tempering Ives' divine approach to chaos. This may prove a boon to those who can generally make no sense of the Fourth, but for experienced Ivesians, part of the appeal of the Fourth is its wacky and transcendental messiness. Of course, such does not apply to the Fourth's traditional third movement, which comes off quite well here. In general, the rule with Litton's Hyperion traversal through Ives' symphonies seems to be the more stylistically conservative a given Ives symphony is, the better the results. If so, then if you could own only one of the two volumes, this one would not be the more desirable choice. by Uncle Dave Lewis

CHARLES IVES (1874-1954)

Symphony No 1 [37'10]

Symphony No 4 [30'52]

Central Park in the Dark [9'46]

Orchestra – Dallas Symphony Orchestra

Conductor – Andrew Litton

IVES : Symphonies Nº 2 & 3 • General William Booth enters into Heaven (Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Litton) (2008) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Ives: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 3 is the second disc in Andrew Litton's cycle of Charles Ives' symphonies for the Hyperion label with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. Of the two discs devoted to this series, this is better from a performance standpoint, as the first disc suffers from a so-so Symphony No. 4 even as it sports a terrific Symphony No. 1. The recorded sound here is something of a mixed bag as it is dark and fuzzy at the edges, although in terms of distance relative to volume it is very, very well made. In the Symphony No. 2, later movements are better than the earlier ones, with a stronger sense of pickup and forward momentum. The opening Andante moderato lacks focus and the strings are rather sludgy in the first two movements, but the brass section sounds very good in the Allegro molto vivace. The famous final discord, though, lacks punch. Hyperion's recording of the percussion parts in this Symphony No. 2 come through with more clarity than on any other recording.

Symphony No. 3 is probably the greatest of Ives' symphonies, so the bar for any recorded version is set very high indeed, particularly as there is a splendid, thoroughly transparent version made for Mercury Living Presence by conductor Howard Hanson that's hard to beat. Here Litton attempts to put some distance between himself from other recordings by observing strict adherence to the pacing of the symphony and utilizing many of Ives' suggested "shadow parts" -- discordant patches of music that are heard as if in a distance. In this instance, the recording's great sense of interior depth does work well, as these parts do not intrude on the main texture and are heard as "shadows," as Ives intended. It's a little harder to get used to the strict observance of tempo; most recorded versions don't make much of a distinction between the tempi of the three movements except that the second movement is a tad faster than the first. Here Litton spells it out and makes each movement roll at a distinct speed. It leaves one with a mixed impression, but overall it is a very good realization of the Symphony No. 3 and it demonstrates that this symphony, despite its grounding in a traditional style, is as open to nearly the same variety of interpretations as the ones that follow -- the Symphony No. 4 and the Universe Symphony.

John J. Becker's mini-oratorio-like arrangement of Ives' General William Booth Enters into Heaven was made at Ives' instigation in the mid-'30s as the composer by then did not have the stamina, or the eyesight, to see through to full fruition nine pages of sketches already at hand. It hasn't been recorded very often, although a very fine version was made for Columbia Masterworks in 1966 with Archie Drake singing the solo bass part with chorus and orchestra under the leadership of Gregg Smith, and this has never appeared on CD. With that recording, the solo singing was fabulous, but the orchestra and chorus were muddy and indistinct; here, the chorus and orchestra are just right -- especially the chorus -- but Donnie Ray Albert's bass is semi-buried and sounds "squashed." Despite such middling complaints, one must give credit where it is due and admit the choice of this work was a nice and imaginative touch as filler to these two symphonies. Litton's Hyperion set of Ives' symphonies, in sum, does put some pressure on Michael Tilson Thomas' set for CBS, even if it doesn't have the edge. by Uncle Dave Lewis

CHARLES IVES (1874-1954)

Symphony No 1 [37'10]

Symphony No 3 'The Camp Meeting' [23'48]

General William Booth Enters Into Heaven [5:13]

Arranged By – John J. Becker

Baritone Vocals [Baritone] – Donnie Ray Albert

Choir – Dallas Symphony Chorus

Chorus Master [Chorus Directed By] – David R. Davidson

Words By – Vachel Lindsay

Orchestra – Dallas Symphony Orchestra

Conductor – Andrew Litton

Leader – Emanuel Borok

CHARLES IVES : Symphony No.3 • Ragtime Dances • Robert Browning Overture (Michael Stern) (2006) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

CHARLES IVES : Robert Browning Overture • Symphony No. 2 (Kenneth Schermerhorn) (2000) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Hamburg - brings the movement to its breathless conclusion. The third movement, Adagio cantabile, first saw light of day as the slow movement to Ives's First

Symphony but was withdrawn at Parker's request. Beginning solemnly, quotes from Beulah Land and Materna (now known as ‘America the Beautiful’) are joined to extend the theme. This is followed by an Andante episode based on the hymns Missionary Chant and Nettleton. A final statement of the Beulah/Materna group and a quiet horn call bring the movement to a close. Following the model of Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony, Ives introduces a cyclic return of his first movement to serve as his fourth movement - really an extended introduction to the finale. Beginning this with a lively passage reminiscent of folk fiddling, the Stephen Foster song Camptown Races is introduced in the horns, becoming the main theme of the movement. A trumpet blast of Reveille announces the coda, where Wake Nicodemus, Pig Town Fling, and Columbia are sounded simultaneously, climaxing in one of the greatest symphonic pies-in-the-face ever hurled by a composer at his audience.

Ives had originally planned a cycle of overtures called Men of Literature. Only the Robert Browning Overture was completed, sketches for others finding their way into the Concord Sonata and much else. If the Second Symphony is one of Ives's most accessible works, the Robert Browning Overture is one of his most challenging. Ives was never satisfied with his attempt to evoke what he described as Browning's 'surge into the baffling unknown' and later repudiated the work. Its mysterious introduction is interrupted by a seething passage in the strings and an angular, atonal march whose theme is played in a series of canons between brass, woodwinds, and strings. Following a highly dissonant climax, an Adagio provides some repose. The return to the opening material and an extended recapitulation of the densely scored, canonic march, climaxes with a long-held pedal G-sharp and a ferociously dissonant chord, resolving into one of Ives's 'shadow chords.' Brief overlapping solos for the brass take us into the densely polyrhythmic coda. The work shrieks to a stop, revealing the opening chords of the Adagio, played almost imperceptibly in the strings. Joshua Cheek

CHARLES IVES (1874-1954)

Robert Browning Overture 00:24:48

Symphony No. 2

Orchestra – Nashville Symphony Orchestra

Conductor – Kenneth Schermerhorn

IVES/BRANT : A Concord Symphony; COPLAND : Organ Symphony (San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson Thomas) (2011) FLAC (tracks), lossless

The first item on the program here is, as the potential buyer may have guessed, an orchestral transcrption of Charles Ives' Piano Sonata No. 2, known as the Concord Sonata. But it requires a little more explanation. Orchestrator Henry Brant was a Canadian-American composer of an experimental bent who became, one learns from the booklet, "obsesssed" with the Concord Sonata and worked on an orchestral version in his spare time for the startlingly long period of 36 years, from 1958 to 1994. Further, he did not try to turn it into another Ives symphony, as the title might imply, "but rather to create a symphonic idiom which would ride in the orchestra with athletic surefootedness and present Ives' astounding music in clear, vivid, and intense sonorities." The result is quite unusual: not exactly Ivesian, but wholly absorbing in this reading by the eternally fresh Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony. Brant's version is something like a guided tour through the work, with the swirling flow of musical existence pared away from the sonata's special features. The recurring references to Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67, are pointed up in this version, and the evocations of vernacular American music (hear the brass band passages) that are part of the torrent in the piano version are here restored to something like their original sounds. Again, it's not exactly Ives, but the Concord Sonata has a way of bursting over its pianistic confines anyhow; there is an optional flute part for the finale that is too rarely performed. The second piece on the program is likewise underperformed, Copland's short three-movement Organ Symphony of 1925 is perhaps the one that most clearly reflects his own personality among his early works. Written in an idiom that clearly owes much to Copland's recent studies in Paris, it nevertheless works in big lyrical tunes and rollicking fun. Tilson Thomas and organist Paul Jacobs give the work its due and are sensitive to the clever ways of balancing the organ with orchestral textures. A highly enjoyable album of unusual Americana. by James Manheim

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

A Concord Symphony (50:05)

Orchestrated By – Henry Brant

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

Organ Symphony (27:02)

Organ – Paul Jacobs

Orchestra – San Francisco Symphony

Conductor – Michael Tilson Thomas

1.3.22

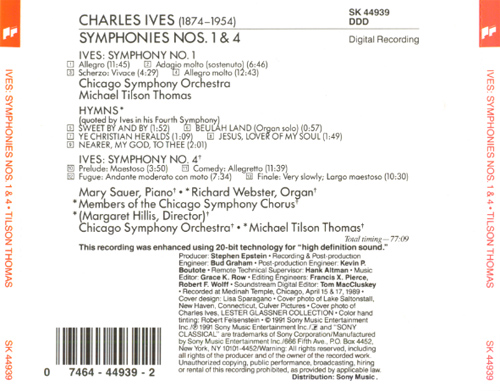

IVES : Symphonies Nos. 1 & 4 · Hymns (Chicago Symphony Orchestra & Chorus · Michael Tilson Thomas) (1991) APE (image+.cue), lossless

+ last month

FRANKIE "Half-Pint" JAXON — Complete Recorded Works In Chronological Order Volume 3 · 1937-1940 (1994) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

After cutting records with the Harlem Hamfats in Chicago during the years 1937 and 1938, Frankie "Half Pint" Jaxon made his final ...

.jpg)

.jpg)