The recent revival of York Bowen’s music, very much spearheaded by Hyperion, has spawned a plethora of new recordings of his compositions, and won him many new admirers. Among the new releases, this disc of Bowen’s piano sonatas is a uniquely important collection. It contains three premiere recordings, including two recordings of previously unpublished sonatas performed (with special permisson) from the manuscripts. It is thus the first ever recording of the complete sonatas – an unmissable opportunity for piano enthusiasts.

The recent revival of York Bowen’s music, very much spearheaded by Hyperion, has spawned a plethora of new recordings of his compositions, and won him many new admirers. Among the new releases, this disc of Bowen’s piano sonatas is a uniquely important collection. It contains three premiere recordings, including two recordings of previously unpublished sonatas performed (with special permisson) from the manuscripts. It is thus the first ever recording of the complete sonatas – an unmissable opportunity for piano enthusiasts.

Hyperion is delighted to welcome back the young virtuoso Danny Driver who was enthusiastically acclaimed for his masterly, stylish and technically dazzling performances of Bowen’s Third and Fourth Piano Concertos, and described as an ideal performer of these works. hyperion

YORK BOWEN (1884-1961)

Tracklist 1 :

1-4. Piano Sonata No. 1 In B Minor Op. 6

5-7. Piano Sonata No. 2 In C Sharp Minor Op. 9

8-9. Piano Sonata No. 3 In D Minor Op. 12

Tracklist 2 :

1-3. Short Sonata In C Sharp Minor Op. 35 No. 1

4-6. Piano Sonata No. 5 In F Minor Op. 72

7-10. Piano Sonata No. 6 In B Flat Minor Op. 160

Credits :

Piano – Danny Driver

Recorded In Henry Wood Hall, London England July 10-11, 2008 August 16-17. 2008.

Piano Steinway & Sons.

Notes in English, French & German.

Front illustration: Black Piano (2004) by Lincoln Seligman (b1950)

21.1.26

YORK BOWEN : The Piano Sonatas (Danny Driver) 2CD (2009) Two Version | FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

18.1.26

CÉSAR FRANCK : Piano Music (Stephen Hough) (1997) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

CÉSAR FRANCK (1822-1890)

1-3. Prélude, Choral Et Fugue M21 (1884)

4-6. Prélude, Aria Et Fugue M23 (1886/7)

7. Troisième Choral M40 (1890) 11:22

Adapted By [Transcribed By] – Stephen Hough

8. Danse Lente M22 (1885) 2:28

9. Grand Caprice M13 (Op 5, 1843) 13:43

10. Les Plaintes D'Une Poupée M20 (1865) 1:57

Piano [Steinway] – Stephen Hough

21.12.25

YORK BOWEN : Fragments from Hans Andersen · 12 Studies for piano (Nicolas Namoradze) Two Version | FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

Praised by Saint-Saëns as ‘the most remarkable of the young British composers,’ York Bowen (1884-1961) has all the same never received quite the attention his music deserves. This delightful disc is a treasure chest of lesser-known works given beautifully attentive performances from the acclaimed young pianist Nicolas Namoradze.

Bowen’s Fragments from Hans Andersen (1920) are ten musical vignettes, each capturing a scene or character inspired by the master of fairytales. Namoradze brings a deft touch to these charming works, teasing out their respective tenderness, melancholy and wit with subtlety and poise. The remainder of the disc is given over to a series of studies, all of which happily transcend the purely technical drill. The two brief Concert Studies (Op 9 No 2 and Op 32) are joyous, big-hearted works that demand considerable virtuosity but are nonetheless rich in melody. Namoradze conjures a splendid warmth and depth of sound throughout and is equally at home in the 12 Studies, Op 46 which follow. Not to be confused with Bowen’s celebrated 24 Preludes, Op 102, these studies do not adhere to the cycle of keys and each is labelled with a rather forbidding pedagogical title (‘for brilliance in passagework’, ‘to induce lateral freedom of hand and arm’), but they nonetheless hold together as a coherent work and Bowen himself performed the sequence in concert on occasion. Namoradze once more brings total technical assurance alongside exuberance and an unshowy sense of integrity to these fiendish pieces. An altogether enjoyable disc. hyperion

YORK BOWEN (1884-1961)

1-10. Fragments from Hans Andersen Op 58/61 [27'11

11. Concert study for piano No 1 in G flat major Op 9 No 2 [4'41]

12. Concert study for piano No 2 in F major Op 32 [3'07]

13-24. 12 Studies for piano Op 46 [31'22]

Nicolas Namoradze - Piano

Cover artwork: Piccadilly Circus by George Hyde Pownall (1876-1932)

21.7.25

STEPHEN HOUGH — Stephen Hough's Spanish Album (2006) Two Version | APE + FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

Stephen Hough’s latest solo album takes us on a colourful tour of Spain and all things Spanish: a kaleidoscope of slants and angles on the soul and character of a once exotic and remote country.

Antonio Soler (whose innumerable sonatas were considered sufficiently outlandish to earn him the sobriquet ‘the devil dressed as a monk’) sets the scene for a sequence of impressionist wonders by Granados, Albéniz and Mompou (a disc of whose pianistic micro-masterpieces—CDA66963—won for Stephen Hough the 1998 Gramophone Instrumental Award), and Federico Longas’s insinuatingly virtuosic charmer Aragón.

Hough then allows outsiders a view into the magical kingdom. Debussy and Ravel peer longingly over the Pyrenees, while Godowsky, Scharwenka, Niemann and finally Hough himself are all in turn unable to resist this richest of cultural experiences.

Stephen Hough’s esoteric recital CDs rapidly acquire something of a cult status. Classic CD wrote of Stephen Hough’s New Piano Album CDA67043: ‘This is a terrific disc. A master pianist reminds us that the piano can delight, surprise and enchant’; while Classic FM Magazine welcomed Stephen Hough’s English Album CDA67267 saying: ‘Hough’s pianism is a constant source of wonder—every chord and phrase perfectly judged’. Hyperion

The Spaniards

1. Sonata In F Sharp Major (Rubio Ed. No 90) 5:23

Composed By – Antonio Soler

2. Valses Poéticos 11:27

Composed By – Enrique Granados

3. Evocación (From Iberia Book I) 5:14

Composed By – Isaac Albéniz

4. Triana (From Iberia Book II) 5:12

Composed By – Isaac Albéniz

5. Pájaro Triste (From Impresiones Íntimas) 2:26

Composed By – Federico Mompou

6. La Barca (From Impresiones Íntimas) 1:25

Composed By – Federico Mompou

7. Secreto (From Impresiones Íntimas) 2:48

Composed By – Federico Mompou

8. Gitano (From Impresiones Íntimas) 2:53

Composed By – Federico Mompou

9. Aragon 4:39

Composed By – Federico Longas

The Frenchmen

10. La Soirée Dans Grenade (From Estampes) 5:23

Composed By – Claude Debussy

11. La Sérénade Interrompue (From Préludes Book I) 2:34

Composed By – Claude Debussy

12. La Puerta Del Vino (From Préludes Book II) 3:19

Composed By – Claude Debussy

13. Pièce En Forme De Habanera 2:38

Arranged By – Maurice Dumesnil

Composed By – Maurice Ravel

The Others

14. Tango 2:49

Arranged By – Leopold Godowsky

Composed By – Isaac Albéniz

15. Spanisches Ständchen Op 63 No 1 4:32

Composed By – Franz Xaver Scharwenka

16. Evening In Seville Op 55 No 2 3:34

Composed By – Walter Niemann

17. On Falla (2005) 4:43

Composed By – Stephen Hough

Credits :

Piano – Stephen Hough

Illustration [Front cover: 'Gazpacho' (Detail)] – Anthony Mastromatteo

9.7.25

RACHMANINOV : 24 Preludes (Steven Osborne) (2009) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

While there is much to admire in Steven Osborne's 2009 Hyperion recording of Rachmaninov's complete preludes, some fans of the composer may ultimately find themselves dissatisfied with his performances. Osborne is clearly a virtuoso with a wonderfully varied color palette and a way of balancing melody and harmony for maximum effectiveness There are some strong elements; his fleet fingers in the A flat major Prelude, his sumptuous sonorities in the C sharp minor Prelude, his galloping rhythms in the G minor Prelude, or his rolling left hand arpeggios in the B flat major Prelude, in addition to his overall command, control, and technique. Other listeners may question Osborne's feel for Rachmaninov's music. The restless melancholy of the B minor Prelude, the volatile passion of the F minor Prelude, and the spooky atmosphere of the G sharp minor Prelude are here, but to nowhere near the same degree as in other accounts of the pieces by veteran Rachmaninov pianists such as Vladimir Ashkenazy, where the music's hyper-Romantic emotional content is superbly expressed in wholly idiomatic performances. Hyperion's digital sound, though clear and colorful, is surprisingly a bit thin and a tad distant. James Leonard

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

1. Prelude In C Sharp Minor Op 3 No 2 (Lento) 4:51

2-11. Ten Preludes Op 23 (35:56)

12-24 Thirteen Preludes Op 32 (37:38)

Credits :

Piano – Steven Osborne

Front Illustration : Water Lilies (1895)] – Isaac Ilyich Levitan

16.4.25

ANTON RUBINSTEIN : Solo Piano Music (Leslie Howard) 2CD (1997) Dyad Series | APE (image+.cue), lossless

‘Warmly recommended’ (BBC Music Magazine)

‘Two exceedingly well-filled discs give us the cream of Rubinstein's piano music, beginning with the delicious Melody in F, his most famous composition’ (Classic CD)

«Les qualitées réclamées par Rubinstein sont comparables: panache, fougue, enthousiasme, puissance. Leslie Howard les possède à un haut degré. Il y a joint une délicatesse du toucher et une facilité pour un timbre moelleux qui font merveille dans les pages de caractère, alors qu'un rubato discret confère à la musique ce frémissent du coeur sans lequel il n'est pas de véritable romantisme» (Diapason, France) Reviews Hyperion

Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894)

CD1

1-2. Deux Mélodies Op 3 (1852) (7:05)

3-4. Deux Morceaux Op 30 (10:42)

5. Deuxième Barcarolle In A Minor, Op 45bis (1857) 6:32

6. Troisième Barcarolle In G Minor, Op 50 No 3bis (c1858) 3:43

7. Quatriéme Barcarolle In G Major (c1870) 5:11

8-11. Fantaisie In E Minor Op 77 (1866) (44:45)

CD2

1-3. Trois Caprices Op 21 (1855) (13:38)

4-6. Trois Sérénades Op 22 (1855) (19:42)

7-19. Thème Et Variations Op 88 (1871) (42:07)

Credits :

Piano – Leslie Howard

Cover artwork: Interior of the drawing room in the house of Baron Stieglitz in St Petersburg by Pyotr Fyodorovich Sokolov (c1787-1848)

3.4.25

ALKAN : Grande Sonate 'Les quatre âges' · Sonatine · Le Festin d'Ésope (Marc-André Hamelin) (1995) APE (image+.cue), lossless

The Grande Sonate and Sonatine, brought together on this recording, are Charles-Valentin Alkan’s first and last masterpieces for solo piano and illustrate two extremes in the composer’s aesthetic development.

The Grande Sonate and Sonatine, brought together on this recording, are Charles-Valentin Alkan’s first and last masterpieces for solo piano and illustrate two extremes in the composer’s aesthetic development.

In many respects, the Grande Sonate, Op 33, is one of the pinnacles not only of Alkan’s output but of the entire Romantic piano repertoire. In writing a piano sonata, Alkan was reviving and preserving a form which was not merely undervalued by the French but was even described by Schumann as being ‘worn out’. In the hands of this extremely discreet composer, it could almost claim to be a manifesto: composed in the wake of the 1848 Revolution, and dedicated to his father, it is prefaced by what constitutes one of the rare official examples of the composer’s taking an aesthetic stand on an extremely controversial matter: programme music. His text is not to be overlooked:

Much has been said and written about the limitations of expression through music. Without adopting this rule or that, without trying to resolve any of the vast questions raised by this or that system, I will simply say why I have given these four pieces such titles and why I have sometimes used terms which are simply never used by others.

It is not a question, here, of imitative music; even less so of music seeking its own justification, seeking to explain its particular effect or its validity, in a realm beyond the music itself. The first piece is a scherzo, the second an allegro, the third and fourth an andante and a largo; but each one corresponds, to my mind, to a given moment in time, to a specific frame of mind, a particular state of the imagination. Why should I not portray it? We will always have music in some form and it can but enhance our ability to express ourselves; the performer, without relinquishing anything of his individual sentiment, is inspired by the composer’s own ideas: a name and an object which in the realm of the intellect form a perfect combination, seem, when taken in a material sense, to clash with one another. So, however ambitious this information may seem at first glance, I believe that I might be better understood and better interpreted by including it here than I would be without it.

Let me also call upon Beethoven in his authority. We know that, towards the end of his career, this great man was working on a systematic catalogue of his major works. In it, he aimed to record the plan, memory or inspiration which gave rise to each one.

The composition and publication of the Grande Sonate occurred at a crucial moment in the composer’s life. During the summer of 1848, when the Revolution was not yet over, Zimmerman, Alkan’s teacher, resigned from his position as Professor of Piano at the Paris Conservatoire. It would seem natural enough that Charles-Valentin, his most brilliant and promising student, should succeed him; but in the troubled climate of the time, and as a result of some predictable intrigue, it was in fact a second-rate musician, Antoine Marmontel, who was to gain the post. This was a particularly bitter pill for Alkan to swallow; he was to fade gradually further into obscurity and renounce all public and official posts. The Revolution was also to harm any publicity which might have surrounded the publication of the Grande Sonate: although it was well heralded in the music magazines, it would appear that there was not one single review of the piece, nor one public performance thereafter. The British pianist Ronald Smith is fully justified in thinking that he brought the piece to life when he gave it its first public performance in America in 1973!

Alkan was to try his hand at the piano sonata form on four occasions: the Grande Sonate, Op 33, the Symphony and Concerto for solo piano, Op 39, and the Sonatine, Op 61, all illustrate the discrepancies between an inherited Classical form and the trends of Romanticism. The astonishing complexity of the Grande Sonate was certainly disconcerting for his contemporaries and sufficiently justified his decision to give the programme a preface. Let us not forget three of its most markedly original features: as in the Symphony and Concerto, Op 39, and well before Mahler or Nielsen, the tonality evolves during the course of the work without returning to a ‘root tonality’; confining ourselves to the start of each movement, the keys are respectively D major, D sharp minor, G major, G sharp minor; if we focus purely on the endings, we find B major, F sharp major, G major and G sharp minor. The sequence of tempi was equally likely to be disconcerting for the listener: in place of the usual quick–slow–quick, Alkan puts four successively slower movements one after another. Finally, he invokes two of the great Romantic myths – Faust and Prometheus; the first, immortalized by Goethe, enjoyed a popularity kept alive by Berlioz, Gounod, Liszt and Schumann etc, while Prometheus takes us back to antiquity, to an era which Alkan, being passionate about the Classics, knew well and which he often referred to in his compositions.

The sonata opens with ‘20 ans’, a frenzied scherzo which frequently reminds one of Chopin’s Scherzo No 3. Straightaway, the 3/4 time is juxtaposed with accents on every other beat. The trio portrays the awakening of love, working its way gradually through various sections, from ‘timidly’ to ‘lovingly’ and on to ‘with joy’. The coda brings the movement to a whirling conclusion.

‘30 ans, Quasi-Faust’ is the heart of the sonata. It opens with the Faust theme which, in four bars, covers the whole keyboard and states the rhythmic formulae which will permeate the entire movement. There follows the Devil’s theme, in B major, which is the inversion of Faust’s theme. Marguerite’s theme, in G sharp minor and then major, presented at first in a mood of sweet sadness, passes through numerous climatic changes. The development and the return of the exposition lead on to four huge arpeggios which spread across every octave of the keyboard. Now comes a fugue, a horribly complicated eight-part fugue, which the eye alone can follow in the score; in order to make it legible, the composer himself establishes the use of different manuscript styles! The fugue continues until the entrance of ‘Le Seigneur’, and the movement concludes with a clear victory of Good over Evil, thus inspired by Goethe’s Faust Part 2, unlike the ending of Berlioz’s opera-oratorio where the composer boldly damns his hero.

‘40 ans, un ménage heureux’ presents a picture of unspoken Romance, interrupted on two occasions by a charming three-voice digression entitled ‘les enfants’; this latter section exhibits a use of thirds, sixths, fifths which is very untypical of Alkan who, unlike Chopin, usually shows little interest in anything other than octaves and chords. With the return of the opening section, the theme, treated in canon, becomes even more animated. The clock striking ten is the signal for prayer.

‘50 ans, Prométhée enchaîné’ draws us to the abyss. As an epigraph, Alkan cites several verses of the Aesychlus tragedy:

No, you could never bear my suffering! If only destiny would let me die! To die … would release me from my torments! Would that Jupiter had not lost his power. I will live whatever he might do … See if I deserve to suffer such torments! [lines 750–754, 1051, 1091 (the end of the play)]

After the victory in ‘Quasi-Faust’ and the joy of the happy household – something which the composer would always be denied – ‘50 ans’ ends with an acknowledgement of failure, in a visionary piece written without hint of pomposity or excess. Thinking about the composer’s destiny, the piece is also a premonition.

The Sonatine, Op 61, was written fourteen years after the Grande Sonate and forms a striking contrast to it. Concise and concentrated in the extreme, refined in its style of writing, and of exceptional technical difficulty, it is a gem of equilibrium and perhaps presents Alkan at his most accessible. Its first movement, although swept along and interrupted by violent angry outbursts, maintains a profound coherence, reinforced by the taut conjoining of its two themes. The Allegramente which follows, in F major, belongs within the best tradition of Alkan’s falsely naive works. It is immediately reminiscent of the slow movement from Maurice Ravel’s Sonatine; Ravel was, moreover, familiar with the music of this, the composer of Le festin d’Esope. The Scherzo-Minuet, in D minor, is one of those perpetual motion pieces of which the composer was so fond; he interrupts its driving rhythm with a trio which eases the pace of the movement but is unsettled by various rhythmic and harmonic devices. The finale, Tempo giusto, opens with startling fifths which conjure up the empty chords of a cello or the toll of bells, in the style of Mussorgsky in his Pictures at an Exhibition; the sections which follow vary greatly without ever altering the movement’s deep cohesion. A dry fortissimo chord brings the four movements to a close.

Le festin d’Esope completes the cycle of 12 Études dans tous les tons mineurs, Op 39, to which the Symphony and the huge Concerto for solo piano belong. The term ‘study’ should be taken to mean the same as it does to Chopin and a fortiori Clementi or Cramer. Alkan, more so even than Liszt, expands the scope of this form to the dimension of a symphonic poem, a rhapsody. Le festin d’Esope consists of a series of variations on a theme which one might liken to traditional Jewish melodies. The argument is to be found again in Jean de la Fontaine’s La vie d’Esope le Phrygien:

One market day, Xantus, who had decided to treat some of his friends, ordered him to buy the best and nothing but the best. The Phrygian said to himself, ‘I’m going to teach you to specify what you want, without leaving it all to the discretion of a slave’. And so he bought nothing but tongue, which he adapted to each different sauce; the starter, the main course, the dessert, everything was tongue. At first the guests praised his choice of dish; but by the end they were filled with disgust. ‘Did I not order you’, said Xantus, ‘to buy the best?’ ‘And what could be better than tongue?’ answered Aesop. ‘It is our connection to civil life, the key to the sciences, the organ of truth and reason. Through it, we build and police our towns; we learn; we persuade; we rule over assemblies; we fulfil the greatest of all our duties, namely to praise God.’

The theme of the tongue, the most important organ and function, is frequently mentioned in the Bible, Alkan’s favourite book. The variations, apart from dealing with various technical problems, illustrate without doubt every possible transformation that a theme could go through; in addition, one is presented with a succession of little tableaux of the animal kingdom, Alkan giving us several hints of this such as the marking abajante.

The Barcarolle which completes this recital is taken from the third of Alkan’s five Recueils de Chants for piano. These five books are distinctive in that they are modelled on Mendelssohn’s first collection of Lieder ohne Worte; they follow the same tone sequence and conclude with a barcarolle. The Barcarolle from the third collection is undoubtedly one of Alkan’s most seductive and meaningful pieces: its melody imprints itself immediately on one’s memory, and the whole work radiates a melancholic sweetness. (François Luguenot - Hyperion)

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

1-4. Grande Sonate "Les Quatre Âges" Op 33 (38:25)

5-8. Sonatine Op 61 (17:56)

9. Barcarolle Op 65 No 6 3:53

10. Le Festin D'Esope Op 39 No 12 8:45

Credits :

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

Painting [Cover Painting] – Tiziano Vecellio

2.4.25

ALKAN : Concerto for solo piano · Troisième recueil de chants (Marc-André Hamelin) (2007) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Anyone familiar with the unfailing digits and seemingly inexhaustible energy of Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin would find the very prospect of his recording Charles-Valentin Alkan's giga-difficult Concerto for solo piano as a natural match of pianist and piece. This 50-minute mega-monstrosity -- the first movement alone lasts nearly a half an hour, and runs to more than 70 pages -- has been played only by pianists intrepid and skilled enough to make the voyage, the short list including Egon Petri, Alkan acolyte Ronald Smith, and John Ogdon, in one of his finest recorded outings. With Hamelin, this Hyperion release Alkan: Concerto for Solo Piano is all the more amazing as this is his second recorded traversal of the work, having done an earlier version for the Music & Arts label in 1993. What the 13-year interim has yielded is a deepening of Hamelin's interpretation, to the point where the rapid fire runs, leaping octaves, and thundering crescendos that characterize the work have become second nature and Hamelin is able to mainly concentrate on making Alkan's concerto sound like the glorious vision that it is. And that's not to mean the earlier recording was necessarily "bad," it's just that in the meantime he has achieved total independence from the technical challenge that Alkan's concerto represents.

This work is such a trip; it is a combination of symphony and concerto where all of the orchestral and solo parts are wound into just the two hands of the pianist. Apart from the first movement, it has a searing Adagio at its center and the Allegretto finale is marked alla barabaresca. As Brobdingnagian as the concerto is, however, Alkan never digresses; it is taut and completely strict in a formal sense even as it is likely the most expansive work for piano solo that the nineteenth century has to offer. Hamelin has mastered it, a feat so awesome that it almost makes one forget that the Hyperion disc also offers a late and lovely Alkan work as filler, the Third Book of the Recueil de Chants (1863), never before recorded in its entirety; Raymond Lewenthal recorded the Barcarolle alone on his groundbreaking RCA Victor LP Piano Music of Alkan in 1965. In a sense, Hyperion's Alkan: Concerto for solo piano illustrates how far we've come with Alkan in nearly five decades' time; from the enterprising, exploratory readings of Lewenthal in the 1960s to total command of Alkan's "impossible" pianist language in the 2000s. The one thing Alkan lacks is a place in the standard literature, and it doesn't appear as though he's ever going to have that, though if anyone can operate at the exalted level of advocacy that such a transition of thinking about Alkan would require, then Marc-André Hamelin is probably the man. Uncle Dave Lewis

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

1-3. Concerto For Solo Piano Op 39 Nos 8-10 (49:35)

4-9. Troisième Recueil De Chants Op 65 (17:57)

Credits :

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

Front illustration : The Kiss of the Vampire (1916) by Boleslas Biegas (1877-1954)

31.3.25

ALKAN : Esquisses, Op 63 (Steven Osborne) (2003) Two Version | APE & FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The renaissance of interest in the reclusive and eccentric 19th-century French composer Alkan has been one of the more interesting developments of the last part of the 20th century but it has usually been his massive and virtuoso works (the symphony and concerto for solo piano for example) which have made the biggest impression. Throughout his life though Alkan was also a miniaturist, as 25 Preludes and six books of Chants show, and this interest culminated in undoubtedly the greatest of these cycles, the Esquisses (sketches) here recorded. This set of 48 pieces plus a final Laus Deo runs through all 24 keys twice with the Laus Deo returning the double cycle to C major. A huge range of mood and colour is represented from simple folk song to etude, not forgetting the bizarre, as can be seen in the tone clusters of Les Diablotins or the schizophrenic Héraclite et Démocrite.

This cycle has only been recorded complete once before. With Steven Osborne applying his colour, virtuosity and interpretive insight we are confident we have produced a recording that will permanently raise the stature of these pieces in the musical world and add a significant milestone in the Alkan discography. Hyperion

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

1-12. 48 Esquisses Op 63 - Book I

13-24. 48 Esquisses Op 63 - Book II

25-36. Esquisses Op 63 - Book III

37-49. Esquisses Op 63 - Book IV

Credits :

Piano [Steinway & Sons], Liner Notes – Steven Osborne

Front Illustration : Hercules and the Hydra (detail) (1875/6) by – Gustave Moreau (1826-1898)%20-%20back.png)

ALKAN : Symphony for solo piano • Trois Morceaux dans le genre pathétique (Marc-André Hamelin) (2001) APE (image+.cue), lossless

Marc-André Hamelin's first solo Alkan recording (CDA66794) met with the most superlative critical reception imaginable (culminating in Fanfare magazine's "one of the best releases of anything to have been made, a classic of the recorded era"). This follow-up proves to be no less spectacular.

The disc is framed by two of the 'monster' works for which Alkan is notorious. The four movements of the Symphony for solo piano are taken from his magnum opus, the 12 Studies in the minor keys Op 39. This piece has become one of Alkan's best known but never has its finale (once described as a 'ride in hell') been so spectacularly thrown off. The Trois Morceaux dans le genre pathétique are the earliest pieces in which Alkan's true personal style became apparent. These are three massive studies each with programmatic titles and an atmosphere of Gothic horror that requires a supreme virtuoso to tackle their outlandish technical demands. This is their first recording.

The recital is completed by three pieces of rather religious inspiration. While their scale and technical demands are those of a more conventional composer, their quirky sound-world and often sardonic mood confirm the composer as our reclusive Frenchman. Hyperion

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

1-4. Symphony For Solo Piano Op 39 Nos 4-7 (26:06)

5. Salut, Cendre Du Pauvre! Op 45 (8:40)

6. Alleluia Op 25 (2:40)

7. Super Flumina Babylonis Op 52 (Paraphrase Du Psaume 137) (6:30)

8-10. Souvenirs: Trois Morceaux Dans Le Genre Pathétique Op 15 (29:56)

Credits:

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

Illustration [Front Illustration: 'The Ballad Of Lenore, Or 'The Dead Go Fast'' (1839) – Horace Vernet

28.3.25

LEO ORNSTEIN : Suicide In An Airplane · Danse Sauvage · Sonata 8 And Other Piano Music (Marc-André Hamelin) (2002) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

When Leo Ornstein died in February 2002, the musical world lost a fascinating composer, quite possibly the oldest of all time (the year of his birth is uncertain, but he was probably 109 years old). Ornstein had an extraordinary life: he was a child-prodigy pianist in his native Russia, a refugee from anti-Semitism, an avant garde American composer and a virtuoso pianist of international renown in his early twenties. However, at the height of his fame he voluntarily turned his back on the limelight and took sanctuary in increasing obscurity, and having been almost entirely forgotten, he lived long enough to take satisfaction in the re-emergence of an interest in his music—of which this CD is early testimony.

When Leo Ornstein died in February 2002, the musical world lost a fascinating composer, quite possibly the oldest of all time (the year of his birth is uncertain, but he was probably 109 years old). Ornstein had an extraordinary life: he was a child-prodigy pianist in his native Russia, a refugee from anti-Semitism, an avant garde American composer and a virtuoso pianist of international renown in his early twenties. However, at the height of his fame he voluntarily turned his back on the limelight and took sanctuary in increasing obscurity, and having been almost entirely forgotten, he lived long enough to take satisfaction in the re-emergence of an interest in his music—of which this CD is early testimony.

Ornstein's early piano works were unlike anything else in music. He employed the piano as a percussion instrument, pounding out savage rhythms and ferocious cluster-chords with a raw primal energy. He embraced atonality independently of Schoenberg and rhythmic primitivism unaware of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring. The titles of his pieces—among them Danse sauvage and Suicide in an Airplane—reflected the extremist brutality of the music and rapidly gained him notoriety. By his early twenties he was one of the most highly reputed of contemporary composers.

The music on this CD comes from each end of Ornstein's improbably long creative career. The shorter works were written at its outset, while the large-scale, kaleidoscopic Eighth Piano Sonata, his last composition, was finished in September 1990, when he was in his late nineties.

The ever-inquisitive Marc-André Hamelin gives commanding performances of these supremely demanding works. The result is a stunning disc that reveals one of the twentieth century's most original and quirkily imaginative creative minds. Hyperion

Leo Ornstein (1892-2002)

1. Suicide In An Airplane (3:46)

2. À La Chinoise (4:59)

3. Danse Sauvage (2:48)

4-13. Poems Of 1917 (17:03)

14-22. Arabesques, Op. 42 (10:22)

23. Impressions De La Tamise (7:57)

24-29. Piano Sonata No. 8 (30:12)

Credits :

Painting – Monika Giller-Lenz

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

23.3.25

JOHANN QUANTZ : Flute Concertos (Rachel Brown · The Brandenburg Consort · Roy Goodman) (1997) Two Version | FLAC (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

Quantz owes his current neglect in the concert hall and recording catalogue to a somewhat perverse fact of history: he was by far the most highly paid musician of his day (earning seven times as much as C P E Bach, for example) and yet his patronage from Frederick the Great—he was truly an 'exclusive artist'—meant that none of his works was published, all remaining in the monarch's private collection.

Today his prolific output (there are some 300 flute concertos alone) is gradually being resurrected, these delightful works being recognized for their true worth. Quantz's own virtuosic skills on the flute, coupled with several drastic innovations he made to flute design and construction, make for works which push the Baroque instrument to the very limits of feasibility. Hyperion

Johann Quantz (1697-1773)

1-3 Concerto In A Major No. 256 17:25

4-7 Concerto In B Minor No. 5 14:16

8-10 Concerto In C Minor No. 216 16:29

11-13 Concerto In G Major No. 29 11:58

14-16 Concerto In G Minor No. 290 15:36

Credits

Flute, Soloist – Rachel Brown

Directed By [From The Fortepiano And Harpsichord] – Roy Goodman

Orchestra – The Brandenburg Consort

Illustration [Front Illustration] – Cornelis Troost

4.9.24

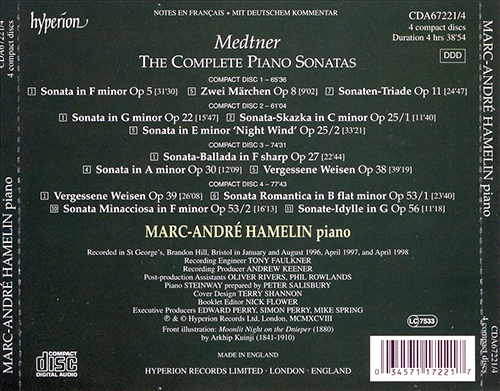

MEDTNER : The Complete Piano Sonatas · Forgotten Melodies I - II (Marc-André Hamelin) 4xCD (1998) APE (tracks), lossless

'I repeat what I said to you back in Russia: you are, in my opinion, the greatest composer of our time.' – Sergei Rachmaninov (1921)

'I repeat what I said to you back in Russia: you are, in my opinion, the greatest composer of our time.' – Sergei Rachmaninov (1921)

It would be hard to overestimate the importance of this set.

Medtner's piano compositions are arguably the last area of great Romantic piano repertoire to be discovered. His music is difficult, both technically and intellectually, and does not 'play to the gallery', which may explain its neglect. But once his world has been entered it proves endlessly fascinating and compelling, his work growing in stature with every hearing until one is left in no doubt as to its overwhelming effect.

Central to his output are the 14 Piano Sonatas (though the title covers a multitude of structures and sizes) and here for the first time we have the complete cycle recorded by one artist. Hyperion Tracklist & Credits :

BUSONI : Late Piano Music (Marc-André Hamelin) 3CD (2013) FLAC (image+.cue) lossless

The late piano works of Ferruccio Busoni can be characterized as virtuoso music par excellence, and because of their contrapuntal complexity, harmonic density, and technical difficulty, these pieces can have no greater champion than Marc-André Hamelin, the virtuoso's virtuoso. This Hyperion set of three CDs presents music that is far from well-known, and its obscurity adds another layer of unnecessary mystery. However, Hamelin is just the artist to sweep that all aside and present these seldom played pieces with clarity, precision, and élan to make them truly impressive. Busoni's music transcends any fixed style and is more than pastiche, though much of his work shows the influence of J.S. Bach, whose music Busoni frequently adapted for the modern piano and found to be a constant source of inspiration. Additionally, Busoni was a leader in the development of pantonal music, which is often confused with atonality, and worked out various ideas he described in his book, The Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music. Hamelin is perhaps the best guide to the complicated world of Busoni, and thanks to his astonishing playing, this music communicates more directly and powerfully than many other attempts by other pianists. Hyperion's recording is clear and reasonably close to the piano, so virtually every note can be heard. Blair Sanderson

The late piano works of Ferruccio Busoni can be characterized as virtuoso music par excellence, and because of their contrapuntal complexity, harmonic density, and technical difficulty, these pieces can have no greater champion than Marc-André Hamelin, the virtuoso's virtuoso. This Hyperion set of three CDs presents music that is far from well-known, and its obscurity adds another layer of unnecessary mystery. However, Hamelin is just the artist to sweep that all aside and present these seldom played pieces with clarity, precision, and élan to make them truly impressive. Busoni's music transcends any fixed style and is more than pastiche, though much of his work shows the influence of J.S. Bach, whose music Busoni frequently adapted for the modern piano and found to be a constant source of inspiration. Additionally, Busoni was a leader in the development of pantonal music, which is often confused with atonality, and worked out various ideas he described in his book, The Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music. Hamelin is perhaps the best guide to the complicated world of Busoni, and thanks to his astonishing playing, this music communicates more directly and powerfully than many other attempts by other pianists. Hyperion's recording is clear and reasonably close to the piano, so virtually every note can be heard. Blair Sanderson

Tracklist & Credits :

28.8.24

CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL Bach : Sonatas & Rondos (Marc-André Hamelin) 2CD (2022) FLAC (image+.cue) lossless

The music of C P E Bach makes complex stylistic demands of the performer like little else of its time, the extraordinary drama and intensity tempered by Enlightenment elegance and the influence of the Baroque. Marc-André Hamelin’s performances set new standards in this endlessly absorbing repertoire. hyperion-records.co.uk Tracklist & Credits :

The music of C P E Bach makes complex stylistic demands of the performer like little else of its time, the extraordinary drama and intensity tempered by Enlightenment elegance and the influence of the Baroque. Marc-André Hamelin’s performances set new standards in this endlessly absorbing repertoire. hyperion-records.co.uk Tracklist & Credits :

24.8.24

АRENSKY : Piano Music (Stephen Coombs) (2011) Serie Russian Piano Portraits | FLAC (image+.cue) lossless

Stephen Coombs's 'Russian Piano Portraits' series turns its attention to solo piano music by Anton Arensky, one of the more shadowy figures of the Russian pianistic pantheon. Bon viveur extraordinaire, Arensky lived life in Moscow to the full—and to the disgust of colleagues such as Rimsky-Korsakov—but he was also an important teacher whose pupils included Rachmaninov, Scriabin, Glière and Grechaninov. Indeed, it was Arensky, together with Taneyev (successor to Rubinstein as director of the Moscow Conservatory), who shaped a situation in 1880s Moscow which finally allowed the city to rival St Petersburg in terms of its musical culture.

Arensky's piano pieces have an easy charm and lyrical breadth of melodic invention. They also show rare inventiveness. There is a quality that is both nostalgic and surprising, reassuringly familiar yet unconventional in harmonic and melodic construction. This music has the power to move the emotions, not perhaps in a dramatic or passionate way, but by its rather personal reflective quality. hyperion-records.co.uk Tracklist & Credits :

14.8.24

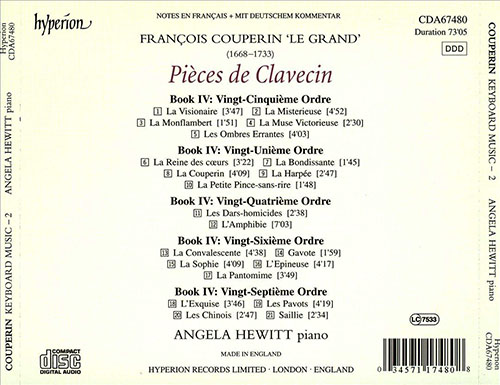

FRANÇOIS COUPERIN : Keyboard Music • 2 (Angela Hewitt) (2003) APE (image+.cue), lossless

Angela Hewitt once again presents an intelligent, yet eminently musical

performance of Baroque keyboard works on the piano on the second of her

three discs devoted to Couperin's Pieces de Clavecin. Her depth of

knowledge, revealed in her liner notes, extends from the works to his

life, his times, and Baroque music. This can be heard in her playing,

adding to her own enjoyment of the pieces. She obviously enjoys the

challenges of interpreting then presenting the pictures Couperin hints

at with titles such as Les Ombres errantes (The Wandering Souls), La

Sophie (either a Muslim mystic or the name of a young girl), and Saillie

(either a leap or a quip), and of performing them on a modern version

of an instrument that had only just been invented when these were

written and, therefore, is not the instrument Couperin anticipated being

used. On this particular disc, the works primarily use the upper part

of the keyboard. Hewitt has a touch that is neither too heavy for this,

which would make them sound dense or even muddy, nor too delicate, which

would make them seem more ephemeral or trifling. Nor does she ever try

to approximate the sounds of a harpsichord. She gives each piece

beautifully clear tones and phrasing. Her presentation and her

understanding make the disc a thoroughly enjoyable experience. Patsy Morita

Tracklist & Credits :

FRANÇOIS COUPERIN : Keyboard Music • 3 (Angela Hewitt) (2005) APE (image+.cue), lossless

With this disc, Angela Hewitt, the renowned Canadian pianist who heretofore specialized in the keyboard music of Bach, completes her survey of the keyboard music of François Couperin. While it is a highly selective survey -- Hewitt chose the works based on how well she thought the harpsichord works might sound on the modern concert grand and on her own personal interest -- it is also a highly significant survey. Because while Bach's harpsichord music is standard repertoire for most pianists, Couperin's harpsichord music has remained terra incognito for nearly all pianists and Hewitt's marvelously apt and wonderfully balanced performances go a long way toward providing the proof that the music can sound equally delightful on the piano. With all the Third Suite and much of the Fourth Suite from Couperin's Third Book of Pièces de Clavecin plus 10 movements chosen from the first and second books, Hewitt's selections are all highly effective and sound as natural on the piano as they do on the harpsichord. Purists may disparage the whole notion of playing harpsichord music on the piano, but even they will have to admit that Hewitt's warmly modulated tone and virtually flawless technique make for lovely listening. Hyperion's sound is perhaps just a bit too distant, but never less than clear and deep. James Leonard Tracklist & Credits :

With this disc, Angela Hewitt, the renowned Canadian pianist who heretofore specialized in the keyboard music of Bach, completes her survey of the keyboard music of François Couperin. While it is a highly selective survey -- Hewitt chose the works based on how well she thought the harpsichord works might sound on the modern concert grand and on her own personal interest -- it is also a highly significant survey. Because while Bach's harpsichord music is standard repertoire for most pianists, Couperin's harpsichord music has remained terra incognito for nearly all pianists and Hewitt's marvelously apt and wonderfully balanced performances go a long way toward providing the proof that the music can sound equally delightful on the piano. With all the Third Suite and much of the Fourth Suite from Couperin's Third Book of Pièces de Clavecin plus 10 movements chosen from the first and second books, Hewitt's selections are all highly effective and sound as natural on the piano as they do on the harpsichord. Purists may disparage the whole notion of playing harpsichord music on the piano, but even they will have to admit that Hewitt's warmly modulated tone and virtually flawless technique make for lovely listening. Hyperion's sound is perhaps just a bit too distant, but never less than clear and deep. James Leonard Tracklist & Credits :

12.8.24

MENDELSSOHN : Songs and Duets (Sophie Daneman • Nathan Berg • Eugene Asti) (1998) FLAC (image+.cue) lossless

The latest research indicates that at least one hundred-and-six lieder, thirteen vocal duets and sixty part-songs by Mendelssohn have survived. Yet even during an age characterized by an apparently insatiable desire for the musically obscure and neglected, these impeccably crafted microcosms are rarely encountered in the concert hall where Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and Wolf (even Liszt by musical association) continue to form the backbone of the Austro-German Romantic lieder tradition.

The latest research indicates that at least one hundred-and-six lieder, thirteen vocal duets and sixty part-songs by Mendelssohn have survived. Yet even during an age characterized by an apparently insatiable desire for the musically obscure and neglected, these impeccably crafted microcosms are rarely encountered in the concert hall where Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and Wolf (even Liszt by musical association) continue to form the backbone of the Austro-German Romantic lieder tradition.

The main reason for this neglect is Mendelssohn's comparatively narrow emotional range. Whereas the aforementioned composers all fearlessly probed the dark side of the human psyche, for the peaceable, broadly contented and self-contained Mendelssohn such concerns simply lay outside his experience. Equally, his songs were above all intended to be sung and enjoyed around the piano at home rather than subjected to public scrutiny. It is hardly Mendelssohn's fault that (with the notable exception of Mozart) commentators generally share an irrational tendency to upgrade the value of music in which laughter emerges only through tears rather than the other way round. Hyperion Tracklist & Credits :

+ last month

BUMBLE BEE SLIM — Complete Recorded Works In Chronological Order Volume 5 · 1935-1936 | DOCD-5265 (1994) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

Tracklist : 1. Shelley Armstrong– How Long How Long Blues 2:53 2. Shelley Armstrong– You Don't Mean Me No Good 2:43 3....

%20-%20front(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)