Franck’s Piano Quintet and Debussy’s String Quartet make an apt and unusual coupling, each work its composer’s only, unsurpassable, contribution to the genre. Both receive authoritative performances from Marc-André Hamelin and the Takács Quartet. hyperion

Franck’s Piano Quintet and Debussy’s String Quartet make an apt and unusual coupling, each work its composer’s only, unsurpassable, contribution to the genre. Both receive authoritative performances from Marc-André Hamelin and the Takács Quartet. hyperion

CÉSAR FRANCK (1822-1890)

1-3. Piano Quintet In F Minor M7 (1879) (37:14)

Ensemble – Takács Quartet

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918)

4-7. String Quartet In G Minor L91, Op 10 (1893) (25:09)

Ensemble – Takács Quartet

Credits :

Takács Quartet :

Cello – András Fejér

Viola – Geraldine Walther

Violin [Violin I ] – Edward Dusinberre

Violin [Violin II] – Károly Schranz

Cover artwork: Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

19.1.26

FRANCK : Piano Quintet · DEBUSSY : String Quartet (Marc-André Hamelin · Takács Quartet) (2016) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

3.4.25

ALKAN : Grande Sonate 'Les quatre âges' · Sonatine · Le Festin d'Ésope (Marc-André Hamelin) (1995) APE (image+.cue), lossless

The Grande Sonate and Sonatine, brought together on this recording, are Charles-Valentin Alkan’s first and last masterpieces for solo piano and illustrate two extremes in the composer’s aesthetic development.

The Grande Sonate and Sonatine, brought together on this recording, are Charles-Valentin Alkan’s first and last masterpieces for solo piano and illustrate two extremes in the composer’s aesthetic development.

In many respects, the Grande Sonate, Op 33, is one of the pinnacles not only of Alkan’s output but of the entire Romantic piano repertoire. In writing a piano sonata, Alkan was reviving and preserving a form which was not merely undervalued by the French but was even described by Schumann as being ‘worn out’. In the hands of this extremely discreet composer, it could almost claim to be a manifesto: composed in the wake of the 1848 Revolution, and dedicated to his father, it is prefaced by what constitutes one of the rare official examples of the composer’s taking an aesthetic stand on an extremely controversial matter: programme music. His text is not to be overlooked:

Much has been said and written about the limitations of expression through music. Without adopting this rule or that, without trying to resolve any of the vast questions raised by this or that system, I will simply say why I have given these four pieces such titles and why I have sometimes used terms which are simply never used by others.

It is not a question, here, of imitative music; even less so of music seeking its own justification, seeking to explain its particular effect or its validity, in a realm beyond the music itself. The first piece is a scherzo, the second an allegro, the third and fourth an andante and a largo; but each one corresponds, to my mind, to a given moment in time, to a specific frame of mind, a particular state of the imagination. Why should I not portray it? We will always have music in some form and it can but enhance our ability to express ourselves; the performer, without relinquishing anything of his individual sentiment, is inspired by the composer’s own ideas: a name and an object which in the realm of the intellect form a perfect combination, seem, when taken in a material sense, to clash with one another. So, however ambitious this information may seem at first glance, I believe that I might be better understood and better interpreted by including it here than I would be without it.

Let me also call upon Beethoven in his authority. We know that, towards the end of his career, this great man was working on a systematic catalogue of his major works. In it, he aimed to record the plan, memory or inspiration which gave rise to each one.

The composition and publication of the Grande Sonate occurred at a crucial moment in the composer’s life. During the summer of 1848, when the Revolution was not yet over, Zimmerman, Alkan’s teacher, resigned from his position as Professor of Piano at the Paris Conservatoire. It would seem natural enough that Charles-Valentin, his most brilliant and promising student, should succeed him; but in the troubled climate of the time, and as a result of some predictable intrigue, it was in fact a second-rate musician, Antoine Marmontel, who was to gain the post. This was a particularly bitter pill for Alkan to swallow; he was to fade gradually further into obscurity and renounce all public and official posts. The Revolution was also to harm any publicity which might have surrounded the publication of the Grande Sonate: although it was well heralded in the music magazines, it would appear that there was not one single review of the piece, nor one public performance thereafter. The British pianist Ronald Smith is fully justified in thinking that he brought the piece to life when he gave it its first public performance in America in 1973!

Alkan was to try his hand at the piano sonata form on four occasions: the Grande Sonate, Op 33, the Symphony and Concerto for solo piano, Op 39, and the Sonatine, Op 61, all illustrate the discrepancies between an inherited Classical form and the trends of Romanticism. The astonishing complexity of the Grande Sonate was certainly disconcerting for his contemporaries and sufficiently justified his decision to give the programme a preface. Let us not forget three of its most markedly original features: as in the Symphony and Concerto, Op 39, and well before Mahler or Nielsen, the tonality evolves during the course of the work without returning to a ‘root tonality’; confining ourselves to the start of each movement, the keys are respectively D major, D sharp minor, G major, G sharp minor; if we focus purely on the endings, we find B major, F sharp major, G major and G sharp minor. The sequence of tempi was equally likely to be disconcerting for the listener: in place of the usual quick–slow–quick, Alkan puts four successively slower movements one after another. Finally, he invokes two of the great Romantic myths – Faust and Prometheus; the first, immortalized by Goethe, enjoyed a popularity kept alive by Berlioz, Gounod, Liszt and Schumann etc, while Prometheus takes us back to antiquity, to an era which Alkan, being passionate about the Classics, knew well and which he often referred to in his compositions.

The sonata opens with ‘20 ans’, a frenzied scherzo which frequently reminds one of Chopin’s Scherzo No 3. Straightaway, the 3/4 time is juxtaposed with accents on every other beat. The trio portrays the awakening of love, working its way gradually through various sections, from ‘timidly’ to ‘lovingly’ and on to ‘with joy’. The coda brings the movement to a whirling conclusion.

‘30 ans, Quasi-Faust’ is the heart of the sonata. It opens with the Faust theme which, in four bars, covers the whole keyboard and states the rhythmic formulae which will permeate the entire movement. There follows the Devil’s theme, in B major, which is the inversion of Faust’s theme. Marguerite’s theme, in G sharp minor and then major, presented at first in a mood of sweet sadness, passes through numerous climatic changes. The development and the return of the exposition lead on to four huge arpeggios which spread across every octave of the keyboard. Now comes a fugue, a horribly complicated eight-part fugue, which the eye alone can follow in the score; in order to make it legible, the composer himself establishes the use of different manuscript styles! The fugue continues until the entrance of ‘Le Seigneur’, and the movement concludes with a clear victory of Good over Evil, thus inspired by Goethe’s Faust Part 2, unlike the ending of Berlioz’s opera-oratorio where the composer boldly damns his hero.

‘40 ans, un ménage heureux’ presents a picture of unspoken Romance, interrupted on two occasions by a charming three-voice digression entitled ‘les enfants’; this latter section exhibits a use of thirds, sixths, fifths which is very untypical of Alkan who, unlike Chopin, usually shows little interest in anything other than octaves and chords. With the return of the opening section, the theme, treated in canon, becomes even more animated. The clock striking ten is the signal for prayer.

‘50 ans, Prométhée enchaîné’ draws us to the abyss. As an epigraph, Alkan cites several verses of the Aesychlus tragedy:

No, you could never bear my suffering! If only destiny would let me die! To die … would release me from my torments! Would that Jupiter had not lost his power. I will live whatever he might do … See if I deserve to suffer such torments! [lines 750–754, 1051, 1091 (the end of the play)]

After the victory in ‘Quasi-Faust’ and the joy of the happy household – something which the composer would always be denied – ‘50 ans’ ends with an acknowledgement of failure, in a visionary piece written without hint of pomposity or excess. Thinking about the composer’s destiny, the piece is also a premonition.

The Sonatine, Op 61, was written fourteen years after the Grande Sonate and forms a striking contrast to it. Concise and concentrated in the extreme, refined in its style of writing, and of exceptional technical difficulty, it is a gem of equilibrium and perhaps presents Alkan at his most accessible. Its first movement, although swept along and interrupted by violent angry outbursts, maintains a profound coherence, reinforced by the taut conjoining of its two themes. The Allegramente which follows, in F major, belongs within the best tradition of Alkan’s falsely naive works. It is immediately reminiscent of the slow movement from Maurice Ravel’s Sonatine; Ravel was, moreover, familiar with the music of this, the composer of Le festin d’Esope. The Scherzo-Minuet, in D minor, is one of those perpetual motion pieces of which the composer was so fond; he interrupts its driving rhythm with a trio which eases the pace of the movement but is unsettled by various rhythmic and harmonic devices. The finale, Tempo giusto, opens with startling fifths which conjure up the empty chords of a cello or the toll of bells, in the style of Mussorgsky in his Pictures at an Exhibition; the sections which follow vary greatly without ever altering the movement’s deep cohesion. A dry fortissimo chord brings the four movements to a close.

Le festin d’Esope completes the cycle of 12 Études dans tous les tons mineurs, Op 39, to which the Symphony and the huge Concerto for solo piano belong. The term ‘study’ should be taken to mean the same as it does to Chopin and a fortiori Clementi or Cramer. Alkan, more so even than Liszt, expands the scope of this form to the dimension of a symphonic poem, a rhapsody. Le festin d’Esope consists of a series of variations on a theme which one might liken to traditional Jewish melodies. The argument is to be found again in Jean de la Fontaine’s La vie d’Esope le Phrygien:

One market day, Xantus, who had decided to treat some of his friends, ordered him to buy the best and nothing but the best. The Phrygian said to himself, ‘I’m going to teach you to specify what you want, without leaving it all to the discretion of a slave’. And so he bought nothing but tongue, which he adapted to each different sauce; the starter, the main course, the dessert, everything was tongue. At first the guests praised his choice of dish; but by the end they were filled with disgust. ‘Did I not order you’, said Xantus, ‘to buy the best?’ ‘And what could be better than tongue?’ answered Aesop. ‘It is our connection to civil life, the key to the sciences, the organ of truth and reason. Through it, we build and police our towns; we learn; we persuade; we rule over assemblies; we fulfil the greatest of all our duties, namely to praise God.’

The theme of the tongue, the most important organ and function, is frequently mentioned in the Bible, Alkan’s favourite book. The variations, apart from dealing with various technical problems, illustrate without doubt every possible transformation that a theme could go through; in addition, one is presented with a succession of little tableaux of the animal kingdom, Alkan giving us several hints of this such as the marking abajante.

The Barcarolle which completes this recital is taken from the third of Alkan’s five Recueils de Chants for piano. These five books are distinctive in that they are modelled on Mendelssohn’s first collection of Lieder ohne Worte; they follow the same tone sequence and conclude with a barcarolle. The Barcarolle from the third collection is undoubtedly one of Alkan’s most seductive and meaningful pieces: its melody imprints itself immediately on one’s memory, and the whole work radiates a melancholic sweetness. (François Luguenot - Hyperion)

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

1-4. Grande Sonate "Les Quatre Âges" Op 33 (38:25)

5-8. Sonatine Op 61 (17:56)

9. Barcarolle Op 65 No 6 3:53

10. Le Festin D'Esope Op 39 No 12 8:45

Credits :

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

Painting [Cover Painting] – Tiziano Vecellio

2.4.25

ALKAN : Concerto for solo piano · Troisième recueil de chants (Marc-André Hamelin) (2007) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Anyone familiar with the unfailing digits and seemingly inexhaustible energy of Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin would find the very prospect of his recording Charles-Valentin Alkan's giga-difficult Concerto for solo piano as a natural match of pianist and piece. This 50-minute mega-monstrosity -- the first movement alone lasts nearly a half an hour, and runs to more than 70 pages -- has been played only by pianists intrepid and skilled enough to make the voyage, the short list including Egon Petri, Alkan acolyte Ronald Smith, and John Ogdon, in one of his finest recorded outings. With Hamelin, this Hyperion release Alkan: Concerto for Solo Piano is all the more amazing as this is his second recorded traversal of the work, having done an earlier version for the Music & Arts label in 1993. What the 13-year interim has yielded is a deepening of Hamelin's interpretation, to the point where the rapid fire runs, leaping octaves, and thundering crescendos that characterize the work have become second nature and Hamelin is able to mainly concentrate on making Alkan's concerto sound like the glorious vision that it is. And that's not to mean the earlier recording was necessarily "bad," it's just that in the meantime he has achieved total independence from the technical challenge that Alkan's concerto represents.

This work is such a trip; it is a combination of symphony and concerto where all of the orchestral and solo parts are wound into just the two hands of the pianist. Apart from the first movement, it has a searing Adagio at its center and the Allegretto finale is marked alla barabaresca. As Brobdingnagian as the concerto is, however, Alkan never digresses; it is taut and completely strict in a formal sense even as it is likely the most expansive work for piano solo that the nineteenth century has to offer. Hamelin has mastered it, a feat so awesome that it almost makes one forget that the Hyperion disc also offers a late and lovely Alkan work as filler, the Third Book of the Recueil de Chants (1863), never before recorded in its entirety; Raymond Lewenthal recorded the Barcarolle alone on his groundbreaking RCA Victor LP Piano Music of Alkan in 1965. In a sense, Hyperion's Alkan: Concerto for solo piano illustrates how far we've come with Alkan in nearly five decades' time; from the enterprising, exploratory readings of Lewenthal in the 1960s to total command of Alkan's "impossible" pianist language in the 2000s. The one thing Alkan lacks is a place in the standard literature, and it doesn't appear as though he's ever going to have that, though if anyone can operate at the exalted level of advocacy that such a transition of thinking about Alkan would require, then Marc-André Hamelin is probably the man. Uncle Dave Lewis

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

1-3. Concerto For Solo Piano Op 39 Nos 8-10 (49:35)

4-9. Troisième Recueil De Chants Op 65 (17:57)

Credits :

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

Front illustration : The Kiss of the Vampire (1916) by Boleslas Biegas (1877-1954)

CHARLES-VALENTIN ALKAN : Concerto for solo piano (Marc-André Hamelin) (1992) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

31.3.25

ALKAN : Symphony for solo piano • Trois Morceaux dans le genre pathétique (Marc-André Hamelin) (2001) APE (image+.cue), lossless

Marc-André Hamelin's first solo Alkan recording (CDA66794) met with the most superlative critical reception imaginable (culminating in Fanfare magazine's "one of the best releases of anything to have been made, a classic of the recorded era"). This follow-up proves to be no less spectacular.

The disc is framed by two of the 'monster' works for which Alkan is notorious. The four movements of the Symphony for solo piano are taken from his magnum opus, the 12 Studies in the minor keys Op 39. This piece has become one of Alkan's best known but never has its finale (once described as a 'ride in hell') been so spectacularly thrown off. The Trois Morceaux dans le genre pathétique are the earliest pieces in which Alkan's true personal style became apparent. These are three massive studies each with programmatic titles and an atmosphere of Gothic horror that requires a supreme virtuoso to tackle their outlandish technical demands. This is their first recording.

The recital is completed by three pieces of rather religious inspiration. While their scale and technical demands are those of a more conventional composer, their quirky sound-world and often sardonic mood confirm the composer as our reclusive Frenchman. Hyperion

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

1-4. Symphony For Solo Piano Op 39 Nos 4-7 (26:06)

5. Salut, Cendre Du Pauvre! Op 45 (8:40)

6. Alleluia Op 25 (2:40)

7. Super Flumina Babylonis Op 52 (Paraphrase Du Psaume 137) (6:30)

8-10. Souvenirs: Trois Morceaux Dans Le Genre Pathétique Op 15 (29:56)

Credits:

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

Illustration [Front Illustration: 'The Ballad Of Lenore, Or 'The Dead Go Fast'' (1839) – Horace Vernet

28.3.25

LEO ORNSTEIN : Suicide In An Airplane · Danse Sauvage · Sonata 8 And Other Piano Music (Marc-André Hamelin) (2002) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

When Leo Ornstein died in February 2002, the musical world lost a fascinating composer, quite possibly the oldest of all time (the year of his birth is uncertain, but he was probably 109 years old). Ornstein had an extraordinary life: he was a child-prodigy pianist in his native Russia, a refugee from anti-Semitism, an avant garde American composer and a virtuoso pianist of international renown in his early twenties. However, at the height of his fame he voluntarily turned his back on the limelight and took sanctuary in increasing obscurity, and having been almost entirely forgotten, he lived long enough to take satisfaction in the re-emergence of an interest in his music—of which this CD is early testimony.

When Leo Ornstein died in February 2002, the musical world lost a fascinating composer, quite possibly the oldest of all time (the year of his birth is uncertain, but he was probably 109 years old). Ornstein had an extraordinary life: he was a child-prodigy pianist in his native Russia, a refugee from anti-Semitism, an avant garde American composer and a virtuoso pianist of international renown in his early twenties. However, at the height of his fame he voluntarily turned his back on the limelight and took sanctuary in increasing obscurity, and having been almost entirely forgotten, he lived long enough to take satisfaction in the re-emergence of an interest in his music—of which this CD is early testimony.

Ornstein's early piano works were unlike anything else in music. He employed the piano as a percussion instrument, pounding out savage rhythms and ferocious cluster-chords with a raw primal energy. He embraced atonality independently of Schoenberg and rhythmic primitivism unaware of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring. The titles of his pieces—among them Danse sauvage and Suicide in an Airplane—reflected the extremist brutality of the music and rapidly gained him notoriety. By his early twenties he was one of the most highly reputed of contemporary composers.

The music on this CD comes from each end of Ornstein's improbably long creative career. The shorter works were written at its outset, while the large-scale, kaleidoscopic Eighth Piano Sonata, his last composition, was finished in September 1990, when he was in his late nineties.

The ever-inquisitive Marc-André Hamelin gives commanding performances of these supremely demanding works. The result is a stunning disc that reveals one of the twentieth century's most original and quirkily imaginative creative minds. Hyperion

Leo Ornstein (1892-2002)

1. Suicide In An Airplane (3:46)

2. À La Chinoise (4:59)

3. Danse Sauvage (2:48)

4-13. Poems Of 1917 (17:03)

14-22. Arabesques, Op. 42 (10:22)

23. Impressions De La Tamise (7:57)

24-29. Piano Sonata No. 8 (30:12)

Credits :

Painting – Monika Giller-Lenz

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

4.9.24

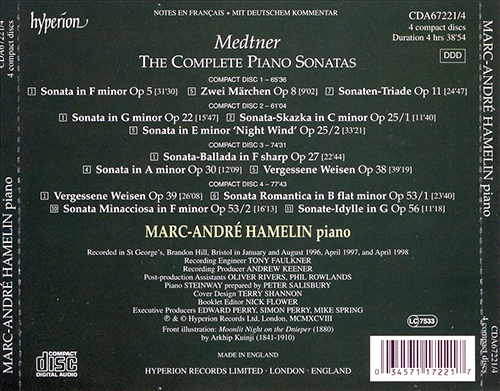

MEDTNER : The Complete Piano Sonatas · Forgotten Melodies I - II (Marc-André Hamelin) 4xCD (1998) APE (tracks), lossless

'I repeat what I said to you back in Russia: you are, in my opinion, the greatest composer of our time.' – Sergei Rachmaninov (1921)

'I repeat what I said to you back in Russia: you are, in my opinion, the greatest composer of our time.' – Sergei Rachmaninov (1921)

It would be hard to overestimate the importance of this set.

Medtner's piano compositions are arguably the last area of great Romantic piano repertoire to be discovered. His music is difficult, both technically and intellectually, and does not 'play to the gallery', which may explain its neglect. But once his world has been entered it proves endlessly fascinating and compelling, his work growing in stature with every hearing until one is left in no doubt as to its overwhelming effect.

Central to his output are the 14 Piano Sonatas (though the title covers a multitude of structures and sizes) and here for the first time we have the complete cycle recorded by one artist. Hyperion Tracklist & Credits :

BUSONI : Late Piano Music (Marc-André Hamelin) 3CD (2013) FLAC (image+.cue) lossless

The late piano works of Ferruccio Busoni can be characterized as virtuoso music par excellence, and because of their contrapuntal complexity, harmonic density, and technical difficulty, these pieces can have no greater champion than Marc-André Hamelin, the virtuoso's virtuoso. This Hyperion set of three CDs presents music that is far from well-known, and its obscurity adds another layer of unnecessary mystery. However, Hamelin is just the artist to sweep that all aside and present these seldom played pieces with clarity, precision, and élan to make them truly impressive. Busoni's music transcends any fixed style and is more than pastiche, though much of his work shows the influence of J.S. Bach, whose music Busoni frequently adapted for the modern piano and found to be a constant source of inspiration. Additionally, Busoni was a leader in the development of pantonal music, which is often confused with atonality, and worked out various ideas he described in his book, The Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music. Hamelin is perhaps the best guide to the complicated world of Busoni, and thanks to his astonishing playing, this music communicates more directly and powerfully than many other attempts by other pianists. Hyperion's recording is clear and reasonably close to the piano, so virtually every note can be heard. Blair Sanderson

The late piano works of Ferruccio Busoni can be characterized as virtuoso music par excellence, and because of their contrapuntal complexity, harmonic density, and technical difficulty, these pieces can have no greater champion than Marc-André Hamelin, the virtuoso's virtuoso. This Hyperion set of three CDs presents music that is far from well-known, and its obscurity adds another layer of unnecessary mystery. However, Hamelin is just the artist to sweep that all aside and present these seldom played pieces with clarity, precision, and élan to make them truly impressive. Busoni's music transcends any fixed style and is more than pastiche, though much of his work shows the influence of J.S. Bach, whose music Busoni frequently adapted for the modern piano and found to be a constant source of inspiration. Additionally, Busoni was a leader in the development of pantonal music, which is often confused with atonality, and worked out various ideas he described in his book, The Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music. Hamelin is perhaps the best guide to the complicated world of Busoni, and thanks to his astonishing playing, this music communicates more directly and powerfully than many other attempts by other pianists. Hyperion's recording is clear and reasonably close to the piano, so virtually every note can be heard. Blair Sanderson

Tracklist & Credits :

28.8.24

CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL Bach : Sonatas & Rondos (Marc-André Hamelin) 2CD (2022) FLAC (image+.cue) lossless

The music of C P E Bach makes complex stylistic demands of the performer like little else of its time, the extraordinary drama and intensity tempered by Enlightenment elegance and the influence of the Baroque. Marc-André Hamelin’s performances set new standards in this endlessly absorbing repertoire. hyperion-records.co.uk Tracklist & Credits :

The music of C P E Bach makes complex stylistic demands of the performer like little else of its time, the extraordinary drama and intensity tempered by Enlightenment elegance and the influence of the Baroque. Marc-André Hamelin’s performances set new standards in this endlessly absorbing repertoire. hyperion-records.co.uk Tracklist & Credits :

3.3.22

IVES : Concord Sonata; BARBER : Piano Sonata (Marc-André Hamelin) (2004) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

America’s two greatest twentieth-century piano sonatas are here given predictably stunning performances by Marc-André Hamelin. This is the pianist’s second recording of the Ives ‘Concord Sonata’, a piece he has played for over twenty years in performances that have often been regarded as definitive. As his thoughts on this landmark work matured, Marc became very keen to revisit the work in the studio in this 50th anniversary year of Ives’s death.

The Barber is an apt if unusual coupling. Premiered by Horowitz, with a blisteringly virtuosic final fugue written specially at his suggestion, this is one of only a few modern piano works to have become a genuine audience favourite. Hyperion

16.1.22

HENSELT : Piano Concerto Op16 • Variations De Concert Op11 (First Recording) ♦ ALKAN : Concerto Da Camera Op10/1 (First Recording) • Concerto Da Camera Op10/2 (Marc-André Hamelin · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Martyn Brabbins) (1994) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 7 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The coupling of works by Alkan and Henselt is not as arbitrary as might appear. Born six months apart, both enjoyed long lives and died within eighteen months of each other; both have been entirely overshadowed by their more illustrious contemporaries Liszt and Chopin (to the extent that they have been assigned to the footnotes of musical history), though both had an individual approach to the piano with a style as clearly defined and as idiosyncratic as their two peers; both were recluses, rarely playing their works in public; both were transcendent technicians, exploring the potential of their instrument in ways which were to influence other pianists and composers of piano music; both were eccentrics in their personal habits and lifestyles; both have been almost universally ignored by the majority of concert pianists; and neither of their names is known to the general music-loving public. (Although there has been a marked revival of interest in Alkan’s work over the past three decades, there is still only grudging acknowledgement of his importance from the musical ‘establishment’.)

The four works presented here were all written at around the same time – that is to say the twelve or so years between 1832 and 1844. Only one of them has ever featured in the regular repertoire of any pianist; Alkan’s Concerto No 1 probably has not been realized in this its original form since its initial performances; Henselt’s Meyerbeer variations have certainly not been performed by anyone this century (its publishers Breitkopf and Härtel confirmed this when checking their archives); Alkan’s Concerto No 2 has been recorded before, notably by Michael Ponti, who was also responsible for one of only two previous recordings of the Henselt concerto.

Of the myriad contributions to the genre written during the first part of the nineteenth century, Henselt’s Piano Concerto in F minor, Op 16, is the one whose neglect is the hardest to explain. It has the composer’s individual stamp on every bar, it is original in its writing (if not its structure), its orchestration is more than adequate and at times masterly, its themes are varied and memorable, the musical and technical challenges for the soloist are equalled only by their effect on the listener, and the whole work has the feel of white-hot inspiration. Henselt never reached the same height again. Is it a good piece of music? Yes. The piece may not offer revolutionary concepts (indeed, much of it is firmly rooted in the past), but that does not alter its intrinsic merit. It should be part of the core repertoire.

Where did it come from? What was the genesis of this most demanding of Romantic concertos? Its composer was born on 9 May 1814 at Schwabach, a small town in Bavaria, close to Nuremberg. His father Philipp Eduard Henselt is described variously as a cotton manufacturer or cotton weaver, whose marriage to Caroline Geigenmüller produced six children. When Adolf was three the family moved to Munich. It was not a musical family but he had his first piano lessons at the age of five, gave his first public recital when he was fifteen and, in 1831, under the auspices of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, was granted a stipend to study piano in Weimar with Hummel and composition in Vienna with the master theorist and pedagogue Simon Sechter.

The early part of his career progressed conventionally enough, though his elopement with (and eventual marriage to) the wife of one of Goethe’s friends must have raised a few eyebrows at the time. Aristocratic in looks and bearing, he would in later years resemble the Emperor Franz Josef. His early success touring Germany and Russia was underlined by the reception of his sets of studies (Opp 2 & 5) published in 1837 and 1838. The Douze études caractéristiques de concert (Op 2) were dedicated to his royal patron and include the best (only?) known work of Henselt today – ‘Si oiseau j’étais, à toi je volerais’ (‘Were I a bird, I’d fly to you’), a tricky feather-light study in sixths once given the distinction of a recording by Rachmaninov. These were followed by the Douze études de salon (dedicated to HRH Marie the Queen of Saxony) which, with the previous set of twelve, alternate through all the major and minor keys.

These studies attracted a lot of attention for the young virtuoso, many of them presenting technical problems different from those in Chopin’s two sets (published a few years previously) but still maintaining the new concept of exercises wrapped in poetry. They were Henselt’s ‘calling card’ and to the present day remain beyond the capabilities of many pianists. Even the legendary Anton Rubinstein had to admit defeat; after working on the études and F minor Concerto for a few days, he realized ‘it was a waste of time, for they were based on an abnormal formation of the hand. In this respect, Henselt, like Paganini, was a freak.’ Many passages in the études presage the harmonic progressions and technical difficulties of the F minor Concerto. There is a liberal use of chords of the tenth (sometimes twelfth) and arpeggios with a larger stretch than an octave. It wasn’t that Henselt had large hands – au contraire, he is known to have had small hands with short fleshy fingers. But by means of diligent, self-consuming practice he managed to achieve an amazing degree of elasticity with an extension that could reach C–E–G–C–F in his left hand and B–E–A–C–E in the right (try it!).

All this augured well for an important career as a pianist and composer. Neither came about. Towards the end of his life Henselt himself recognized (in a letter to the critic La Mara) that he had not fulfilled his early promise:

I am persuaded that because I performed so little of what I promised in my youth, it would be impossible to speak about me without censure … you think perhaps that I undervalue myself; by no means, but I live in no illusion about myself. I know, for instance, quite well, that some of my compositions are among the best which have been written for the instrument – that I have written better studies than many a so-called composer. Still, this is far too little: that is to say, the works that deserve mention are far too few in number; I have but given a proof that I might have been a composer: the circumstances of my life were, however, not favourable to it. Above all, the passion for virtuosity should have never taken possession of me.

As a composer, he simply had nothing else to say after the age of thirty, recognized the fact and lived with it. From the completion of the F minor Concerto (1844) to his death, there is no advance in style or content in the few remaining works. This lends (albeit by default) a pleasing one-ness to his entire output, a ‘Henseltian’ style as recognizable as Chopin’s, or Liszt’s or, more pertinently, Alkan’s.

Given the paucity of his creativity, the extent of his influence on piano playing is remarkable for two reasons. First by way of the prodigious technical invention of the études (and, for that matter, the Concerto). As Richard Davis put it: ‘The effect of [Henselt’s] extensions – [his] original, if at times impractical contribution to piano technique – resulted in fuller tone in the bass and greatly increased coverage in the upper registers of the keyboard with economy of notes and minimal movement of the hand and arm, and is to be seen in much of the later music of Balakirev, as well as that of Lyapunov, Scriabin and Rachmaninov (who must have greatly benefited from his study of Henselt), and we may believe that the great reserves of resources engendered as a result of this extra ability really did give control to all these composers as pianists.’

The second influence Henselt had on piano playing was a result of his position in the cultural life of Russia. His triumph as a visiting concert pianist in St Petersburg in 1838 led immediately to him being named Court Pianist. From then until his death Henselt spent all but the summer months each year in the Russian city where he enjoyed a princely lifestyle and was on intimate terms with three successive tsars. His arrival coincided with the upsurge of interest in a Nationalist school of music. In 1863 he was made Inspector General of all the royally-endowed musical institutions in Russia. As Bettina Walker engagingly observes in My Musical Experiences (1880):

When one takes into account that in St Petersburg alone there are five such Imperial endowments, three in Moscow, and one or more in most of the larger cities throughout this vast empire, and that, furthermore, some of these institutes count their students by the hundred (that, for instance, of Nicholas in St Petersburg, numbers six hundred pupils), we shall then be in a position to realize what an enormous influence over pianoforte playing throughout all Russia was thus placed in Henselt’s hands. It is not, indeed, too much to say that never before has a single musician had so wide a sphere of musical activity opened to him; and though that influence extended over one single department in music’s vast domain – that of pianoforte playing – still, if we consider that it was these institutes which trained all the governesses and female teachers throughout Russia, that all the musical instruction was (and still is as I write) given by teachers who had either been actually pupils of Henselt, or else been thoroughly drilled by his lady-professors, it is not too much to assume that for more than a quarter of a century his influence has been felt in more or less every home in Russia where there was a pianoforte.

And this does not take into account the influence of Henselt’s own private pupils. Among them were Rachmaninov’s grandfather and Nicolai Zverev. Zverev taught Rachmaninov himself, Lhevinne, Siloti and Scriabin. Here we have the foundations of the present Russian school of piano-playing with its emphasis on singing melody and freedom of hand movement. Henselt’s contribution to the piano was at least as significant as that of Liszt and Leschetizky.

What was he like as a pianist? All writers who left detailed accounts of Henselt (and there were many) agree on one thing: his cantabile playing was unequalled. (Even Liszt was envious: ‘I could have had velvet paws like that if I had wanted to’, he told his pupils.) They also agree that no one in the history of piano playing was such a compulsive practiser, with the exception, perhaps, of Leopold Godowsky (whose own music must have been influenced by Henselt’s writing; certainly both share a common fault of frequent over-elaboration at the expense of the musical content). During a recital, even between items, Henselt would leap to his muffled practise piano in the wings and keep his fingers working, almost like a child’s comforter. Von Lenz described him at home practising on a piano muffled by feather quills, playing Bach fugues while simultaneously reading the Bible: ‘After he has played Bach and the Bible quite through, he begins over again.’

Of all the great pianists (and there’s no doubt that he was one of the great players of the last century) he suffered more than any from stage fright. The thought of playing in public made him physically ill and in the last thirty-three years of his life it’s reckoned that he gave no more than three public recitals. Yet many report that when in the company of friends or, even better, when alone, he was unsurpassed, some say not even by Liszt. The oft-quoted story of the pianist Alexander Dreyschock overhearing Henselt playing is worth repeating. The American pianist William Mason recalls Dreyschock telling how, calling on Henselt in St Petersburg one morning and going up the staircase to his room, ‘he heard the most lovely tones of the piano-forte imaginable. He was so fascinated that he sat down at the top of the landing and listened for a long time. Henselt was repeating the same composition and his playing was specially characterized by a warm, emotional touch and a delicious legato, causing the tones to melt, as it were, one into the other, and this, too, without any confusion or lack of clearness.’ Eventually Dreyschock interrupted and announced himself, asking what it was that Henselt had been playing. It was one of his own pieces he was composing and Dreyschock begged him to play it to him again: ‘Alas! His performance was stiff, inaccurate, even clumsy, and all of the exquisite poetry and unconsciousness of his style completely disappeared. It was quite impossible to describe the difference; and this was simply the result of diffidence and nervousness which, as it appeared, were entirely out of the player’s power to control.’

Henselt played his F minor Concerto in public only rarely. Who could blame him, with a temperament that left him below his best under pressure (a further similarity with Godowsky)? Liszt, it is said, sight-read the whole work from the manuscript. Other pianists who included it in their repertoire were Liszt’s pupils Hans von Bülow, Arthur Friedheim and Emil Sauer, the latter playing it at his New York debut in 1899. Busoni played it, and so did his pupil Egon Petri (who said it was one of the hardest pieces he had ever played). Louis Moreau Gottschalk is said to have performed it, and also Vladimir de Pachmann, who knew Henselt and edited his works. So it comes as something of a surprise after this list of barnstormers to learn that it was Clara Schumann who gave its first performance. This was in 1844 (though the work was not published until two years later).

The first two bars of the F minor Concerto contain not only the three ascending notes which provide a motif for each of the three first-movement subjects but, in its three descending bass notes, a figure which when transposed to the key of C sharp minor reveals one of music’s most famous openings. Raymond Lewenthal (who provided the first recording of the work) was not the first to wonder whether it is a coincidence or a conscious salute to Henselt that Rachmaninov’s Op 2 No 3 Prelude commences with that same doom-laden phrase. There is no doubt that Rachmaninov knew Henselt’s work intimately and played the concerto when a young man.

The formidable piano entry gives notice of the scale of the writing to come. The soloist is given few breathers throughout, though in the midst of the hectic first movement come sixteen bars of muted strings in a Religioso variation on the three-note subject (a marvellous touch this) before the soloist launches into a barrage of ferocious arpeggios embroidering the Religioso theme. The movement continues with constant words of encouragement from Henselt (‘agitato’, ‘crescendo assai’, ‘sempre fortissimo’) before a tutti concludes the movement in a triumphant blaze of F major. If the relentless, constant rhythmic pulse of this Allegro patetico is rooted in the late Classicism of Weber and Mendelssohn, the second movement (Larghetto) looks to the future with echoes of Chopin. A similar three-note motif hints at the Rachmaninov Prelude again and it features piano scoring on four staves (a device, incidentally, used very little by any other composer until the C sharp minor Prelude, make of it what you will). This is firmly in the Romantic mould, ‘tempo rubato’ et al, and, for its melodious charm, its variety of emotion and altogether original conception, ranks among the most felicitous slow movements of the genre.

How does Henselt top this? With an Allegro agitato in 6/8, commencing with an onslaught of octaves prefacing a catchy and deceptively simple rondo. The left-hand triplets alone would knock the stuffing out of the average conservatory professor and the writing throughout is extraordinarily energetic, requiring enormous stamina and athleticism. No wonder Henselt was a fitness freak – one of music’s earliest recorded joggers who exercised regularly with the royal family.

The finale has been likened by Raymond Lewenthal to ‘a prophecy of the doom of the Tzarist regime as it frantically, furiously, frivolously dances its way to perdition’. Not such a fanciful picture, for there is a strong Russian flavour to this movement; its second subject could be a waltz by someone like Arensky, and can we not hear Tchaikovsky somewhere just round the corner? Although its spine may be in the well-worked European tradition, its character is distinctly un-French and -German. This last movement also reveals one important reason behind the concerto’s disappearance from the repertoire. The demands of the solo part are immense – though not by any means unpianistic, unplayable, inelegant or unconquerable – but they are the kind of difficulties that an audience cannot readily appreciate without a score (another trait shared with Godowsky’s music). The soloist has to work very hard indeed for effects that are not always apparent.

It’s good to welcome the concerto back to the catalogue in this distinguished performance by a soloist who is an authentic advocate of this music.

The Variations de concert, Op 11, on ‘Quand je quittai la Normandie’ from Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable are dedicated to ‘Her Majesty L’Impératrice de toutes les Russies’. Henselt produced this diverting confection in 1840 after his move to Russia, simultaneously shifting the subject of his dedications from a Bavarian to a Russian monarch. He was not the first to use Meyerbeer’s popular success for the basis of variations: Chopin’s Grand Duo in E for cello and piano was written in 1832, a year after the opera’s Paris premiere; Liszt in his Reminiscences, and Sigismund Thalberg in his Fantasy, used themes from the opera too. Henselt’s are out of the school of Chopin’s ‘Là ci darem la mano’ variations of some thirteen years earlier. Though there is less evidence of his études than in the concerto, it’s a work which partly justifies Schumann’s assessment of Henselt as ‘the Northern Chopin’. That said, it could never have been written by Chopin (nor indeed Mendelssohn; quite apart from stylistic comparisons it falls some way below their inspirational best). Its brilliant and demanding writing are more Lisztian than anything. After an opening deluge of octaves, note-spinning and a Larghetto introduction, Meyerbeer’s perky theme is followed by seven variations (with a fearsome cadenza before the last), each linked by an orchestral breathing space.

If Henselt had nothing more to say after the age of thirty, the same could not be said of Charles-Valentin Morhange (the name with which Alkan was first registered: Alkan was his father’s first name and he adopted this as his surname early on). The ideas came pouring forth in bewildering variety, his earliest in the Kalkbrenner-Mendelssohn-Weber mould but taking flight during his life into strange, prophetic visions.

Alkan is one of the most puzzling cases of ‘composer neglect’. He wrote at a level consistent with the greatest contemporary writers for the piano – Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, Brahms –, introduced new forms, and produced music every bit as inventive as that of his peers, and yet he was all but forgotten until three decades ago. Since then the advocacy of Ronald Smith and Raymond Lewenthal (names to which can now be added Laurent Martin, Bernard Ringeissen and Marc-André Hamelin) has persuaded many people that Alkan, like Chopin and Liszt, was a genius.

One can see why he dropped out of sight: his music was advanced for its day. Like Henselt, he did little to promote it in the way that Liszt, Wagner, Berlioz and the other moderns did. The piano-writing is for the most part ferociously hard to play; he had few contemporaries to champion it. Musical tastes change; the world had tasted Debussy, Bartók and Schoenberg before anyone bothered to investigate this nineteenth-century dinosaur. Since Alkan’s death, the likes of d’Albert, Bauer, Ganz, Busoni and Arrau have included odd bits of his music in their repertoire at some point, but it was not until the arrival on the scene of Egon Petri in the first decades of this century that his major works (in particular the Symphony and Concerto for solo piano) were heard at all.

And what a strange, bitter man he was, a misanthrope who had two homes in Paris (one of them in the Square d’Orléans where he was a neighbour of Chopin and George Sand) so that he could avoid visitors, a great pianist (Liszt declared that Alkan had the greatest technique he had ever known) but who, like Henselt, seldom played in public. He had an illegitimate son with the wondrous name of Elie Miriam Delaborde who shared his dwelling with two apes and 121 cockatoos. Having been passed over for a major position at the Conservatoire, ignored and humiliated (as he saw it) he withdrew from the public, still yearning for official recognition. One anecdote illustrates his character. Towards the end of his life a delegation of officials finally called upon him one afternoon, just after he had finished lunch, to invest him with some award or other. He met them at the door saying, ‘Messieurs, à cette heure, moi, je digère’ (‘Gentlemen, at this hour I digest’). The delegation departed and that was the end of Alkan’s chances for a decoration. Today it’s the nature of his ultimate demise that evokes a reaction at the mention of his name, rather than any of his music, for he suffered one of musical history’s most unusual deaths. He was crushed by a bookcase (although the legend of him having reached up for the Talmud – which miraculously remained clutched in his hand – may be a romanticized version of the event).

With more of Alkan’s music available now than ever before, the list of extraordinary works, of revelatory piano compositions, grows yearly. No sneering musicologist can deny the epic grandeur (in writing and conception) of the Twelve Études in all the minor keys, Op 39, of which Nos 4, 5, 6 and 7 comprise the Symphony for solo piano, and Nos 8, 9 and 10 form the Concerto for solo piano (the recording of which by Mr Hamelin being, in this writer’s opinion, one of the single most astonishing exhibitions of virtuoso pianism ever captured on disc). The études are among the masterpieces of the piano’s literature and inspired Hans von Bülow’s famous description of Alkan as ‘the Berlioz of the piano’. Then there’s the Grande Sonate, Op 33, subtitled ‘Les quatre âges’, the futuristic La chanson de la folle au bord de la mer and Le Tambour bat aux champs, the Trois grandes Études, Op 76, the Grand duo concertant, Op 21, the impromptu on Luther’s Un fort rempart est notre Dieu, Op 69 … the contents of his secret treasure chest are slowly emerging to intrigue and delight.

So what of the present two discoveries? First the title, ‘Concerto da camera’, first used for Baroque music. Just as there were two types of sonata (‘sonata da chiesa’, a church sonata with abstract movements, and ‘sonata da camera’, a chamber sonata with dance-style movements), so there were two types of concerto. Here, a more apposite description would be ‘Concertino’, for the two by Alkan contain no dance music and both take the form of a short concerto.

Scored for piano and strings, the Concerto da camera in C sharp minor, Op 10 No 2, was composed in 1833 (when Alkan was only twenty) during a visit to England. It remained a lifelong favourite. It is dedicated to the minor composer and pianist Henry Field, Bath-born and -bred (1797–1848), who gave the first performance there on 11 April 1834 (the Bath and Cheltenham Gazette reviewed it as ‘especially delightful for the novelty of its style and technique’). Field must have been no mean player to cope with some of the novel and challenging keyboard acrobatics, especially the final section of its simple A–B–A structure which incorporates lightning-fast arpeggios and jumps that put it way beyond the gentleman amateur. This is not Alkan at full stretch (as in the Twelve Études) but, despite the obvious limitations and influences in the work, clearly he already knows that he has a voice of his own.

The Concerto da camera in A minor, Op 10 No 1, premiered by Alkan in Paris in 1832, has never been recorded before, either as a piano solo, or (as here) in its original form. It is doubtful whether it’s been played more than a handful of times since its composition; the existence of a full set of parts was only discovered in the 1980s. This is a more ambitious ‘concertino’ than its successor, again in one movement though in three distinct sections. It is scored for strings, double woodwind (with two extra bassoons), four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and timpani. Throughout, one is reminded of other composers but never convinced. Here is a Mendelssohnian theme, there a Chopinesque modulation, here some awkward Weber-like passagework. But no, it is a different, independent thinker throughout, too masculine for Chopin, too sharp-cornered for Mendelssohn. Any pianist tackling this must have nimble fingers and (in all three sections) good octaves and sparkling repeated notes. The work is dedicated to Alkan’s teacher Joseph Zimmerman (1785–1853), who himself was a pupil of Cherubini.

The two Alkan concertos, for all their attractions, are still minor works. So are the Henselt variations. The F minor Concerto is a major piano composition. But whatever their various emotional, musical and structural merits and limitations, in the end one simply has to ask: ‘Are they effective and well-wrought? Do they stand up to repeated hearing? Are they worth reviving?’ The answer to all three questions surely is ‘yes’, and one must add: ‘But why has it taken until now before most of us have had a chance to hear them?’ Hyperion

Adolph von Henselt (1814-1889)

Piano Concerto in F minor Op 16 [29'44]

Variations de concert Op 11 [17'47]

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888)

Concerto da camera in C sharp minor Op 10 No 2 [7'30]

Concerto da camera in A minor Op 10 No 1 [14'14]

Credits :

Conductor – Martyn Brabbins

Leader [Orchestra] – Bernard Docherty

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

KORNGOLD : Piano Concerto In C Sharp For The Left Hand, Op 17 ♦ MARX : Romantisches Klavierkonzert (First Recording) (Marc-André Hamelin · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra · Osmo Vänskä) (1998) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 18 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The Korngold left-hand concerto was written (like that of Ravel) for Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein who had lost his right arm during the First World War. It is Korngold at his most experimental and features a very large and colourful orchestra, and a particularly demanding (and awkward) piano part. Hyperion

Joseph Marx (1882-1964)

Romantisches Klavierkonzert in E major [36'30]

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957)

Piano Concerto for the left hand in C sharp Op 17 [27'37]

Credits :

Conductor – Osmo Vänskä

Leader – Iain King

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

15.1.22

BUSONI : Piano Concerto Op XXXIX (Marc-André Hamelin · City Of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra · Sir Mark Elder) (1999) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 22 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

The Busoni concerto, with its five movements, choral finale and a length of over 70 minutes, is surely the most grandiose ever written. But this is no over-ambitious monster; Busoni was one of the greatest pianists the world has known, but he was also a great intellectual with very strong views on art and culture. This work is the masterpiece of his middle years, more of a symphony in the breadth and scope of its ideas, but at the same time almost casually requiring the most formidable technical ability from the soloist. There is no doubt that this is one of music's major neglected masterpieces.

Marc-André Hamelin needs no introduction as a champion of the greatest challenges in the piano literature. Here he is joined by Mark Elder who has a particular reputation as a Busoni conductor. He conducted this work with Peter Donohoe in their famed Proms performance of 1988 and he has also conducted Busoni's rarely performed magnum opus 'Doctor Faust' at ENO. Hyperion

Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

Piano Concerto in C major Op 39

Credits :

Conductor – Mark Elder

Leader [Of Orchestra] – Jacqueline Hartley

Orchestra – City Of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

14.1.22

RUBINSTEIN : Piano Concerto No 4 In D Minor ♦ SCHARWENKA : Piano Concerto No 1 In B Flat Major (Marc-André Hamelin · BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra • Michael Stern) (2005) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 38 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Franz Xaver Scharwenka (1850-1924)

Piano Concerto No 1 in B flat minor Op 32 [27'55]

Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894)

Piano Concerto No 4 in D minor Op 70 [31'16]

Credits :

Conductor – Michael Stern

Leader – Bernard Docherty

Orchestra – BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

13.1.22

REGER : Piano Concerto In F Minor, Op 114 ♦ STRAUSS : Burleske (Marc-André Hamelin · Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin · Ilan Volkov) (2011) Serie The Romantic Piano Concerto – 53 | FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Max Reger (1873-1916)

Piano Concerto In F Minor Op 114 (37:23)

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Burleske In D Minor 19:25

Credits :

Conductor – Ilan Volkov

Orchestra – Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin

Piano – Marc-André Hamelin

7.1.22

29.12.20

STRAVINSKY : The Rite of Spring; Concerto for Two Pianos; Circus Polka; Tango; Madrid (Hamelin-Andsnes) (2018) FLAC (image+.cue), lossless

Since the centenary of Igor Stravinsky's Le Sacre du printemps in 2013, recordings of the version for two pianos have increased, and many virtuoso pianists have taken up the challenge that Stravinsky's colorful transcription presents. For this 2018 release on Hyperion, Marc-André Hamelin and Leif Ove Andsnes team up to give one of the most brilliant and precise readings of the work, and followed it with a muscular rendition of the neoclassical Concerto for two solo pianos (1932-35), and delightful interpretations of Madrid from the Four Etudes (1917, revised in 1928), the Tango (1940), and the Circus Polka (1941-42), the last three pieces in arrangements by different hands. The intricate textures, complex rhythms, and explosive violence of Le Sacre du printemps are clearly communicated in this fascinating performance, and Hamelin and Andsnes successfully imitate the original orchestral sonorities and tone colors through controlled touch, varied accentuation, and carefully shaded dynamics. Listeners who are well acquainted with the orchestral version will find that Hamelin and Andsnes have come quite close to duplicating many of Stravinsky's effects, most powerfully in the Glorification of the Chosen One and the closing Sacrificial Dance, though with great subtlety in the softer sections. The Concerto is a bit drier in coloration and more involved with intricate counterpoint than evocative timbres, but the pianists play it with sufficient energy, clarity, and wit to hold the listener's attention. The final selections serve as encores, and Hamelin and Andsnes take the opportunity to have a little fun, which is welcome after the intensity of Le Sacre du printemps and the fairly cerebral Concerto. Highly recommended. by Blair Sanderson

Since the centenary of Igor Stravinsky's Le Sacre du printemps in 2013, recordings of the version for two pianos have increased, and many virtuoso pianists have taken up the challenge that Stravinsky's colorful transcription presents. For this 2018 release on Hyperion, Marc-André Hamelin and Leif Ove Andsnes team up to give one of the most brilliant and precise readings of the work, and followed it with a muscular rendition of the neoclassical Concerto for two solo pianos (1932-35), and delightful interpretations of Madrid from the Four Etudes (1917, revised in 1928), the Tango (1940), and the Circus Polka (1941-42), the last three pieces in arrangements by different hands. The intricate textures, complex rhythms, and explosive violence of Le Sacre du printemps are clearly communicated in this fascinating performance, and Hamelin and Andsnes successfully imitate the original orchestral sonorities and tone colors through controlled touch, varied accentuation, and carefully shaded dynamics. Listeners who are well acquainted with the orchestral version will find that Hamelin and Andsnes have come quite close to duplicating many of Stravinsky's effects, most powerfully in the Glorification of the Chosen One and the closing Sacrificial Dance, though with great subtlety in the softer sections. The Concerto is a bit drier in coloration and more involved with intricate counterpoint than evocative timbres, but the pianists play it with sufficient energy, clarity, and wit to hold the listener's attention. The final selections serve as encores, and Hamelin and Andsnes take the opportunity to have a little fun, which is welcome after the intensity of Le Sacre du printemps and the fairly cerebral Concerto. Highly recommended. by Blair Sanderson

+ last month

THE HOKUM BOYS & BOB ROBINSON — The Complete Recorded Works 1935-1937 In Chronological Order | DOCD-5237 | RM | FLAC (tracks), lossless

Although hokum had its heyday from 1928-31, the name of the Hokum Boys was revived for some recording dates during the years 1935-37. This C...

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)