After listening to Revenant's massive Albert Ayler box set, Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962-70), a pair of questions assert themselves in the uneasily settling silence that follows: who was Albert Ayler, and how did he come to be? At the time of this box set's release 26 years after the Cleveland native's mysterious death -- his lifeless body was found floating in New York's East River, without a suicide note -- those questions loom larger than ever. Revenant's amazing package certainly adds weight and heft to the argument for Ayler's true place in the jazz pantheon, not only as a practitioner of free jazz but as one of the music's true innovators. Ayler may have been deeply affected by the music of Ornette Coleman, but in turn he also profoundly influenced John Coltrane's late period.

After listening to Revenant's massive Albert Ayler box set, Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962-70), a pair of questions assert themselves in the uneasily settling silence that follows: who was Albert Ayler, and how did he come to be? At the time of this box set's release 26 years after the Cleveland native's mysterious death -- his lifeless body was found floating in New York's East River, without a suicide note -- those questions loom larger than ever. Revenant's amazing package certainly adds weight and heft to the argument for Ayler's true place in the jazz pantheon, not only as a practitioner of free jazz but as one of the music's true innovators. Ayler may have been deeply affected by the music of Ornette Coleman, but in turn he also profoundly influenced John Coltrane's late period.

The item itself is a deeply detailed 10" by 10" black faux-onyx "spirit box," cast from a hand-carved original. Inside are ten CDs in beautifully designed, individually colored rice paper sleeves. Seven are full-length music CDs, two contain interviews, and one is packaged as a replica of a recording tape box, containing two tracks from an Army band session Ayler participated in. Loose items include a Slug's Saloon handbill, an abridged facsimile of Amiri Baraka's journal Cricket from the mid-'60s containing a piece by Ayler, a replica of the booklet Paul Haines wrote for Ayler's Spiritual Unity album, a note Ayler scrawled on hotel stationery in Europe, a rumpled photograph of the saxophonist as a boy, and a dogwood flower. Finally, there is a hardbound 209-page book. It contains a truncated version of Val Wilmer's historic chapter on Ayler from As Serious As Your Life, a new essay by Baraka, and biographical and musicological essays by Ben Young, Marc Chaloin, and Daniel Caux. In addition, there are testimonies by many collaborators, full biographical essays of all sidemen, detailed track information on the contents, and dozens of photographs.

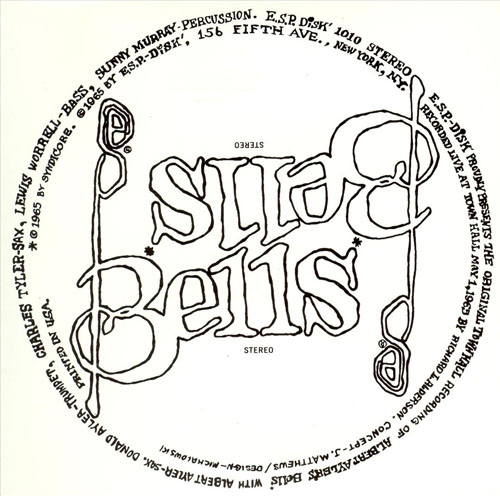

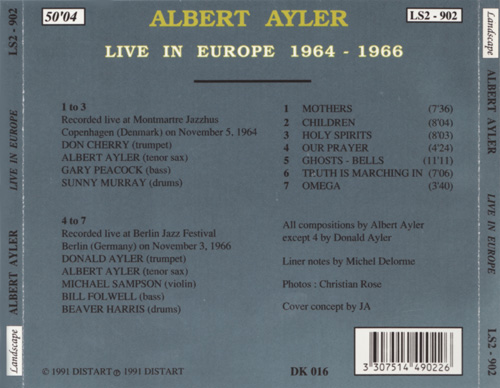

Almost all this material has been, until now, commercially unavailable. Qualitatively, the music here varies, both artistically and mechanically. Some was taken from broadcast and tape sources that have deteriorated or were dubious to begin with, but their massive historical significance far outweighs minor fidelity problems. Chronologically organized, the adventure begins with Ayler's earliest performances in Europe fronting a thoroughly confounded rhythm section that was tied to conventional time signatures and chord changes. Ayler, seemingly oblivious, was trying out his new thing in earnest -- to the consternation of audiences and bandmates alike. How did a guy who played like this even get a gig in such a conservative jazz environment? Fumbling as this music is, it proves beyond any doubt Ayler's knowledge and mastery of the saxophone tradition from Lester Young to Sonny Rollins. Ayler's huge tone and his amazing, masterfully controlled use of both vibrato and the tenor's high register are already in evidence here. Following these, there is finally recorded evidence to support Ayler playing with Cecil Taylor in Copenhagen in 1962. This is where he met drummer Sunny Murray who, along with bassist Gary Peacock, formed the original Ayler trio. Their 1964 performances at New York's Cellar Café are documented here to stunning effect. Following these are phenomenal broadcast performances from later that year that include Don Cherry on trumpet in France.

Other discs here document Ayler's sideman duties: with pianist Burton Greene's quintet in 1966 (with Rashied Ali), a Pharoah Sanders band with Sirone and Dave Burrell, a Town Hall concert with his brother Donald's sextet that also included Sam Rivers, and a quartet with Donald, drummer Milford Graves, and bassist Richard Davis playing at John Coltrane's funeral. These live sessions have much value historically as well as musically, but are, after all, blowing sessions -- though they still display Ayler as a willing and fiery collaborator who upped the ante with his presence. Though he arrived fully formed as a soloist, his manner of trying to adapt to other players and bring them into his sphere is fascinating, frustrating, and revealing.

Ayler's own music is showcased best when leading his own quartets and quintets, and there are almost four discs' worth of performances here. Much of this music is with the classical violinist Michel Sampson and trumpeter Donald Ayler with alternating rhythm sections. Indeed, the quintet gigs here with Sampson and Donald in the front line that used marching rhythms and traditional hymns as their root may not be as compelling sonically as the Village Vanguard stuff issued by Impulse!, but they are as satisfying musically. The various rhythm sections included drummers Ronald Shannon Jackson, Allen Blairman, Muhammad Ali, Beaver Harris, and Bernard Purdie, and bassists Bill Folwell, Steve Tintweiss, Clyde Shy (Mutawef Shaheed), pianist Call Cobbs, and tenor saxophonist Frank Wright. What is clearly evident is that the only drummer with whom Ayler truly connected with, the only one who could match his manner of playing out of time and stretching it immeasurably, was Murray, who literally played around the beat while moving the music through its dislocated center.

The late music remains controversial. Recorded live in 1968 and 1970 in New York and France, it illuminates the troublesome period on Ayler's Impulse! recordings, New Grass and Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe. In performance, struggling and ill-conceived rhythm sections try to comprehend and articulate the complex patchwork of colors, motivations, and adventurous attempts at musical integration with the blues, rock, poetry, and soul Ayler was engaging instrumentally and -- with companion Mary Parks -- vocally. Ayler's own playing remains unshakable and revelatory, stunning for its ability to bring to the surface hidden melodies, timbres, and overtones and, to a degree, make them accessible. His solos, full of passion, pathos, and the otherworldly, pull everything from his musical sound world into his being and send it out again, transformed, through the horn.

Ayler is credited with the set's title, in that he once said in an interview: "Trane was the father. Pharoah was the son. I was the Holy Ghost." While it can be dismissed as hyperbole, it should also be evaluated to underscore the aforementioned questions. Unlike Coltrane and Sanders whose musical developments followed a recorded trajectory, Ayler, who apparently had very conventional beginnings as a musician, somehow arrived on the New York and European scenes already on the outside, pushing ever harder at boundaries that other people hadn't yet even perceived let alone transgressed. Who he was in relation to all those who came after him is only answered partially, and how he came to find his margin and live there remains a complete cipher. What Revenant has accomplished is to shine light into the darkened corners of myth and apocrypha; the label has added flesh-and-bone documented history to the ghost of a giant. Ayler struggled musically and personally to find and hold onto the elusive musical/spiritual balance that grace kissed him with only a few times during his lifetime -- on tape anyway. But the quest for that prize, presented here, adds immeasurably to both the legend and the achievement.

-> This comment is posted on Allmusic by Thom Jurek, follower of our blog 'O Púbis da Rosa' <-

All Tracks & Credits