Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

1-4. Rapsodie Espagnole (16:05)

5. Introduction And Allegro 10:19

6. Entre Cloches (From Sites Auriculaires) 2:54

7. Shéhérazade (Ouverture De Féerie) 13:10

8. Frontispice (For Five Hands) 1:43

9. La Valse (Poème Choreographique Pour Orchestre) 11:33

Credits :

Piano – Christopher Scott, Stephen Coombs

21.7.25

RAVEL : Music for Two Pianos (Stephen Coombs & Christopher Scott) (2011) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

24.8.24

АRENSKY : Piano Music (Stephen Coombs) (2011) Serie Russian Piano Portraits | FLAC (image+.cue) lossless

Stephen Coombs's 'Russian Piano Portraits' series turns its attention to solo piano music by Anton Arensky, one of the more shadowy figures of the Russian pianistic pantheon. Bon viveur extraordinaire, Arensky lived life in Moscow to the full—and to the disgust of colleagues such as Rimsky-Korsakov—but he was also an important teacher whose pupils included Rachmaninov, Scriabin, Glière and Grechaninov. Indeed, it was Arensky, together with Taneyev (successor to Rubinstein as director of the Moscow Conservatory), who shaped a situation in 1880s Moscow which finally allowed the city to rival St Petersburg in terms of its musical culture.

Arensky's piano pieces have an easy charm and lyrical breadth of melodic invention. They also show rare inventiveness. There is a quality that is both nostalgic and surprising, reassuringly familiar yet unconventional in harmonic and melodic construction. This music has the power to move the emotions, not perhaps in a dramatic or passionate way, but by its rather personal reflective quality. hyperion-records.co.uk Tracklist & Credits :

16.1.22

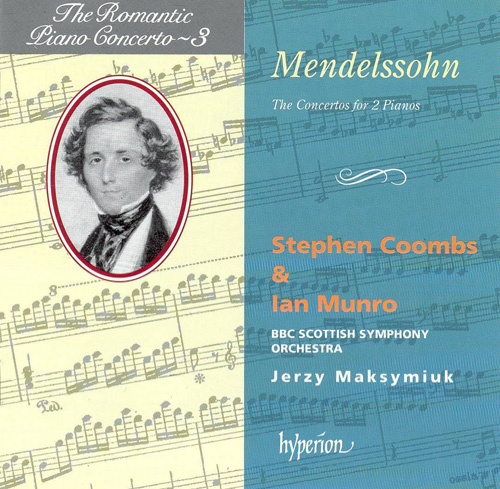

MENDELSSOHN : The Concertos For 2 Pianos (Ian Munro, Stephen Coombs · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Jerzy Maksymiuk) (1992) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 3 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Mendelssohn was an exceptionally gifted pianist, whose early studies under Ludwig Berger progressed at an astonishing rate. After hearing a recital given at home by the twelve-year-old boy, Goethe exclaimed: ‘What this little man is capable of in terms of improvisation and sight-reading is simply prodigious. I would have not thought it possible at such an age.’ When a companion reminded him that he had heard Mozart extemporize at a similar age, the great poet replied: ‘Just so!’ This was in 1821, by which time Mendelssohn had already composed a violin sonata, three piano sonatas, and two operas!

Mendelssohn’s mature piano style was derived not so much from the orchestral texturing of Beethoven and Schubert, as from the filigree intricacies of the German virtuoso piano school, represented principally by Hummel and Weber, further enhanced by a Mozartian emphasis on textural clarity. It was never Mendelssohn’s intention to push contemporary keyboard instruments beyond that of which they were comfortably capable, more to utilize those qualities for which they were best adapted—brilliant clarity in the treble register, and the ability to sustain a flowing, cantabile melody without undue bass resonance.

Mendelssohn’s first surviving works in concerto form date from 1822: the D minor Violin Concerto (not the popular E minor, a much later composition) and the Piano Concerto in A minor, both with string orchestra accompaniment, closely followed by a D minor Concerto for violin, piano and strings in May 1823. The Concertos for two pianos also belong to this early group, the E major being dated 17 October 1823, and the A flat major 12 November 1824. Both works had entirely dropped out of the repertoire until, in 1950, the original manuscripts were ‘rediscovered’ in the Berlin State Library.

Mendelssohn’s sister, Fanny, was also a gifted pianist, and it is almost certain that the E major Concerto was written with her in mind. However, it also appears likely that the A flat Concerto was inspired by Felix’s first encounter with the young piano virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles. Upon seeing the boy Mendelssohn play, even Moscheles could barely believe his eyes: ‘Felix, a mere boy of fifteen, is a phenomenon. What are all other prodigies compared with him?—mere gifted children. I had to play a good deal, when all I really wanted to do was to hear him and look at his compositions.’

The major criticism levelled at the Two-Piano Concertos is their tendency to overstretch relatively fragile musical material, as, with two soloists to contend with, Mendelssohn had been keen to ensure that the music was shared equally, thus involving an unusual amount of repetition. It would hardly be fair to expect even Mendelssohn to have achieved the miraculous thematic concision and structural cohesion of the E minor Violin Concerto and G and D minor Piano Concertos at such an early age.

The opening tutti of the E major Concerto uncovers a vein of dream-like contentment which was to become Mendelssohn’s expressive trademark. Virtually every subsequent composition contains passages of this nature contrasted, as here, by fleet-footed music of quicksilver brilliance. Even the use of Mozartian falling chromaticisms fails to cloud the blissfully trouble-free outlook.

The central 6/8 Adagio anticipates Mendelssohn’s favourite arioso Lieder ohne Worte style, whilst the high velocity finale demonstrates the composer’s precocious ability to assimilate Hummelian semiquaver athletics, and organize them into a convincing (if not yet fully developed) structure, transcending the aimless note-spinning of many of his older contemporaries.

The first movement of the A flat major Two-Piano Concerto is Mendelssohn’s longest concerto movement, and despite the composer’s declared preference for the E major Concerto, it displays a greater awareness of internal balance and structural proportions than its younger companion. The Mozartian opening theme (shades of the A major Concerto K414!) is embellished by some decidedly un-Mozartian virtuoso cascades during the soloists’ exposition, although a second lyrical idea is decidedly more restrained in its pyrotechnical aspirations.

The wistful Andante is clearly premonitory of the main theme of the G minor Piano Concerto’s slow movement, even if the continually flowing 6/8 metre and self-conscious virtuoso flourishes betray a certain lack of formal confidence in comparison with the later work.

Weber clearly marks the starting point for the good-natured Allegro vivace finale, its jocular high spirits being effectively contained by passing moments of mild contrapuntal ingenuity. The exuberant coda forces the main theme into overdrive, betraying a refreshingly boyish naivety, in stark contrast to the startling individuality and resourcefulness of the work as a whole. At only fifteen yeary of age, Mendelssohn was no mere fledgling composer but a highly creative intelligence on the verge of artistic maturity. Hyperion

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Concerto for two pianos in A flat major[41'28]

Concerto for two pianos in E major[30'35]

Credits :

Conductor – Jerzy Maksymiuk

Leader – Geoffrey Trabichoff

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Ian Munro, Stephen Coombs

ARENSKY : Piano Concerto In F Minor, Op 2 • Fantasia On Russian Folksongs, Op 48 ♦ BORTKIEWICZ : Piano Concerto No 1 In B Flat, Op 16 (Stephen Coombs · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Jerzy Maksymiuk) (1993) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 4 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Anton Stepanovich Arensky and Sergei Eduardovich Bortkiewicz are hardly household names. Arensky’s delicious Piano Trio in D minor continues to keep its place on the fringes of the chamber repertoire, and the Waltz movement from his Suite for two pianos receives an occasional outing; otherwise nothing. Who has even heard of Bortkiewicz other than aficionados of the piano’s dustier repertoire?

Anton Stepanovich Arensky and Sergei Eduardovich Bortkiewicz are hardly household names. Arensky’s delicious Piano Trio in D minor continues to keep its place on the fringes of the chamber repertoire, and the Waltz movement from his Suite for two pianos receives an occasional outing; otherwise nothing. Who has even heard of Bortkiewicz other than aficionados of the piano’s dustier repertoire?

Arensky was born in 1861 in Novgorod, a birthplace shared with Balakirev whose influence on the course of his country’s music during the second part of the nineteenth century was more profound than any other. Arensky, born a generation later and without the same musical genius and aggressive nationalism, fell under the spell of the post-Chopin/Liszt school (both composers revered by Balakirev and his nationalist ‘Free School’ of music). He was not going to extend the piano’s expressive potential as the mightier talents of Scriabin, Medtner and Rachmaninov were later to do.

Arensky’s gifts were, nevertheless, precocious. By the age of nine he had already composed some songs and piano pieces. His father (a doctor and accomplished amateur cellist) and mother (her son’s first teacher and an excellent pianist herself) moved to St Petersburg and the boy entered the Conservatory there in 1879, graduating in 1882, a year after writing the present Piano Concerto.

Arensky’s Opus 2 is unmistakably indebted to Chopin and Tchaikovsky, with the melodic grace of Mendelssohn and some of the more virtuosic passages of Liszt thrown in for good measure. (The last movement threatens to break into the opening of Grieg’s Piano Concerto!) Indeed, after hearing the work for the very first time, the listener somehow feels that he knows it intimately, like an old friend … undemanding, and for whom one has to make no special effort.

It’s a cosy piece, full of hummable tunes. As one would expect of a composition pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov, it is expertly crafted and the piano part is distinctive and beautifully laid out. The most daring departure from convention is in the use of a 5/4 time signature in the Finale. It was a quirk of Arensky’s that he enjoyed unusual metres. (Tchaikovsky even reproached him for doing so.)

The Concerto captured the imagination of many pianists of the day—it was a favourite of the youthful Vladimir Horowitz—and it provided an effective and stylish vehicle for many a barn-stormer before its salon prettiness came to be seen as superficial and second-rate. Arensky dedicated the work to the great cellist ‘Herrn Professor Carl Davidoff’ [sic], head of the St Petersburg Conservatory during the time the composer studied there. It was a dedication repeated when he composed his celebrated Trio in Davidov’s memory.

The Concerto was published in 1883 and was an immediate success in both St Petersburg and Moscow. The composer, having won the Gold Medal for composition with his Symphony No 1 in B minor, was appointed Professor of Harmony and Counterpoint at the Moscow Conservatory. A successful if not adventurous career would seem to have been presaged by these youthful triumphs. Not only this, but he was befriended and championed by Tchaikovsky. A product of the Nationalist school of St Petersburg and now a star on the staff of the more international Moscow establishment, Arensky continued to compose prolifically as well as teach (Rachmaninov, Scriabin and Gretchaninov were among his pupils) until 1894. He resigned his post on being offered the directorship of the Imperial Court Chapel in succession to Balakirev himself, no less, who recommended Arensky for the position. This involved a move back to St Petersburg and it is significant that the other composition of Arensky’s presented here dates from 1899 and is, again, a product of his life in the city headquarters of the Russian nationalist school: Russian themes in a cosmopolitan wrapping.

The Fantasy on Russian folksongs, Opus 48, is a brief but attractive rhapsody using two folk tunes collected by the ethno-musicological pioneer Trophim Ryabinin. The first (Andante sostenuto) is in E minor; the second (Allegretto) in D minor. Slight though the piece may be, it makes for a pleasant listen on disc, for in what concert hall does one now hear this kind of piano-and-orchestra lollipop?

The directorship of the Imperial Chapel provided not only a handsome salary but also a lifetime pension of 6,000 roubles a year for Arensky. Underneath this apparently ordinary story of modest acclaim and success, however, there ran a dark and troubled (though typically Russian) streak. Arensky, from very early in his career, was an alcoholic and an inveterate gambler. Moreover, his private life remains a mystery. He never married and elected to receive few visitors—an austere and unexpected contrast to the genial, expressive lyricism of his attractive music. He died of consumption in a sanatorium in Finland in February 1906.

The Bortkiewicz Concerto has been recorded once before, albeit in a heavily cut version. This Hyperion issue is therefore a premiere recording of the complete work. The American pianist Marjorie Mitchell made several out-of-the-way concerto discs with the conductor William Strickland in the late 1950s and early ’60s, those by Carpenter, Field, Delius and Britten among them. Her recording of the Bortkiewicz Concerto was coupled with Busoni’s Indian Fantasy! That Brunswick disc has acquired something of a legendary status among collectors (it is extremely hard to come by) because Bortkiewicz’s Piano Concerto No 1 is one of the great ‘fun’ concertos with its heady bravura writing, lush orchestration, strong, well-wrought and effective material and, in the first movement, one of the most seductive, romantic themes of the whole genre. Hollywood never had it this good—close your eyes and black-and-white films of lost love, heartache and yearning passion are conjured up. If the other two movements are less successful they are only slightly so; the second is a gorgeously tuneful Andante, the Finale a Russian dance. Chronologically, of course, Hollywood has nothing to do with Bortkiewicz and his First Concerto. Dedicated to his wife, the work was premiered in 1912 (and published the following year), after which it was taken up enthusiastically.

Like Arensky, Bortkiewicz was Russian (he was born in Kharkov, 16 February 1877) and studied at the St Petersburg Conservatory—in his spare time at first, for his father insisted that he study law. ‘I inherited my mother’s pleasure in music-making’, he wrote. ‘And what a blessing it was that we made much music when I was young. My mother played the piano very well and I was passionately fond of music.’

Later, from 1900 to 1902, he studied at the Leipzig Conservatory—piano with the former Liszt pupil Alfred Reisenauer (1863–1907), and composition with Salomon Jadassohn (1831–1902), another erstwhile Liszt student and among the most celebrated German pedagogues of the time, famously arch-conservative in his codified views on harmony and counterpoint.

Unlike some of his Russian contemporaries (Rachmaninov, Medtner, Scriabin) Bortkiewicz was not a sufficiently gifted pianist to make a career as a soloist, though after his debut (Munich, 1902) he made several European tours. He made no records or piano rolls and while one critic felt he produced a ‘harsh, jarring sound’ others give the impression of him being only a capable player, at his best in his own works. His strengths, he eventually decided, were teaching and composition. He taught at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory in Berlin from 1904 until the outbreak of the First World War when he was forced to return to Russia. After the Revolution he left his native land, like so many never to return again, and after a peripatetic existence, including a two-year stay in (then) Constantinople, Bortkiewicz finally settled in Vienna in 1922, dying there in October 1952.

‘I am a Romantic and a melodist’, he wrote in an essay towards the end of his life, ‘and as such and in spite of my distaste for the so-called ‘modern’, atonal and cacophonic music, I do hope that I composed some noteworthy works without getting the reputation of being an epigone or imitator of composers who lived before me.’ Bortkiewicz’s compositions are dominated by those for his instrument and many are well worth investigating (Lamentations and Consolations, Op 17, for example, and some of the Preludes from Opp 13, 15, 33 and 40, Lyrica Nova Op 59 from 1940, and the 1907 Piano Sonata No 1 in B major, Op 9). Perhaps, like the present Concerto (he wrote two others), they lack profundity and originality in the widest sense. But does the only music we appreciate have to be by the great composers who overturned systems, struck out for the unknown, and challenged their muse? One hopes not. There must always be a place for those like Arensky and Bortkiewicz who reflect so elegantly and expertly on what has gone before, rather than shake us by the ears and grab us (sometimes screaming) into the future. Hyperion

Anton Arensky (1861-1906)

Piano Concerto in F minor Op 2 [25'35]

Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877-1952)

Piano Concerto No 1 in B flat major Op 16 [35'34]

Credits :

Conductor – Jerzy Maksymiuk

Leader – Geoffrey Trabichoff

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Stephen Coombs

GLAZUNOV : Piano Concerto No 1 In F Minor • Piano Concerto No 2 In B Major ♦ GOEDICKE : Concertstück Op 11 (First Recording) (Stephen Coombs · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Martyn Brabbins) (1996) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 13 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The disc is the thirteenth volume in the famous Hyperion 'Romantic Piano Concerto' series; it also follows on from Stephen Coombs's four-volume set of Glazunov's music for solo piano, meaning that Coombs has now recorded all of Glazunov's music for piano soloist.

The two piano concertos date from relatively late in the composer's career and are lyrical works, betraying the characteristically lush orchestral textures familiar from Glazunov's symphonies and ballets.

Alexander Goedicke (Medtner's cousin!) wrote his Concertstück earlier than Glazunov's two concertos despite being the younger man. The work was published in 1900 and won the composer the Rubinstein Prize for Composition, bringing him early fame hardly matched by any subsequent successes. The Concertstück is rhapsodic, with much brilliant piano writing and a distinctly Russian flavour to its themes. Hyperion

Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936)

Piano Concerto No 1 in F minor Op 92 [31'18]

Piano Concerto No 2 in B major Op 100 [20'21]

Alexander Goedicke (1877-1957)

Concertstück in D major Op 11 [13'50]

Credits :

Conductor – Martyn Brabbins

Leader [Orchestra] – Geoffrey Trabichoff

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Stephen Coombs

HAHN : Piano Concerto In E Major ♦ MASSENET : Piano Concerto In E Flat Major (Stephen Coombs · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Jean-Yves Ossonce) (1997) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 15 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Although both concertos owe a debt to the lean and athletic piano style exemplified by Saint-Saëns, they are very different in character. The Massenet is an extrovert work culminating in a very Lisztian 'Hungarian' finale, while the Hahn is primarily lyrical and gentle, the composer's gifts as a composer of songs easily transferring to the concerto medium. Hyperion

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Piano Concerto in E flat major [31'04]

Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947)

Piano Concerto in E major [28'24]

Credits :

Conductor – Jean-Yves Ossonce

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Stephen Coombs

14.1.22

PIERNÉ : The Complete Works For Piano And Orchestra (Stephen Coombs · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Ronald Corp) (2003) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 34 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

In his time Pierné was hugely successful as composer, conductor and organist—a sort of latter-day Saint-Saëns, and indeed his music is very reminiscent of that composer. The earliest three works on this CD were all written between 1885 and 1890 and could easily be mistaken for the older composer, the piano concerto even follows the unusual layout of Saint-Saëns' 2nd piano concerto in having a scherzo but no slow movement. The Poëme symphonique of 1903 is harmonically more daring and reminiscent of Franck. This work is a true orchestral symphonic poem with the piano fully integrated into the musical argument, it is also perhaps the most impressive work on this disc and its obscurity is inexplicable.

A disc full of surprises, all of them pleasant! Hyperion

Gabriel Pierné (1863-1937)

Piano Concerto In C Minor Op 12 (19:41)

Poëme Symphonique In D Minor Op 37 13:02

Fantaisie-Ballet In B Flat Major Op 6 11:21

Scherzo-Caprice In D Major 8:08

Credits :

Conductor – Ronald Corp

Leader [Orchestra] – Bernard Docherty

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano, Liner Notes – Stephen Coombs

29.12.20

4.5.20

+ last month

BUMBLE BEE SLIM — Complete Recorded Works In Chronological Order Volume 1 · 1931-1934 | DOCD-5261 (1994) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

The first of nine releases devoted to Slim's music. As with many Document releases, the sound is pretty uneven. But considering that ...

.jpg)