'I repeat what I said to you back in Russia: you are, in my opinion, the greatest composer of our time.' – Sergei Rachmaninov (1921)

'I repeat what I said to you back in Russia: you are, in my opinion, the greatest composer of our time.' – Sergei Rachmaninov (1921)

It would be hard to overestimate the importance of this set.

Medtner's piano compositions are arguably the last area of great Romantic piano repertoire to be discovered. His music is difficult, both technically and intellectually, and does not 'play to the gallery', which may explain its neglect. But once his world has been entered it proves endlessly fascinating and compelling, his work growing in stature with every hearing until one is left in no doubt as to its overwhelming effect.

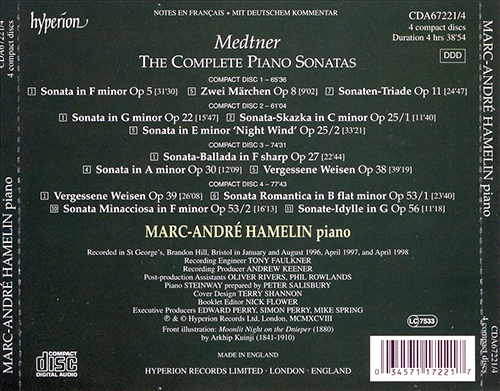

Central to his output are the 14 Piano Sonatas (though the title covers a multitude of structures and sizes) and here for the first time we have the complete cycle recorded by one artist. Hyperion Tracklist & Credits :

4.9.24

MEDTNER : The Complete Piano Sonatas · Forgotten Melodies I - II (Marc-André Hamelin) 4xCD (1998) APE (tracks), lossless

6.4.22

LIADOV • MEDTNER • SCRIABIN • PROKOFIEV • BORODIN • DEBUSSY • GOLTZ • GLAZUNOV • LISZT • CHOPIN - Recordings : 1937-1953 (Vladimir Sofronitsky) (2007) 2CD / APE (image+.cue), lossless

CD1

CD1

Anatoly Liadov

1 Prélude in B Minor Op. 11 No. 1 (14. 6.1949)

2 Music Box Op. 32 (14.6.1949)

3 Waltz in E Major Op. 57 No. 3 (15.7.1949)

Nikolai Medtner

4 Fairy Tale Op. 20 No. 2 (2.7.1947)

Alexander Scriabin

5-6 2 Préludes Op. 27 (28.3.1938)

Fryderyk Chopin

7 Mazurka Op. 41 No. 2 (1937-1941)

8 Waltz Op. 70 No. 1 (5.1941)

9 Etude Op. 10 No. 4 (16.6.1937)

Franz Liszt

10 Concert Etude S145 "Gnomenreigen" (25.6.1937)

Boris Goltz

11 Prélude in E Minor (17.11.1938)

12 Scherzo in E Minor (17.11.1938)

Alexander Borodin

13 Petite Suite (Au couvent, Intermezzo, Mazurka I, Mazurka II Rêverie, Sérénade, Nocturne (12.7.1950)

Dmitri Kabalevsky

14-16 Sonatina in C Major Op. 13 No. 1 (1953)

Sergei Prokofiev

17-20 Four Taies of a Grandmother Op. 31 (2.12.1946)

21 Vision fugitive Op. 22 No. 7 (1953)

22 Sarcasm Op. 22 No. 7 (1953)

CD2

Prokofiev

1-6 6 Pièces for Piano from Op. 12 (1953)

Anatoly Liadov

7-11 Six Preludes

Alexander Glazunov

12 Prelude In D Flat Major Op 49 No 1

13 Prelude & Fugue In A Minor Op 101 No 1

Claude Debussy

14 Prélude: Livre II "Feuilles Mortes"

15 Prélude: Livre II "Canope"

16 Children's Corner: "Serenade Of The Doll"

Alexander Scriabin

17 Piano Sonata No 3 Op 23

Piano – Vladimir Sofronitsky

16.1.22

MEDTNER : Piano Concerto No 2 In C Minor • Piano Concerto No 3 In E Minor (Nikolai Demidenko · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Jerzy Maksymiuk) (1992) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 2 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

As a composer, a recluse who shunned publicity and self-promotion, Medtner, a noted Beethovenian no less than an ardent post-Schumannite, in Glazunov’s opinion (Paris, 1934), ‘firm defender of the sacred laws of eternal art’, was a musician steeped in Teutonic Tradition: the critic Sabaneiev estimated him to be ‘the first real, actual Beethoven in Russia—one who did not imitate but continued the master’s work’. Among his own compatriots he was drawn to early Scriabin, but had a higher regard for Tchaikovsky and Borodin. Chopin and Liszt, too, were happy hunting grounds. Like Chopin, Medtner expressed himself almost exclusively through the medium of the piano. Like Chopin, he knew how to invest a miniature with large-scale tension, how to generate a grand design. No salon soufflé journalist, his concern always was with the massive—as three piano concertos, a piano quintet, three sonatas with violin and over a dozen of imposing dimension for piano, plus a fine heritage of songs (recorded in their time by both Slobodskaya and Schwarzkopf) impressively testify. For sheer originality, his famous Skazki or ‘Legends’ (‘Fairy Tales’)—mercurial, fantastical, Russianized narratives of the soul, suggestive yet curiously private—are unlike anything else in the repertoire.

‘By far the most interesting and striking personality in modern Russian music is that of Nicolas Medtner’, avowed Sorabji in Around Music (1932). ‘If only for his absolute independence and aloofness from the Stravinsky group and its satellites on the one hand, and his equally marked detachment from the orthodox academics grouped around Glazunov and the inheritors of the Tchaikovsky tradition on the other … like Sibelius, Medtner does not flout current fashions, he does not even deliberately ignore them, but so intent on going his own individual way is he that he is simply unconscious of their very existence. In a word, he has made for himself, by the sheer strength of his own personality, that impregnable inner shrine and retreat that only the finest spirits either dare or can inhabit.’ Among the most enigmatic figures of our century, Medtner was an apostle of conscience. He placed a premium on baroque polyphony, on classical structure, on a manner of thematic integration and cyclic metamorphosis romantic in legacy. He celebrated, he developed, he concentrated the sonata ideal. He was a resolute tonalist, a poetic melodist of the old guard.

‘Everything [Medtner] wrote’, Gerald Abraham remarks, ‘is perfectly fashioned, complete in every sense of the word … his music ‘wears’ extremely well … subjective lyrical emotion: that is the essence of Medtner’s art. He sometimes gives his pieces suggestive titles, but they are never programmatic in the usual sense of the word … titles are the merest hints to guide the listener’s fantasy.’ Ernest Newman believed that Medtner was ‘one of those composers who are classics in their lifetime. He does what every notable composer has done—takes the current language of music, impresses his own personality on it, extends its vocabulary, and modifies its grammar to suit his own ends, and then gets on with the simple business of saying what he thinks in the clearest terms possible … his music is not always easy to follow at a first hearing, but not because of any extravagance of thought or confusion of technique, it is simply because this music really does go on thinking from bar to bar, evolving logically from its premises. Perhaps the technical secret of its vitality is its rhythm … each work is an individual self-evolving organic unity.’ Another contemporary, the philosopher Ivan Ilyin, perceived that in Medtner we have an example of a musician attuned to the primordial. ‘Medtner’s music astonishes and delights’, he says, ‘not only by the wealth and breadth of its melodies that seem to be living and breathing, but also by their inexpressible primariness. This may lead to actual mistakes and illusions: you may fancy that you have heard this melody before … but where, when, from whom, in childhood, in a dream, in delirium? You will puzzle your head and strain your memory in vain: you have not heard it anywhere: in human ears it sounds for the first time … and yet it is as though you had long been waiting for it—waiting because you ‘knew’ it, not in sound, but in spirit. For the spiritual content of the melody is universal and primordial … it is as though age-long desires and strivings of our forebears were singing in us; or, as though the eternal melodies we had heard in heaven and preserved in this life as ‘strange and lovely yearnings’, were remembered at last and sung again—chaste and simple.’

At once Germanic, Frankish, Russian, a man defiantly resistant of labelling or bracketing, Medtner’s credo is expressed in unequivocal terms in his book The Muse and the Fashion (published in Paris in 1935, with the help of his friend Rachmaninov): ‘I do not believe in my dicta on music, but in music itself. I do not wish to communicate my thoughts on music, but my faith in music … the Theme is above all in intuition (in German ‘einfall’). It is acquired, not invented. The intuition of a theme constitutes a command. The fulfilment of this command is the principal task of the artist, and in the fulfilment of this task all the powers of the artist himself take part. The more faithful the artist has remained to the theme that appeared to him by intuition, the more artistic is this fulfilment and the more inspired his work … the theme is the most simple and accesible part of the work, it unifies it, and holds within itself the clue to all the subsequent complexity and variety of the work … the theme is not always, and not only, a melody … it is capable of turning into a continuous melody the most complex construction of form … melody, as our favourite and most beautiful form of the ‘theme’, should actually be viewed only as a form of the theme … form (the construction of a musical work) is harmony … form without contents is nothing but a dead scheme. Contents without form, raw material. Only contents plus form is equal to a work of art … time (tempo) is the plane of music, but this plane, in itself, is not rhythm … a neglect of rhythm makes musical form the prose, and not the poetry, of sound … song, poetry and dance are unthinkable without rhythm, which not only bring them into close relation, but often unites music, poetry and dance into one art, as it were … sonority (dynamics, colour, the quality of sounds) can never become a theme. While the other elements appeal to our spirit, soul, feeling, and thought, sonority in itself, being a duality of sound, appeals to our auditory sensation, to the taste of our ear, which in itself is capable merely of increasing, or weakening, our pleasure in the qualities of the object, but can in no way determine its substance or value … where thought and feeling confer with each other, you will find the artistic conscience. Inspiration comes, where thought is saturated in emotion, and emotion is imbued with sense …’

In Moscow Medtner studied piano at the Conservatoire. As a composer, though he had some lessons from Arensky and Taneyev, he was essentially self-taught: Taneyev used to like to say he was born with the knowledge of sonata-form within him—that was enough. In Richard Holt’s Medtner memorial symposium (1955), a book well-known in Russia, Ilyin (echoing the composer himself) suggests that he was in fact one who never actually invented anything: rather, he listened, he was the vessel through which music passed. His protagonist sonata themes, he argues, ‘stand in need of each other … they may intersect or destroy each other … they may comfort, purify, enlighten each other, and work together for common victory and reconciliation. They live in creative intercommunion …’ Discussing the elements of Medtner’s music, ‘all his modulations’, he says, ‘have the spiritual meaning of emotional ‘concession’, or of ‘stepping back in a dance’, or of comfort in sorrow, or of retreat into the shadow and darkness, into the world beyond; not one of his tonalities is accidental; his counterpoint expresses the spiritual consonance, dissonance and assimilation of themes … fugue is used by him to indicate that a given theme has been accepted on every plane of musical reality; all his ritardandos and syncopations … all his demands for legato or staccato, all his naturals are full of spiritual significance …’ Medtner’s own definition of the sonata principle was as a complex phenomenon ‘genetically tied to the simplicity of the song-form; the song-form is tied to the construction of a period; the period to a phrase; the phrase to the cadence; the cadence to the construction of the mode; the mode to the tonic.’

The Second Piano Concerto (1920/27) was first performed in Moscow, conducted by the composer’s brother. Medtner inscribed it to Rachmaninov—who returned the compliment by dedicating to him his own contemporaneous Fourth. Intriguingly, the two works are like an exchange of ‘musical letters’. Opening with a brilliant sonata-form Toccata (unusual for the substance of its reprise taking the guise of an ambitiously scaled solo cadenza), Medtner’s is overtly organized in the Rachmaninov manner: with similarly breathed and elaborated melodies; an A flat tripartite slow movement (Romance) enclosing a central agitato (à la the Rachmaninov C minor); and a final Divertimento-Rondo in the major that indulges, on the one hand, in the kind of architectural excesses found in Rachmaninov Three, and, on the other, in references to one of Rachmaninov’s songs. In his concerto (notably the finale), Rachmaninov pays homage specifically to Medtner’s peculiarly individual rhythmic style. Essentially, it must be stressed, however, that what these exchanges are about is tribute, not pastiche. Medtner is no more poor man’s Rachmaninov than Rachmaninov is rich man’s Medtner: each was possessed of a voice distinctively his own (in Medtner’s case especially so in the developmenal aspects of his Romance). During the thirties, following its first English performance (under Landon Ronald at a Queen’s Hall Philharmonic Society concert, All Saints Day, 1928), Sorabji placed a high value on the Second Concerto. Offering ‘splendid opportunities to first class pianists, musically and technically’, he thought its neglect ‘a scandal’. In 1948 Medtner recorded it with the Philharmonia under Dobroven.

Premiered by the composer and Sir Adrian Boult at the Royal Albert Hall, 19 February 1944, promoted by the PRS, the wartime Third Concerto, or ‘Concerto-Ballade’, is dedicated to the Maharajah of Mysore, ‘with deep gratitude for the appreciation and furtherance of my work’. Begun in London and completed in Warwickshire between circa 1940 and 1943, it is in three movements played without a break—the first flexible in tempo, the second an Interludium, ‘Allegro’ yet at the same time ‘molto sostenuto e misterioso’, the third an ‘Allegro molto’ climaxing in a coda more temporally fluid. Ending in E major but for much of the time oscillating unpredictably between E minor and G major, the Third is like a wonderfully free fantasia, a written-out improvisation with orchestra. Manifestly, the first movement, in its surges of imagination and turbulence is a person talking—at once considered yet free, determined yet yielding, long in sentence, short in sentence, elastic in phrasing and cadence. Calling it enchanted, it ‘moves in a kind of dream world’, Holt says, ‘with occasional intrusions of human passion and conflict’. Its structure defies ready explanation: concerned with sensations of ebb and flow, it is so remarkably veiled and aurally unapparent that to reveal it at all might only destroy it. Externally, its most obvious feature is the presence of a resolute motto theme, an idée fixe which, in best Berlioz-Tchaikovsky tradition, Medtner brings back in the Interludium and finale to impart to the whole a unity musically and psycho-dramatically important.

That Medtner’s music is unknown is unjustifiable. An alloy of the intensest of emotions and sounds, of the most subtly variegated rythmic life, it can, it’s true, often overcome one’s ability to perceive at first hearing, it can overload the circuitry of our mind. Medtner’s most complex work does not clarify easily. But this should not deter us. Creatively the equal of his two most famous emigré compatriots, Rachmaninov and Stravinsky, metaphorically like an Arthurian knight of old impassioned by his lady, Medtner was a man of righteous principle who lived for music: a quiet man, ‘a gentle lion’ large of head and blue of eye, a private man whose family was the hub of his existence. As a pianist, if asked, he would play in concert (to be adored by the cognoscenti), he would broadcast for the BBC; if he wasn’t, he wouldn’t (the competitive streak was foreign to his temperament). His ‘Appassionata’ was famous. His Beethoven Four, too, and his Rachmaninov and Schubert and Bach—paradoxically, music often directly in conflict with the quintessentially high Romantic melos of his own. At the piano, offering in his performances an overview crystallized out of the wisdom of age and the excitement of youth, his posture (very still, eyes shut) was Michelangeli-like. Reminiscing forty years ago, Arthur Alexander remembered how ‘… he possessed to an acute degree the rare power of colouring melodically passages that in the hands of others remained mere notes, and his subtleties of nuance and pedal were unforgettable. No one (except perhaps Josef Hofmann) produced so much effect with so little visible means …’ Medtner was an artist in love with the beauty of his muse. He played for beauty’s sake—and he composed for beauty’s sake.

Being a Russian is a duty. For Medtner, coming to England did nothing to change that. The Moscow nights, the Russian springs, the basilicas and bards of his young manhood: such was his heritage, a chalice of dreams and memories to hold for always. Prince of truth, he was one of Russia’s great sons. Hyperion

Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951)

Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 50 [38'20]

Piano Concerto No 3 in E minor Op 60 [35'27]

Credits :

Conductor – Jerzy Maksymiuk

Leader – Geoffrey Trabichoff

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Nikolai Demidenko

MEDTNER : Piano Concerto No 1 In C Minor • Piano Quintet In C Major (Dmitri Alexeev · BBC Symphony Orchestra · Alexander Lazarev) (1994) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 8 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

When one considers the life of Nikolai Karlovich Medtner it is impossible not to be amazed by his strange, tragic and yet marvellous destiny. He was recognized in Russia at the beginning of the twentieth century as one of the most important composers and was, with Scriabin and Rachmaninov, an extremely influential, almost ‘cult’ figure for a whole generation of the Russian intellectual élite. He was also a great pianist and an outstanding musical thinker. His personality was completely divorced from everyday life, but the depth and power of his intellect, entirely absorbed in music, philosophy and the history of culture, were deeply respected by such contemporaries as Nikisch, Rachmaninov, Furtwängler, Koussevitsky, Glazunov and Prokofiev. There is thus something of a paradox in the fact that for the last thirty years of his life, when he lived in the West, he remained practically unknown to the general public and spent most of his life in abject poverty.

His music is the subject of a similar paradox. More than half a century of composing saw his style change remarkably little; critical reaction, however, differed wildly. Some thought of him as an innovator where others considered him an arch-conservative. Some felt he was the heir to the great Germanic tradition, while others spoke of his Russian soul and his ability to capture in his music the atmosphere of Russia at the turn of the century. It would seem, then, that neither the composer’s personality nor his musical style can be analysed within the limits of a single tradition, be this even the rich tradition of a Russia or Germany. This ambivalence stems from Medtner’s own origins. Since Peter the Great had, in the words of Pushkin, ‘opened a window into Europe’, thousands of foreigners had been living in Russia. This strange community, which juxtaposed European roots with the changing environment of Russia, formed a unique part of Russian life and produced many remarkable figures—men of art, science and politics.

Medtner’s ancestors probably left Germany in the eighteenth century, and he was born in Moscow. Both his personality and his music evince a combination of Germanic tendency to weighty philosophizing and typically Moscovite spirit. The beginning of Medtner’s artistic activity came at a time which many consider to have been one of the high points in the history of Russian culture. This era is known as the Silver Age, or the Russian Renaissance. At the turn of the century the arts, music and philosophy were flourishing in Russia; the revolution of 1917 brought this unique period to an end. Like Scriabin and Rachmaninov, Medtner expressed the raw nerve of this momentous time: his contemporaries noted the ‘psychologically intense, demonic’ character of his music. Yet the composer used the ‘eternal laws of music’ alongside these more elusive, transient and indefinable principles. Much later, in 1930, in his book Muse and Mode he analysed with scientific precision the basic elements of the language of music (melody, harmony, rhythm), interpreting them in the spirit of the classical tradition of the nineteenth century and repudiating the whole development of modern music. Thus Medtner’s music is not easy to understand because of its complicated combination of entirely different elements: the fusion of German roots and Russian spirit, the quest for new musical expression and dedicated conservatism, a rare intelligence and almost childlike naïvety.

What was the genesis of Medtner’s style? He considered himself a follower of Beethoven and the best of his work reflects the great polyphonic skill, the detailed development of short compact motifs, and the severe spirit and concentrated depth of the late Beethoven sonatas. No less important for Medtner was German Romanticism in general and Schumann’s legacy in particular. Goethe (with whom Medtner’s great-grandfather was acquainted) was a permanent source of inspiration for him. Medtner was often compared with Brahms and there are indeed comparisons to be made: the deep seriousness of his music, some of the special harmonic features, the interest in intricate cross-rhythms, and piano-writing. Nevertheless, it would be a great mistake to consider him neo-Brahmsian. Medtner never imitated anybody and was, moreover, not noted for his interest in Brahms’s music. The similarities are rather the result of their independent development of the commonly inherited Romantic tradition.

Comparison of Medtner and Rachmaninov is more justifiable. They were great friends for most of their lives and they influenced each other in many ways. Medtner was enchanted by the beauty of Rachmaninov’s melodies and Rachmaninov was highly impressed by Medtner’s quest for new harmonies and rhythms. It is significant that Rachmaninov dedicated to Medtner his Fourth Piano Concerto, the most explicit instance of this mutual inspiration.

The best of Medtner’s music represents something very special, and it is unmistakable: the melodies and harmonies are inimitable in the way they are drawn from the piano, an instrument cherished by Medtner as much as by Chopin. Today, forty years after Medtner’s death, we see that the heroic, self-sacrificing work to which he devoted his whole life was not in vain. His music, imbued with the strength of his powerful spirit and the beauty he believed in, is discovering a new life.

Of the three Medtner piano concertos the first is remarkable for its inspirational inner content, the beauty of its melodies and the grand scale of its structure. It is probably his most outstanding work. He began it in 1914 and the first performance took place in Moscow on 12 May 1918, the composer as soloist under Koussevitsky.

The horrible events of the First World War are, perhaps unavoidably, reflected in the work. Russian and German cultures meant equally much to Medtner and the war between the two countries developed into a personal tragedy for him. The Concerto is a grandiose, one-movement construction, written in sonata form, where the extended development of each section compensates for the lack of the traditional division into movements. Slow and scherzo-like episodes sound almost like the middle movement of a symphony and the coda, which is thematically and dynamically rich, serves as a finale. The originality of the Concerto’s form is increased by the interfusion of two structural principles: the sonata form gives the work its general contours while the variation form imparts diversity, contrast and a more fragmentary structure.

The work opens with four introductory exclamations anticipating the appearance of the main theme, full of heroic yet tragic pathos. The thematic concentration of the Concerto’s musical material is remarkable: the main theme serves as the source for the two lyrical subjects, as well as for every other important section. The development is very unusual: it consists of a theme and a cycle of variations. Here the composer develops fragments of all the main themes of the Concerto with considerable polyphonic skill. The short recapitulation is extremely dynamic, and the coda presents the last climax of the Concerto. Medtner somewhat delays the outcome by leading the themes through a number of odd modulations and unusual harmonies: only at the very end do we hear a triumphant hymn in C major, followed by three final bell-like ringing strokes on the piano.

The Piano Quintet has a very special place among Medtner’s works. The composer himself regarded it as the synthesis or summary of all his work and, indeed, worked on it throughout his life. The first sketches date back to 1903/4 and it was only completed in 1949. This work, which was destined to be his last, combines freshness of inspiration with great mastery of composition.

Again, the structure of the Quintet is unusual. The first movement expresses what can only be described as a theme of Hope and Faith. It opens with a large introduction in which the epic theme flows broadly and solemnly. The new subject in the central section reminds one of the famous medieval tune Dies irae. The next and final part, the Maestoso, is essential to the whole being of the Quintet: here the composer introduces a motif which has deep autobiographical meaning. It is written as if to the words of the Gospel passage ‘Blessed are you who are hungry now; you will have your fill. Blessed are you who weep now; you will laugh for joy’. A coda combines the two themes ‘Dies irae’ and ‘Blessed’ in a manner reminiscent of bells.

The melody of the second movement is as beautiful and tragic as the words of the Psalm to which it was written (‘For your name’s sake, O Lord, you will pardon my guilt, great as it is’, and ‘Look toward me and have pity on me, for I am alone and afflicted’) and is deeply rooted in the ancient music of the Russian Orthodox Church. Gradually, the musical material in which fragments of the first movement can once more be heard flows into the ‘Blessed’ leitmotif, now sharply harmonized and distorted.

The Finale, following attacca, is the synthesis which sums up elements of the whole work; it lasts as long as the first two movements together, and is written in extremely complicated sonata form. The main conflict can be seen in the contrasts not only between the first and second subjects, but also between the exposition and development sections, which turn into a battlefield of multiple polyphonic combinations. The coda revives the second theme which the composer himself called ‘the Hymn’: this is an amazingly simple melody, full of light and rejoicing. Hyperion

Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951)

Piano Concerto No 1 in C minor Op 33 [34'05]

Piano Quintet in C major Op posth. [24'34]

Conductor – Alexander Lazarev

Piano – Dmitri Alexeev

Leader [Orchestra] – Stephen Bryant

Orchestra – BBC Symphony Orchestra

Performer – New Budapest Quartet

+ last month

FRANKIE "Half-Pint" JAXON — Complete Recorded Works In Chronological Order Volume 3 · 1937-1940 (1994) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

After cutting records with the Harlem Hamfats in Chicago during the years 1937 and 1938, Frankie "Half Pint" Jaxon made his final ...

.jpg)

.jpg)