In 2000, Editio Musica Budapest published a small volume, splendidly edited by Dr Mária Eckhardt, of Albumblätter. The following note is gratefully derived from information in the excellent critical apparatus to that volume. It was probably Liszt himself who gave a bound music-manuscript album to the ten-year-old Princess Marie zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (1837-1920) at the end of August 1847, at the conclusion of his second visit to Woronince, whence he had been invited by the woman who was to dominate much of the rest of his life: Marie’s mother, the Princess Carolyne (1819-1887). This album contains musical autographs and original pieces by some 44 musicians, but the first four entries in the book are a set of pieces on Polish themes by Liszt, dating from some time after 30 August 1847. Another piece by Liszt, dating from March of the same year, and dedicated to Carolyne’s mother, Madame Iwanowska, is pasted into the album on the empty first page. The album was known about, but had passed into private hands and consequent obscurity until the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv in Weimar managed to buy it when it finally reappeared at auction in 1999.

The pasted-in sheet contains the Album Leaf – Freudvoll und leidvoll. Untitled in the manuscript, the music is clearly based on the song from Goethe’s Egmont that Liszt had composed in 1844. The four pieces following – Lilie, Hryã, Mazurek and Krakowiak – are all based on Polish folk melodies – two songs and two dances. Liszt had notated quite a number of these tunes in his 1845-1847 sketchbook (N5 in the Weimar archive, and some detached sheets in Z18, copies of which are in the present writer’s collection) and used the Hryã song in the first piece of the Glanes de Woronince (recorded in volume 27 of the Hyperion Liszt series). All of these little pieces must have made excellent gifts for a gifted child.

In 1840, and again in 1846, Liszt travelled within Hungary, listening to the music of the gypsy bands and notating many of their themes. Some of these themes were compositions by minor composers of the day, who deliberately produced short pieces for the bands’ use; others were actually Hungarian folksongs. The distinction was as blurred for Liszt as it remains to present-day players in Hungarian orchestras of traditional instruments. By 1848, Liszt had composed twenty-two piano pieces based on such themes, and eighteen of them were published in the 1840s under the title Magyar Dalok – Ungarische National-Melodien and Ungarische Rhapsodien – Magyar Rapszódiák – Rapsodies hongroises (‘Hungarian Songs and Rhapsodies’, usually referred to by their Hungarian title to avoid confusion). By 1851, Liszt had embarked upon a new series of fifteen works, to which four more were later added: the famous Rapsodies hongroises (Hungarian Rhapsodies). Numbers III-XV of the second set were entirely constructed from material from the first set. In between, Liszt embarked on a project that he left unfinished: the production of a series of works of moderate difficulty derived from the Magyar Dalok and Magyar Rapszódiák, under the title Zigeuner-Epos (‘Epic story of the gypsies’).

The manuscript of Zigeuner-Epos, which forms pages 36 to 62 (as numbered by archivist Felix Raabe) of the sketchbook N7 in the Weimar archive, has been neglected as an apparently incomplete set of sketches, and is not mentioned in the catalogues (save that of Michael Short and the present writer, the worklist from which is published by Rugginenti). It is demonstrable, however, that Liszt wrote in a kind of musical shorthand (with many bars simply containing numbers) for which it is necessary to read the published score of the Magyar Dalok and Magyar Rapszódiák in tandem with the manuscript to derive the full texts of the new collection. In this way, eleven pieces can be retrieved. (There is no surviving manuscript source for the printed Magyar Dalok and Magyar Rapszódiák, so we have referred to the original editions by Haslinger (1840, 1843 and 1847) for the passages retained in the Zigeuner-Epos.) We do not know why Liszt abandoned this intermediate set; the manuscript breaks off at bar 109 of number 11, although the rest of the piece can be surmised from the work on which it is based. Liszt returned to the manuscript on at least one occasion to sketch a plan for an orchestral version of number 6. Of course, all of these later markings in red crayon were not taken into account in the preparation of the score of the original piano piece.

The manuscript bears a title, a signature and a subtitle in Liszt’s hand, but no date. (We may presume that the earliest likely date is 1847, when the first series of pieces was completed; and the latest possible date is probably 1851, when the second series was already begun.) It reads: ‘Zigeuner-Epos / FLiszt / populäre Ausgabe / in erleichterten Spielart [this last word is a conjecture from an illegible scrawl] / den / Ungarische Melodien und Rapsodien’ (‘Epic story of the gypsies / FLiszt / popular edition / in a simplified performing manner / of the / Hungarian Songs and Rhapsodies’). Thus it is clear that, at the outset at any rate, Liszt intended to publish this set.

The manuscript continues: ‘Nn 1 und 2 bleiben’ (‘Nos 1 and 2 remain’). Therefore we have retained the short numbers 1 and 2 from the Magyar Dalok and Magyar Rapszódiák unchanged. Then we find: ‘Nr 3 – Seite 6 – Variant’ (‘No 3 – page 6 – variant’). This refers to the following bars of music, which are to be substituted from bar 17 to the end of number 3. In keeping with the stated intention, Liszt’s simpler alternative text of the first eight bars is preferred. The next item in the MS is numbered 6, so it may be assumed that the short numbers 4 and 5 are likewise to be retained (again, Liszt’s simpler alternative text for two short passages in the left hand of number 4 has been preferred).

Number 6 is a conflation by Liszt of material from numbers 6 and 12 of the Magyar Dalok and Magyar Rapszódiák. The whole piece is written out in full. The MS then reads: ‘Rákóczi Nr 7’ and a space is left. Here Liszt clearly requires the insertion of the easier of the two versions of the Rákóczi-Marsch which appear in the Magyar Dalok and Magyar Rapszódiák (number 13a), and so we perform it here.

The rest of the manuscript contains numbers 8, 9, 10 and 11, which correspond to Numbers 10, 7, 8 and 9 respectively of the Magyar Dalok and Magyar Rapszódiák. Liszt only writes the (many) passages that are to be altered, and the remaining bars are marked to be taken over from the published versions.

We have no way of knowing how many pieces were to be included in this set. A scribbled note above number 8 indicates a key scheme for an orchestral version, but it does not tie in with the pieces as they remain. However, another of the themes from the Magyar Dalok (from No 11), also known to us from its appearance in Rapsodie hongroise No VI, was issued much later in a version prepared for Francis Planté, entitled Célèbre mélodie hongroise, with a new ending, and a few little alterations en route. This piece, too, is not known to the old catalogues, and we offer it here as a little encore.

As we have seen, Liszt spent much time preparing the Troisième année de pèlerinage (recorded in Volume 12), and all but one of the pieces exist in earlier versions (see Volumes 55 and 56). The version of Angelus! offered here is really the first clean copy of the draft version, and the manuscript is dated 2 October, 1877, Villa d’Este, and bears a dedication to Liszt’s granddaughter Daniela von Bülow. The intermediate version of Sunt lacrymae rerum was made by Liszt altering and pasting over various passages in a fair copy of the first version. It is strikingly different from the original and yet quite at variance with the final published text. So, too, does the first version of Sursum corda strike out in quite a different direction from its famous successor, and it remains fascinating to see Liszt’s imagination at work. It is not that the later versions are necessarily better or worse, but that a completely different musical journey is often made on the basis of the same material.

Thanks to the splendid detective work of Professoressa Rossana Dalmonte (Istituto Liszt, Bologna), Liszt scholars have had to take another look at the provenance and history of the most famous of Liszt’s late compositions: La lugubre gondola. We can now establish a clear chronology of the piece, and the present version transpires to be the original conception, composed while Liszt was staying with Wagner at the Palazzo Vendramin on the Grand Canal in Venice in December 1882, a piece which Liszt later described as having been written as if under a premonition of Wagner’s death and funeral (Wagner died at the Vendramin in March 1883). The only version of the work published during Liszt’s lifetime is a revision of this manuscript issued by Fritzsch in 1885, known since 1927 as La lugubre gondola II, because in that year Breitkopf & Härtel published it alongside another work with the same title, known as La lugubre gondola I – an erroneous order of chronology. In August 1998, at the Benedetto Marcello Conservatorium in Venice, Rossana Dalmonte found two autograph manuscripts of La lugubre gondola (cf A and B below) which permit the establishment with reasonable precision of the following chronology: A 1882, December: Die Trauer-Gondel – La Lugubre Gondola, for pianoforte, in 44 [first version], the piece in the present recording (S199a); B 1883, January: La Lugubre Gondola, for pianoforte, in 44 [second version], the text which, with minimal alteration, constituted the basis of the 1885 edition (S200/2); C circa 1883: La lugubre gondola, transcription for violin or cello and piano from the version B above (S134), with twenty bars added in place of the last three at a later moment (but probably before the publication of B, since it lacks the final changes to the original text); D circa 1884–5: La lugubre gondola, for pianoforte in 68, the so-called La lugubre gondola I. This is really a new composition, but clearly derived from the material of B (S200/1). The Venice manuscripts were published for the first time in 2002 by Rugginenti in Milan, under the editorship of Mario Angiolelli. The well-known versions of the piece are available on volume 11 of the Hyperion Liszt Series.

The three tiny Album Leaves are not mentioned in earlier catalogues. The first turned up in a Sotheby’s auction catalogue in 2000, where it was listed as dating from 1844. However, since the piece was printed in its entirety in the catalogue, it is the work of an instant to read in Liszt’s unambiguous hand ‘3 avril 1828’. The fragment of ten bars’ Allegro vivace quasi presto was also described in the catalogue: ‘This quotation has not been identified among the known works of Liszt’. But the truth is more exciting. Although written as an album leaf, and with ‘etc etc’ written in the last bar, the actual music amounts to the earliest known sketch relating to the Second Piano Concerto, whose final form dates from more than thirty years later. The early drafts of the concerto contain the music of the album leaf, but in B flat minor, and the figuration remains unchanged. By the final version of the concerto, the material has been much transformed, but the harmonic and melodic outline is the same (see the Allegro agitato assai at bar 108 of the concerto).

The Weimar archive contains a folder of miscellaneous sketches and fragments under the shelf-mark Z12, whence comes the undated and otherwise unidentified Friska. The present writer is of the opinion that the page dates from the same period as Liszt’s other Hungarian pieces from the 1840s.

The tiny chord sequence of the last of these album leaves is a transposition of the progression with the whole-tone scale in the bass at the end of the Dante Symphony (completed in 1856), but the fragment of paper on which it is written (the signed autograph is held at Boston University) is otherwise without date or place. Leslie Howard © 2002

All Tracks & Credits

28.1.22

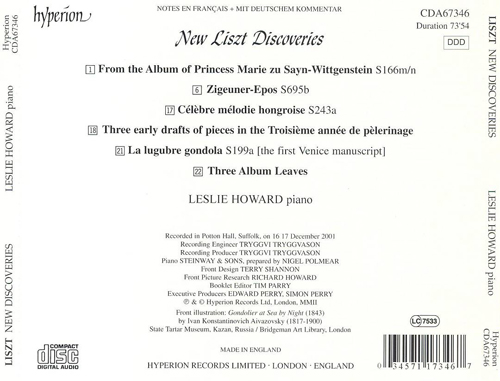

FRANZ LISZT : New Liszt Discoveries (Leslie Howard) (2001) FLAC (tracks+.cue), lossless

Assinar:

Postar comentários (Atom)

+ last month

JOSEPH GABRIEL RHEINBERGER : Organ Works • 1 (Wolfgang Rübsam) (2001) The Organ Encyclopedia Series | Two Version | WV (image+.tracks+.cue), lossless

Organist, conductor, composer and teacher, Rheinberger was born in Vaduz, Liechtenstein, where he held his first appointment as organist. He...

.jpg)

.jpg)

https://nitro.download/view/6391862BB7A1F2D/Franz_Liszt_-_New_Liszt_Discoveries.rar

ResponderExcluir